Struggling against sexist notions, married women try to hold on to their land rights

By day, 35-year-old Long Yuting is a stay-at-home mother for her two children. But after they fall asleep at night, she becomes a legal expert—reading law books and writing civil complaints to get back her dividends, farmland, and other benefits that her village committee has denied her for almost 10 years, ever since they heard she’d gotten married.

Born in a village in Zhaoqing in the southeastern Guangdong province in 1987, Long, like all her neighbors, had been entitled to a piece of the village’s farmland and had paid agricultural tax on it every year. In 1996, the village collective transformed the lands into fishponds operated by a third party, which yield an annual dividend of around 700 yuan per villager (now increased to 6,500 yuan), which Long was entitled to collect along with her parents and brothers.

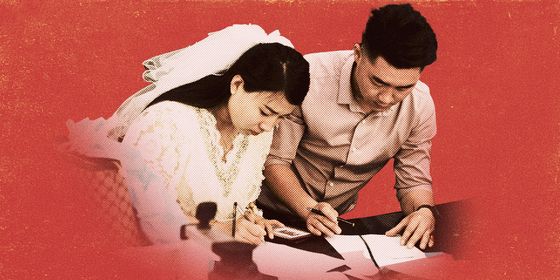

In 2011, Long married a man from another village. When she divorced him two years later, cadres from her own village belatedly became aware of the marriage and decided to strip her of benefits from the village collective. They even reclaimed some dividends they had already paid in the previous two years to rectify their “mistake”—because a married woman, they argue, is not entitled to any further benefits from her birth village.

But this is simply not true under Chinese law—Long had become one of the millions of so-called chujianü (出嫁女, “married-out women”) in rural China who’ve lost their legal rights from their village after marriage, and one of hundreds of thousands to have taken legal action, sometimes for years, to get back what they are owed. Yet conservative notions, combined with the increasing value of land and a lack of clear rules for enforcing land rights in rural areas, often bring their fights to a dead end.

In the early 1980s, China enacted reforms to replace collective farming. Land was still collectively owned by residents who held a household registration (hukou) in the village, but they were given some autonomy over how to use the plots allocated to them according to the size of the household. Today, the rural collective holds assemblies to decide matters regarding land allocation and land-use, and the collective can contract their land to outsiders with agreement from two-thirds of the members.

Legally, a woman with a hukou in the village is automatically a member of the collective and entitled to the same rights as any other villager. However, traditional notions such as “marrying out a daughter is like tossing out a basin of water” hold strong in parts of Chinese society, especially in rural areas. It is widely believed that a woman belongs to her husband’s family after marriage. Regardless of the law, many village collectives consider “married-out women” like Long to have severed ties with their birth village. In many cases, their farmland and residential plots, and other benefits such as rural cooperative medical insurance and voting rights, will be taken back by the village.

For Land’s Sake: The Women Fighting to Keep Hold of Their Rural Land is a story from our issue, “Promised Land.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.