How the “post-90s generation” has grown up in the new millennium

How many years of avocado toast abstinence does it take to buy an apartment in Shanghai? In a 60 Minutes interview last May, Australian property tycoon Tim Gurner opined that middle-class indulgences like artisanal snacks and lattes were all that stood between today’s young adults and their first home purchase.

As the multimillionaire’s tirade birthed a million memes, a Twitter user quickly figured out that daily avo-toast avoidance would earn him a “bad house” in Los Angeles in 642 years. But while avocado-based dishes are only beginning to enter Chinese consumers’ orbits—imports of the fruit grew 16,000 percent between 2012-2016—millennials have long been feeling the squeeze of stagnating incomes and rising living expenses. In 20 of China’s major cities, the housing price-to-income ratio has risen well above 10:1. Beijing (26.08), Shanghai (25.48), Shenzhen (32.44), Hangzhou (13.43), and Nanjing (12.36) are among the least affordable cities in the world.

Dai Weijie, a Shanghai college graduate born in 1993, estimates that at his current salary, he needs to work 500 months to buy an apartment in his home city—that’s 41 years, half a lifetime. Like many of his peers, Dai worked tirelessly in school, landed a promising white-collar job after graduation—finance in his case—and has parents who saved up his whole life to help him afford a home. But even he isn’t optimistic. “After those 500 months,” he says, “housing prices are a lot higher again.”

