Treating the psychic tremors of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake

In a quiet corner of the Beichuan Rehabilitation Center for the Disabled, 49-year-old Xiao Zhao sits in a wheelchair with her legs propped up as she embroiders a cartoon panda, her needle see-sawing gracefully through a white handkerchief.

“I’ve been having nightmares again about houses collapsing,” she says shaking her head. “Sometimes I have dreams that I can still walk, but when I wake up, I feel even worse. Once I had a dream that not only my legs, but my arms were broken too—I woke up crying.”

On May 12, 2008, a Richter Scale 8.0 earthquake turned entire mountain towns in Sichuan province into rubble, claiming the lives of 69,227 people, injuring 394,643, and leaving 17,923 missing in the ruins. Years afterward, devastated communities struggle not only to rebuild their houses and families, but to recover a sense of worth and hope.

At 2:28 p.m. on May 12, 2008, Xiao was at home caring for her grandmother when the ceiling came down, and her memory cut to black. A neighbor picked her out of the rubble and carried her on his back to an open field, where she waited for medical assistance the whole night as rain began to fall. It would be another week in the overloaded medical system before she received surgery.

In the largest earthquake relief effort in modern Chinese history, Chengdu’s four largest hospitals took in 2,000 casualties, with over 80 percent seriously hurt with broken bones, spinal injuries, or head wounds. More than 5 percent needed an amputation. With 6.5 million homes destroyed, 15 million residents were evacuated from their homes, and 5 million lived in government-built temporary shelters.

In 2009, the province reported that the quake left 7,000 people with physical and mental disabilities. In 2011, an academic study found that 8.8 percent of those from heavily impacted regions showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“There was a lot of money flooding in afterward to help disaster-stricken people. But the most difficult challenges to overcome were inside us,” says Xiong Tingyun, who was principal of Leigu Elementary School during the quake when its two buildings collapsed, killing two of his students as well as his own son.

Five million people were rendered homeless by the earthquake (VCG)

The Sichuan earthquake was the first time China’s burgeoning field of psychology had to respond to a large-scale natural disaster.

Three decades prior, in 1976, a Richter scale 7.8 earthquake hit Tangshan, Hebei province, claiming 242,000 lives. There had been no psychological aid during this second deadliest earthquake of the 20th century—psychology departments had been shut down at universities during the Cultural Revolution.

Tangshan psychiatrist Dong Huijian told Beijing News in 2016, “The lack of psychological aid after the earthquake due to the social and medical conditions of the time resulted in too many Tangshan patients with PTSD.”

Dong herself suffered from panic attacks due to loud noises, and had nightmares about her mother who died in the quake. An academic study by Dong, surveying 5,000 people 30 years after the quake, found that 70 percent still suffered negative psychological effects, including PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

Psychology departments were reinstated at China’s universities in 1978, and by the turn of the century, there were 100,000 psychology students across the country. Psychological health was added into the national public health program in 2004. Dong, orphaned at 15 in the Tangshan Earthquake, became the first person in China to receive a PhD in disaster psychology in 2006.

The first instance of organized psychological first aid following a disaster took place after a fire in Xinjiang killed over 300 people in 1994. Local hospitals, overwhelmed with patients with acute stress-related conditions, appealed to the Ministry of Health for support, who in turn dispatched a team of clinical psychologists from the Peking University Institute of Mental Health.

The team continued to respond to the 2002 Dalian air crash, 2003 SARS epidemic, and 2004 Yunnan typhoon. However, psychological first aid was not well understood by the public, and volunteers were sometimes even regarded with hostility when they showed up at disaster sites, says Ma Hong, a psychiatrist at the Peking University Sixth Hospital.

It wasn’t until the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that psychological aid burst into public conversation, as the emotional distress of the disaster was widely reported in the media. In the first month after the quake, over 1,000 mental health professionals arrived in Sichuan, including psychologists, psychiatrists, and counselors from the army, hospitals, universities, and private clinics.

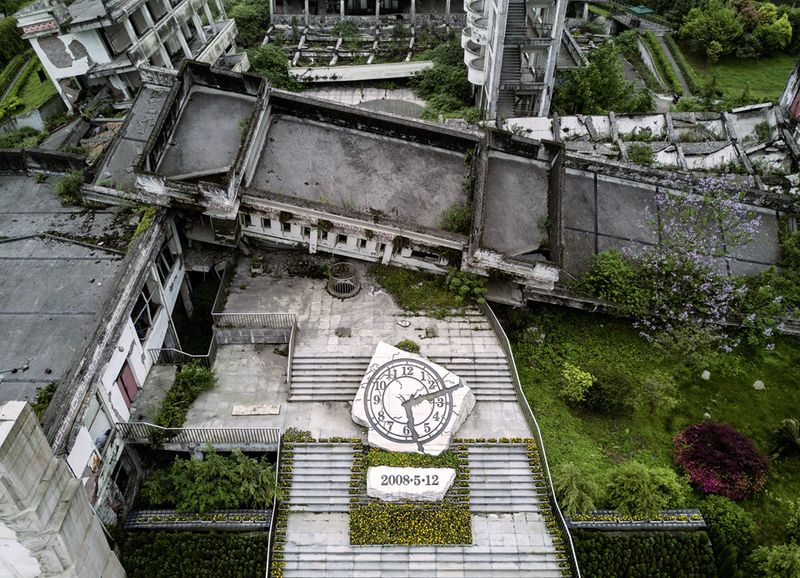

Xuankou Middle Scool’s ruins are now a public memorial (VCG)

“Many of the survivors’ faces were wooden; they hadn’t fully realized what had happened yet,” recalled Shi Xiangmei, a 48-year-old psychiatrist at Chengdu’s West China Hospital who volunteered for the disaster relief. One 3-year-old girl from Yingxiu town was discovered by the team after having sat by her mother’s corpse for two days and nights, and had ceased eating and drinking due to emotional distress.

