From state-owned photo studios to personal digital SLRs, check out the history of modern Chinese photo-taking

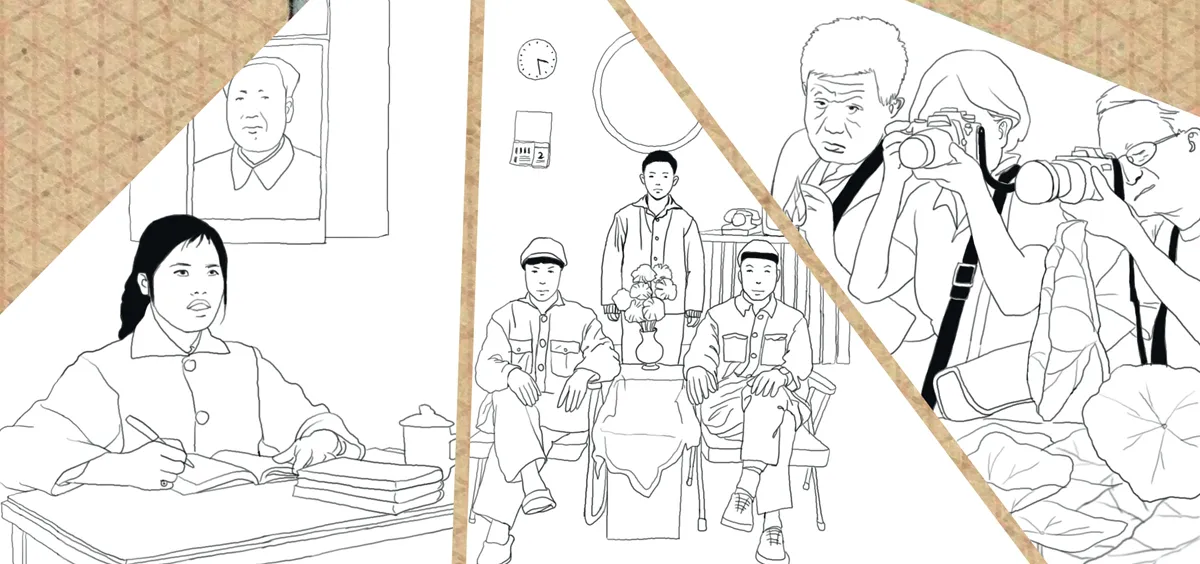

In 1978, Wu Haijun made a living taking photos of villagers in Sichuan Province with his Pearl River twin-lens reflex camera. Business was good; in rural China, a camera was a rare thing. Families, many of whom had never been photographed before, put on their best clothes for the occasion. For each photo, Wu charged 0.64RMB. Wherever he was, he would always convert his own bedroom into a studio; he developed the photos in bed after it got dark, washed them in basins and flipped them with chopsticks.

Wu didn’t want to work in a city. In fact, he couldn’t. The market was dominated by well-equipped photo studios, most of which were state-owned (and would be until the late 1990s). Wu couldn’t compete with their plastic fruit and flower arrangements, their picturesque backdrops of the Great Wall or a forest in autumn. After all, city dwellers took these things seriously on the few occasions they actually went to a photo studio. It was a sort of ritual, something you did only on special occasions such as birthdays, graduations and weddings.

By today’s standards, the equipment that set these studios apart seems almost medieval. The lighting was dependent on bulbs that were at most 200W, and light meters and remote shutter cords were rare. Touching up photos wasn’t a matter of just two or three clicks in Photoshop, it was an art.

“In order to smooth out a picture and wipe out dots and scratches, we needed to retouch it with pencils, knives, brushes and ink,” Wu Chuanbin, a photographer in Ziyang, Sichuan Province recalled. “Those tools were our primitive Photoshop. To become good at retouching photos, an apprentice needed to be trained for over a year.”

In the late 80s and early 90s, black-and-white close-ups, enlarged to 24-40 inches in length, became popular. Wu often needed to work late into the night to develop this type of photo, what he called “vintage Hollywood.” But the work paid off; the outcome was a portrait with an inherent charm that modern photo studios, even with their advanced equipment, have a hard time replicating.