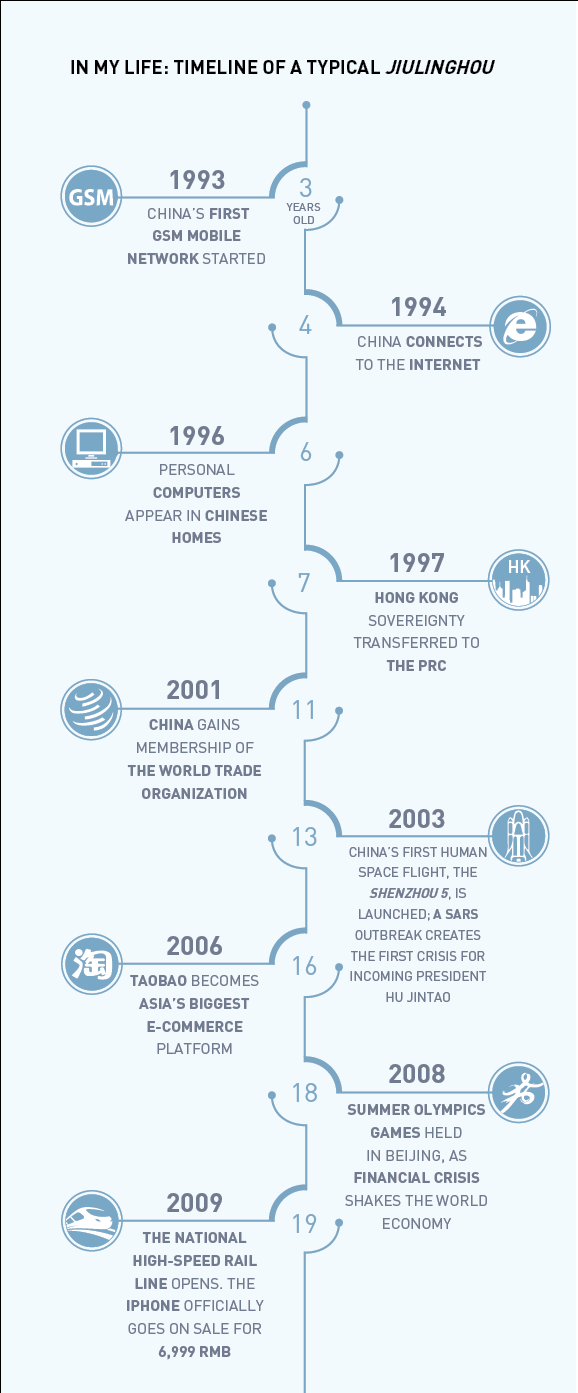

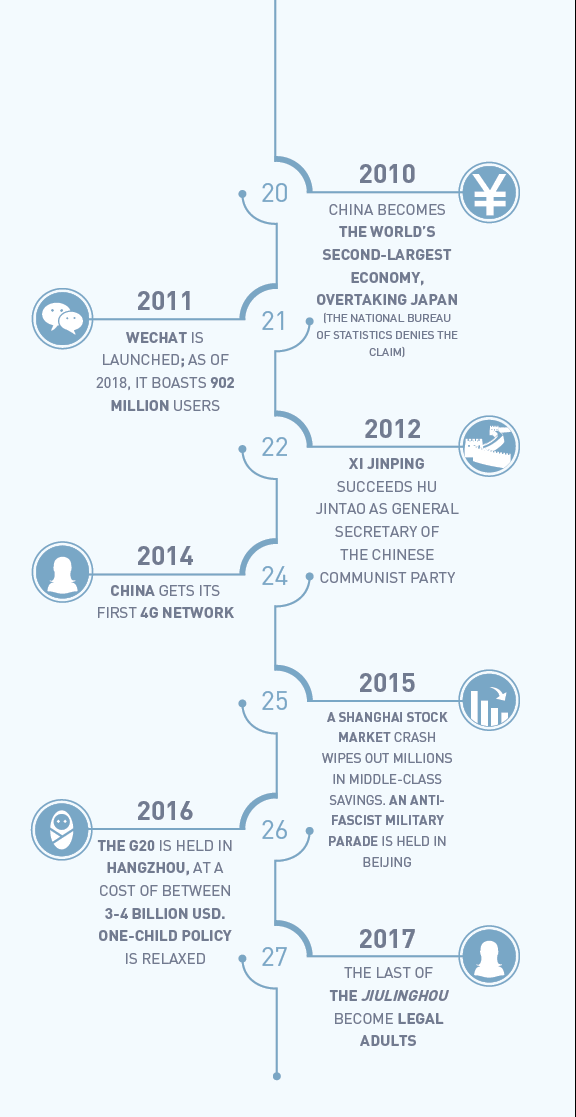

To their elders who lived through war and famine, and sacrificed individual ambitions to collective dreams, Dai’s is known as the “lucky generation.” Other than this, there is no real Chinese word for “millennials,” the term that American pop historians coined in the early 1980s for individuals born between the 80s and the turn of the millennium. Though the direct translation is qianxiyidai (千禧一代), in China, it’s more common to hear this demographic further broken down: the “post-80s” (balinghou 八零后), “post-90s” (jiulinghou 九零后), and “post-00s” (linglinghou 零零后).

Although separated by only a few years, these generational divides matter. This has everything to do with China’s extraordinary speed of development since the reform and opening up era. Children of China’s economically re-stabilizing 90s, and adolescents in the politically confident millennium, thejiulinghou have parents with just dim memories of the Cultural Revolution and who reached adulthood right after the 1978 market reforms. Compared to their “post-80s” predecessors, thejiulinghou grew up with unprecedented access to education, consumer goods, pop culture imports, and of course, technology and social media platforms to link them to the rest of the world (Great Firewall notwithstanding).

But the drastic and uneven changes to the state, market, and society have also given the jiulinghou whiplash. Unlike the balinghou who came of age before the 2008 financial crisis, and compared to the still-youthful linglinghou, those of the post-90s generation now find themselves in a bind: Surrounded by “new world” goodies, but unable to afford them; straddling the uncomfortable line between new ideals and old values, jiulinghou are coming of age, in a nation both trying to “re-emerge” as a global power and assert certain ideologies it feels are key to its stability and harmony at home.

***

On New Year’s Eve, 2017, the hashtag, shiba sui zhao (十八岁照), essentially “me at 18,” began trending on Chinese social media platforms. Sharing photos of themselves at 18, Weibo and WeChat users welcomed the 18th year of the millennium with a nostalgic look back. It was also, noted China Daily, a bittersweet acknowledgement that as of the new year, even the youngest jiulinghou will have become legal adults: The post-90s are putting aside their adolescence, and the post-00s taking it up.

A shopper checks out the array of cheap consumer electronics as Beijing’s Joy City Mall (Gopa Biswas Caesar)

For China’s post-90’s generation, one term used to describe their journey into adulthood is “awkward”—or the Chinese 不三不四, literally “neither three nor four.” A short article on China.com summed up the headaches of the post-90s’ generation as:

Too early to get married, yet too late to start dating. Play around? No time. Make some money instead? Too difficult. Spend money? None to spend.Too young to socialize with the post-80s, yet too old to hang with the 00s.

