From helping humanity grow food to becoming good luck charms for flood control, stories about cattle are as old as Chinese civilization itself

Happy Year of the Ox, or 牛 (niú) ! Ranked the second in the 12 zodiac animals, the Ox symbolizes diligence and prosperity.

In contrast with the passing Year of the Rat or 鼠 (shǔ), when some struggled to find rat-related New Year’s greetings, we have no shortage this year: we wish you 牛气冲天 (niú qì chōng tiān, “auspicious air rises above Heaven”), 牛运亨通 (niú yùn hēng tōng, “great luck in all endeavors”), and 牛劲百倍 (niú jìn bǎi bèi, “be robust like an ox”)!

Traditionally, the ox is considered to be an animal that works hard and makes no complaints. In the legendary race held by the Jade Emperor to decide the order of the zodiac animals, the Ox was in the lead the whole time, but lost to the Rat, who took a free ride on the Ox’s back and leapt forward when they were about to reach the finish line.

Modern oxen, on the other hand, would likely contest such a result. In oral Chinese, niu suggests an air of arrogance, and can be used to describe people, as in 牛人 (niúrén, “ox man,” a very capable person ); or a rising stock market, or 牛市 (niúshì, “ox market”). It can also simply be a word of praise you can throw at anything and anyone: “牛 (niú, awesome)!”

The Chinese character 牛 refers to all kinds of bovine: from the 黄牛 (huángniú, yellow cattle), the most common cattle in northern China, to the 水牛 (shuǐniú, water buffalo) native to China’s watery south, to the 牦牛 (máoniú, yak) local to China’s southwestern plateau. This all-encompassing character can also refer to cattle of all ages and sex.

It used to be commonly believed that modern cattle were first domesticated around 10,000 years ago in the Middle East, based on archeological and genetic evidence. However, a new study by Chinese and European scientists in 2013 revealed that Neolithic peoples in what is now northeastern China may have started cattle domestication over a century earlier.

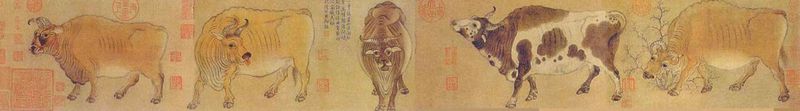

Five Oxen is a classic Chinese painting by Han Huang (韩滉) in the Tang dynasty (Wikimedia Commons)

Due to their long years as companion to ancient humans, and their indispensable role as draft animals in an agricultural society, cattle have left numerous marks in Chinese history, culture, and language. Various myths and legends depict the relationship between cattle and agriculture. According to one legend, long ago, cattle took pity on the harsh lives of humanity, and stole magical seeds from the barn of the Jade Emperor for humans to grow. As a punishment, the heavenly ruler sent cattle to serve humans. This is why cattle are also referred to as 仁畜 (rénchù, benevolent livestock).

In another legend, the ox was supposed to pass a message to the humans from the Jade Emperor, ordering them to “freshen up three times and eat once a day.” The ox miscommunicated the message as “freshen up once, and eat three times a day.” Since there wasn’t not enough food to sustain this lifestyle, the Jade Emperor sent the ox to help the humans with agriculture.

Cattle also play a role in the myth of the founding of Chinese civilization. In pre-historic times, Huangdi (黄帝), the Yellow Emperor, fought over the control of central China with his arch-enemy Chiyou (蚩尤), who is described as an ox-headed warrior. Huangdi won the battle and went on to father the Han ethnicity. Chiyou migrated north and became the ancestor of the Miao, an ethnic group based in southern China.

Historians suspect that the myth contains grains of truth, the ox-headed god may be based on the ox totem used by Chiyou’s tribe. One piece of evidence for this theory is that buffalo worship is still very prominent in Miao culture today. The Miao people continue to use ox pattern in their traditional garments and decorations, and practice rituals like buffalo fighting on traditional holidays.

Miao people in Anshun, Guizhou province, bathe and parade a buffalo as part of the Siyueba Festival on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month (VCG)

Traditionally, cattle symbolized stability and safety. Legend has it that Yu the Great, the mythical leader credited with treating floods in ancient China, would cast iron buffalo statues and throw them into the rivers and lakes to keep disaster at bay. This practice later changed into placing iron buffalo statues near bodies of water for blessing. One can still find many such statues by rivers and lakes across China today.

Since at least the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE), cattle have become widely domesticated, along with the horse, sheep, chicken, pig, and dog. Together, they were referred to as the “six domestic animals (六畜)” of a Chinese household.

As in many cultures around the world, cattle were involved in important political and spiritual ceremonies in ancient China, often conducted by kings and emperors. The Chinese term for sacrifice, 牺牲 (xīshēng), consists of two characters with the ox radical 牜; the latter character, 牲, refers to cattle of a solid color.

In the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE) when semi-independent states formed alliances and contended for dominance of China, a key ritual for solidifying a military alliance called for the leader of each state to smear animal blood on their lips and swear an oath together. The chief of ceremonies was responsible for cutting the ear of an ox to get the blood. Therefore, the term 执牛耳 (zhí niúěr), or “holding a cattle ear,” refers to someone with dominant power.

Apart from its importance to rituals, the ox’s role in agriculture made slaughtering cattle a serious offense in ancient China. In the Southern and Northern Dynasties period (420 – 589), Xie Xuan (谢谖), a minister of the Eastern Jin state, was banished simply because his family slaughtered an ox. During the Tang (618 – 907) and Song (960 – 1279) dynasties, civilians could only eat the meat of farm cattle if the animal died a natural death.

Because cattle are used primarily to plow the fields, they came to be associated with spring. On Lichun (立春, spring begins), the day that marks the official beginning of spring in the Chinese calendar (late January or early February), there is a folk ritual called “whipping the spring cattle (打春牛, dǎ chūnniú).” The cattle that is whipped is actually a clay or papier-maché sculpture. The ritual is accompanied by song and dance, and it is a celebration of spring as well as a prayer for good harvests to come.

A folk opera performer dressed up to perform the “whipping spring cattle” ritual in Yancheng, Jiangsu province (VCG)

Cattle have been praised by poets and writers throughout history for their diligent labor alongside humans. A poem titled “The Ill Cattle,” composed by Song dynasty minister and poet, Li Gang (李纲) illustrated the sentiment: “Plowing thousands of mu of lands with grains filling thousands of barns/ Who takes pity of the exhausted cattle?/ To feed the masses, the cattle now lie tired and ill in the sunset with no regrets.” The 20th century writer and literary critic Lu Xun (鲁迅) also compared himself to cattle serving the public with his writing, stating “With head bowed, I serve the children like a willing ox (俯首甘为孺子牛, fǔ shǒu gān wéi rú zǐ niú, head-bowed).”

Suffice to say, tales about cattle have been around as long as human civilization itself. In the spirit of the benevolent, diligent, and all-powerful cattle, we wish you a happy Year of the Ox!

Cover image by VCG