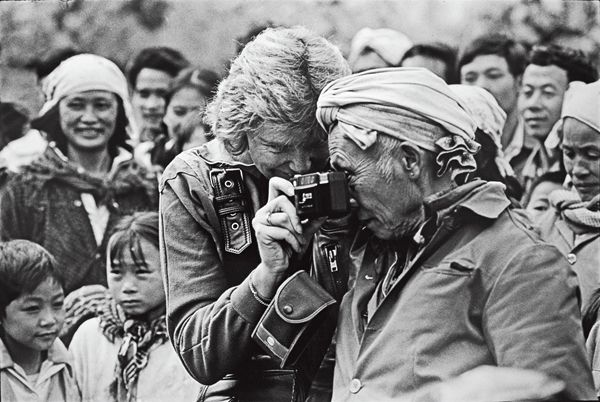

A German tourist lets an elderly Yao villager from Ruyuan County, Guangdong Province, peer through her camera lense for the first time in 1986 (Fotoe)

“When my son was 100 days old in 2011, I took him to a modern photo studio for a birthday shoot, but it was a disappointment,” 34-year-old Meng Hui complained. “There was no background lighting. They went overboard with the Photoshop, making the photo look two-dimensional. I took out my own photo from when I was a child and sighed. My 100-day photo was so cute that the photo studio enlarged it and put it in the window. My grandpa was so proud.”

After this, Meng became a client at an old-style photo studio called China Photo Studio (中国照相馆) in Jiaodaokou, Beijing. “They take better photos and they still use the old, stiff photo paper we used decades ago. They even cut the paper rims like we used to. But still, it’s not exactly the same. Maybe it’s because attitudes have changed and people aren’t as excited or formal when going to a photo studio.”

In the 1980s, international brands like Canon, Nikon or Kodak didn’t exist within China, we only had domestic brands like Seagull (海鸥), Phoenix (凤凰) and Huaxia (华夏). However, even these brands were a luxury. In the late 1970s Seagull was the most popular model and was director Zhang Yimou’s (张艺谋) first camera. His old time friend Lei Peiyun (雷佩云) recalled in an interview with the Southern Metropolis Weekly (《南都周刊》), “At that time our salary was 30.2 RMB. He (Yimou) saved a lot of money by being thrifty, but instead of buying clothes or a bicycle, he bought a Seagull camera.”

Shang Minjie, a Luoyang-based photographer, has been publishing photos of the city’s threatened Old Town online as a part of his effort to preserve the area. He bought his first camera in 1990; the funding for it was provided by his parents. However, he soon found that his monthly salary as a soldier didn’t cover the costs associated with operating the camera. A roll of Fuji film cost 20RMB, which was four times his salary. Unwilling to give up, Shang went on a photography training course so that he could be “theoretically prepared to use [his] camera before wasting any rolls.”

The dawn of the compact camera in the 1990s made photography far more accessible, so much so that the compact camera came to be known as “the fool’s camera” (傻瓜相机). A rise in tourism in the 90s meant that these camera-toting “fools” came to redefine what it meant to travel. A trip was meaningless unless you posed for a shot at every tourist site. A popular saying at the time was, “I sleep when I’m on the bus, take photos when I get off, and remember nothing when I get home.” (上车睡觉,下车照相,回来什么都不知道。)

Chating Park in Fuzhou, Fujian Province saw blossoming flowers in June 2011, attracting hoardes of budding photographers to capture the rare moment (CFP)

“When my family travels together, there seems to be only two reasons for the trip—shopping and taking photos,” says Beike, a 24-year-old translator, who is continually perplexed by the way her parents travel. In photo after photo, they stand centered in the frame, smiling at the camera, as if the world is their photo studio.

As the tourism industry matured, with guided tours giving way to DIY travel, low price digital single-lens reflex cameras(DSRL, 单反) hit the market, catering to tourists for whom a compact camera would no longer suffice. Canon was the first to respond to this demand with a low-price DSLR in 2004, soon to be followed by Nikon. The competition for quality and affordability encouraged sales of DSLRs in China, and the market grew exponentially. In 2006, 250,000 DSLRs were sold in China. That was triple the number sold in 2004. In 2007, the number grew by another 50 percent.

But it’s hard to stop at a budget-friendly DSLR, and for many middle class Chinese, the hobby quickly becomes an obsession—and a pricey one, at that. One of the most prevalent jokes about cameras goes: “Drugs ruin your life, but SLRs will ruin the lives of three generations” (吸毒毁一生, 单反穷三代). Another version of the saying warns, “If you want a man to go bankrupt, give him an SLR camera as a gift” (想让男人破产,送他一台单反). Convinced that a steady stream of investment is the only way to realize their full potential, photographers constantly upgrade to new lenses and models, seemingly without end.

But the ill-effects don’t stop at a lighter wallet; relations with fellow traveling companions can also be tested when photographers stall for the perfect shot. Zhu Yaning, a 42-year-o ld backpacker who often carpooled with follow snappers on her way to remote Tibetan villages, complains, “Usually I enjoy traveling with creative people, but most of the photographers I’ve traveled with are people who would stay for an hour on a hilltop because a National Geography photographer once took a photo there.”

Huo Caichi, a retiree in his 60s who carries three cameras with him when he travels, feels differently.

“Those travelers who do not use cameras do not understand us. How can’t they see that the sunlight is too stiff, and that I need to wait for two hours for it to soften a bit?”