“Neither three nor four,” though, is also an apt description for the China into which these newly minted adults graduate, product of an accelerated modernization that took other countries centuries to achieve. “[Our] pressure often comes from the increasingly wider choices of ways to live, as traditional, modern, Eastern, and Western lifestyles are presented to us,” says Song Yu, a jiulinghou journalist residing in Beijing, comparing the travails of his generation to those that came before. “It’s hard to foresee the results of our individual choices, which is stressful, compared to the older generations whose lives were partly determined by society and Chinese traditions.”

These traditions often intertwine with economics to create unique challenges—such as the property bubble. “There’s a tradition in China of being ‘settled,’” says Song, who finally became owner of his own Beijing property this year. “Even if they have to empty their life savings, even if prices in first-tier cities never fall, any family that is able will choose to buy an apartment.” Renting, in his opinion, “can lead to disputes and trouble,” and his parents, who live in a small city in Shandong province, “literally spent all their savings to cover my down payment, hoping this will reduce the burden of my monthly payments.”

Settling, of course, implies marriage. With home-ownership considered a prerequisite before a couple gets hitched, and marriage before one’s 30s a “familial duty,” property becomes the wisest investment in an economically and romantically unstable era characterized by low credit, low trust, “scam marriages,” and a rising divorce rate. In the first half of 2017 alone, 1.85 million couples cut their legal bond, a 10.6 percent increase from the same period the year before.

“Of course, I’m happy to own a home,” says Song, “but it’s more so that my parents can stop worrying.”

Other post-90s, though, have chosen to push back against the traditional, heteronormative expectations of marriage, to the extent that the state has begun to fear for its future stability. From the All-China Women’s Federation’s adoption of term “leftover woman” in 2007, describing women still unwed by 27, to the relaxing of the one-child policy in 2016, politics are also conspiring with economic and cultural pressures to push millennials up the property latter.

In 2016, following amendments to the family planning policy, provinces began to remove incentives for “late” marriage—defined, under Chinese law, as men marrying later than age 25 or women later than 23—such as extra days off and bonus pay, out of concern that on average, Chinese were waiting until 25 to get married, according to a National Health and Family Planning Commission spokesperson in 2016.

The state’s own inertia, though, that has created one hurdle unique to the Chinese millennial: The country’s internal household registration or hukou system, a relic of the planned economy. As of 2016, balinghou and jiulinghou comprised 64 percent of China’s 254-million strong “floating population,” who do not hold a hukou and therefore cannot access health, education, and other social services in their city of residence—even if they were born there.

Song says the Beijing hukou offered by his employer was a “major consideration” when weighing job offers after graduation, the “first step” in his journey to home-ownership. For the rest of the country’s 44 million floating jiulinghou, though, even “reading” their way out of modest hometowns into top colleges and jobs in first-tier cities is no guarantee they can stay.

And for post-90s like Dai, for whom the chips have fallen just right—Shanghai hukou, well-off parents, prestigious job—there’s the ennui of simply being at the short end of China’s neoliberal boom. “For the post-80s,” Dai reckons, “the housing prices [were] not [as] high at the time when they wanted to get married.” Meanwhile, the post-00s seem to have more of a safety net, with parents—many of whom are balinghou—who already started climbing the property ladder.

Indeed, one counterpart to the “lucky generation” label is the “cheated generation.” As one joke goes:

When [balinghou and jiulinghou] were in primary school, university was free; when we entered university, primary school became free. Before we had to buy houses, the state gave them out. They raised the retirement age when we started working; the stock market crashed just as we started buying. And when we thought we could enjoy being adults for a while, the state wants us to get married and have a second child.

In 2015, online variety show Baozou Big Affair added its own punchline to the above: “And we’re still accused of being ‘the morally degenerate generation’ by those elders [who] square dance to disruptive music…created pollution, and make tainted foods.”

***

So how much avocado toast does it take to buy an apartment in Shanghai? Some of Dai’s peers are no longer interested in finding out. “[Since] the housing prices are too high, some just want to rent,” he relates.