Volunteers patiently coaxed the girl with games, eventually building a relationship of safety and trust that helped her recover over months. But the challenges were many: Older residents of the Qiang, Yi, and Tibetan ethnicities didn’t speak Mandarin, and many were not accustomed to sharing their families’ intimate woes with strangers from the city.

“We had to shift our thinking,” noted psychiatrist Deng Hong, lead organizer of West China Hospital’s aid effort. “In the hospital, there are long lines of patients waiting outside of your door. But in the neighborhoods, nobody is looking for you. We needed a new model for how to go in and provide care to a community.”

Psychiatric teams set up counseling offices in schools, and adapted a Hong Kong curriculum for fostering resilience for elementary school students. The counseling office was open for drop-in meetings one day a week, and some children were invited for individual psychotherapy. For three years, they organized a summer camp for orphaned children.

Volunteer counselor Mo Xiaohong held multiple small group sessions, including a Qiang embroidery circle. Singing Qiang songs at times became a shared vessel for grieving. One group was dedicated to bereaved mothers, attended by 46 women who wanted to bear children again.

“We need to combine Western psychiatry with local culture, reaching out to the community in local language and with respect to local customs. Additionally, cultural resources can be a point of connection and emotional healing,” said Deng.

Yet 12 years on, even as many of Principal Xiong’s students have entered college, and parents have welcomed new children into the family, many Sichuan residents still struggle to make sense of the pain.

One Friday night, the father of one of Xiong’s students got drunk, wrapped his wrists in electrical wire, lay down next to his wife, and electrocuted them both.

“Despite our work, we do hear about cases of suicide,” said Mo. “It’s difficult to say who is to blame.”

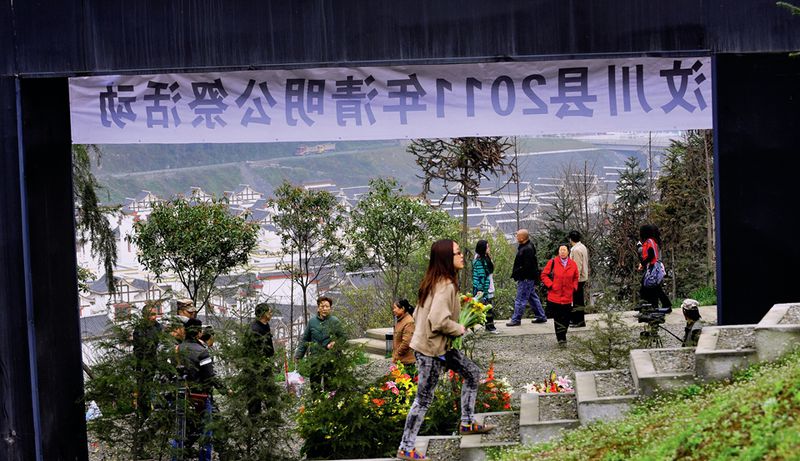

Families of earthquake victims come to sweep tombs on the Qingming Festival (VCG)

Nevertheless, the earthquake has left the landscape of disaster relief in China permanently changed, as the fledgling discipline’s haphazard beginnings develop into a better integrated and prepared psychological first aid system.

For a generation of Chinese psychologists, psychiatrists, and counselors, Sichuan was a training ground for new modes of psychological aid and new techniques for reaching vulnerable communities. “The world’s experts all came [to Sichuan]. Professors and students had opportunities for training and practice,” says Gao Jinying, a Hong Kong family psychologist who volunteered after the quake.

Many of the same teams formed in Sichuan continued to mobilize for the 2010 Qinghai earthquake, 2010 Gansu mudslide, 2015 Tianjin port explosions, and 2018 knife attack in Shaanxi.

Professionalization and standardization remain ongoing efforts. In May 2018, on the 10th anniversary of the Sichuan earthquake, an international symposium on psychological aid hosted by the Chinese Psychological Society and the Chinese Academy of Sciences outlined the nation’s post-disaster intervention work standards, including guidelines on informed consent and the protection of privacy.

“We had no concept of mental health before the earthquake; only after did we learn about how important it was,” reflected Principal Xiong. Mental health is still a fresh concept, especially in rural areas, and a lack of broader mental health education prevents many from accessing psychological services.

Since the earthquake, China has implemented its first mental health law in 2012, and the first national five-year mental health work plan in 2015, to protect the rights of mental health patients and promote the development of the sector. Frontline volunteers have returned to Chengdu and founded China’s first internationally certified community rehabilitation center to continue serving patients outside the hospital ward.

Xiao puts the finishing touches on the piece of embroidery that has taken her two hours, for which she will receive 8 RMB. She subsists primarily on dibao, or subsistence allowance from the government, and passes her days alone in the rehabilitation center with a daily video call to her newborn grandson back in the village.

“I started embroidering to take my mind off the pain,” Xiao says. “Pillowcases, hats, dresses, flowers, pandas, little birds, butterflies; anything you can draw, I can embroider.”

“Or else my nerves hurt so much I could cry,” she mutters. “There’s nothing to be done: It will be aching every day for the rest of my life.”

Cover image from VCG

“Aftershocks” is a story from our issue, “Disaster Warning”. To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.