The post-90s have been called out, almost pityingly, for internalizing a culture of deliberate despondency, known as sang (“depressed”). In the past two years, the subculture had become a trendy IP, spawning “negative energy” milk tea and yogurt brands, icons like the “Ge You Slouch” and Gudetama “Lazy Egg,” and even an anthem—the Rainbow Chamber Singers’ 2016 viral hit “Feels like My Body is Hollowed Out.” All have found an audience among jiulinghou who respond to seemingly impossible expectations by choosing apathy.

For other millennials, known as “Buddha-like youths” (佛系青年), conspicuous consumption, social mobility, and even ideals seem like worldly ephemera, when their only objective is living a uneventful and stress-free life. According to a 2017 survey of young Beijingers, the jiulinghou frequent urban “points of interest”—shopping malls, scenic sites, and the like—10 percent less than balinghou. A separate survey of netizens found 宅 (“housebound, reclusive”) as jiulinghou’s top adjective for themselves, while “surfing the web at home” was the favorite leisure activity, chosen by 62 percent of respondents.

According to Dai, the lack of money is why some of his college friends “don’t socialize anymore.” “If you go out for a drink, that’s at least 50 yuan; two drinks, 100,” he figures. “If your salary is 6,000 yuan [about average in Shanghai], if half goes to housing, you only have 3,000 to eat, buy clothes…hang out with friends and go to karaoke or an amusement park. You just stay at home, play computer games, watch online videos, or live streaming.”

Chinese youths may be foregoing public spaces, but aren’t necessarily abandoning socializing. According to Wu Changchang, a communications professor at East China Normal University, penny-pinching millennial culture has given rise to what he calls an “economy of boredom.” Live streaming, a leisure option born from a lack of time and money to socialize, has become a sophisticated online forum in itself. “About 60 to 70 percent of those who watch live streaming are youths with a monthly income of less than 3,000 RMB,” Wu says. “For most, it’s simply to kill time, [but] the other major reason is to seek acceptance.”

“A unique feature of live streaming is that the viewer is enabled to engage directly with the performer,” explains Wu. Viewers can buy virtual gifts and vie for a thank you from the performer during the broadcast. “Everyone wants to be accepted in some way—a person from the middle class might turn to buying luxury purses. If you have no money, [you can] live stream.” Millennials, young migrant laborers particularly, use live streaming to redefine what it means to be social when commercial entertainment is out of reach and mainstream media is unsympathetic to their plight.

These passive rebellions against normative achievements and values haven’t gone without official pushback. As early as 2016, party newspaper Guangming Daily ruled that continuous exposure to sang language “could influence people’s attitudes…and pose a great threat to personal growth and social harmony.” In January 2018, sang content, along with hip hop and tattoos, was banned from broadcast by censors; the following month, another regulation removed dozens of popular live streamers and streaming genres, such as hanmai (“microphone shouting”), from streaming platforms.

To the post-90s, though, breaking convention can lead to boundless creativity. Fed up with the pressure to land a nine-to-five jobs (not counting overtime), 74.3 percent of university students report having peers who already created their own start-ups and small and medium enterprises, according to a 2015 study by the China Association of Science and Technology. In a Renren.com survey the same year, 71 percent of university entrepreneurs claimed they started their own businesses to express individuality.

Engineering students test out their robotics prototype at the mall (Gopa Biswas Caesar)

The jiulinghou were behind several apps that have attracted high-profile investments in recent years, from the founders of BaohuDoudou and Zhan.com, devoted (respectively) to sex education and study abroad, to Chen Anni, the artist who turned her comics on Weibo into KuaikanManhua, China’s top comic-reading platform.

Still others may find alternative pursuits in valuing the importance of the “now,” even if that means foregoing the dream—or duty—of stability, saving, and sacrifice, and instead focusing on personal development, leisure, or traveling abroad (see “The Parent,” page 38)

Ultimately, being jiulinghou means being different; every bit of criticism, praise, and pity for this embattled generation is founded upon some reality of the complex world they are trying to navigate. While it’s impossible to generalize across China’s complex and diverse landscape, this much is true: In an era “neither three nor four,” there’s opportunity to be both. One can chase property or prospects, as well as order a slice of avocado toast—or even some entirely new item of their own concoction.

The Noughty Nineties is a story from our issue, “The Noughty Nineties.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.