From carriers of mail to emperors’ pets, the zodiac animal had a special place in ancient China

During the Spring Festival of the Year of the Dog, 旺 (wàng, “prosperous”) is a ubiquitous season’s greeting. Sharing the same pronunciation as 汪 (wāng), the onomatopoeia for a dog barking, it was the perfect blessing for any time of year.

One of humankind’s oldest companions, dogs were essential to the livelihood of not only households, but entire kingdoms in ancient China. Guan Zhong, a chancellor and reformer of the state Qi during the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE) wrote that families could enrich the state specifically by raising the “six domestic animals,” or 六畜, which are horse, ox, sheep, chicken, pig, and dog. Today, farmers still frequently paste the characters “six domestic animals thriving” or 六畜兴旺, over their stables as a Spring Festival blessing.

The dog is also the 11th of the 12 Chinese zodiac animals. According to the legend, in the race organized by the Jade Emperor to determine the order of zodiac animals, the dog ran side by side with its friend, the rooster. Just as they reached the finish line, though, the rooster flapped its wings and finished one place ahead. From that moment on, the dog and rooster became enemies, hence the many idioms with negative connotations that involve dogs and roosters.

In another myth recorded in the Book of the Later Han, a fifth century Chinese historical record, an ancient emperor named Di Ku offered his daughter’s hand in marriage to whoever could kill his enemy general. Panhu (盘瓠), a “dog god” with furs in five colors, showed up and bit off the general’s head off. The emperor kept his promise, and Panhu and the princess were said to be the ancestors of several southern minorities. In another retelling, Panhu was able to transform into a human if he stayed under a giant golden bell for seven days.

Mythology aside, DNA evidence leads some scientists to believe that dogs were first domesticated in the south of the Yangtze River, 16,300 years ago. But the earliest dogs remains were discovered in northern China—Hebei province, dating from 10,000 years ago, according to archeologist Yuan Jing at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The discovery of dog bone remains near settlements suggested that dogs guarded villages as well as helped hunters.

A dark fact about dogs in ancient times is that they also served as a food source. In many remains dated to the Shang dynasty (1600 BCE – 1046 BCE), fragments of dog bone bones were discovered with bones of ox and other domesticated animals. However, during Sui (581 – 618) and Tang (618 – 907) dynasties, the culture of the Central Plains became influence by nomads from the north, who valued dogs in herding and hunting; the period also the rise of Buddhism and vegetarian doctrines. Dog meat began to disappear from the tables of the emperor and aristocrats, and eating dog was regarded as vulgar.

On the other hand, as companion and loyal friends, dogs have won the hearts of emperors and common people alike. Emperor Wu of Han, from the second century BCE, housed his dogs in a palace in the imperial garden, known as the “Dog Terrance Palace.” Emperor Ling of Han, who ruled 300 years later, putting his dogs in tall caps like human courtiers.

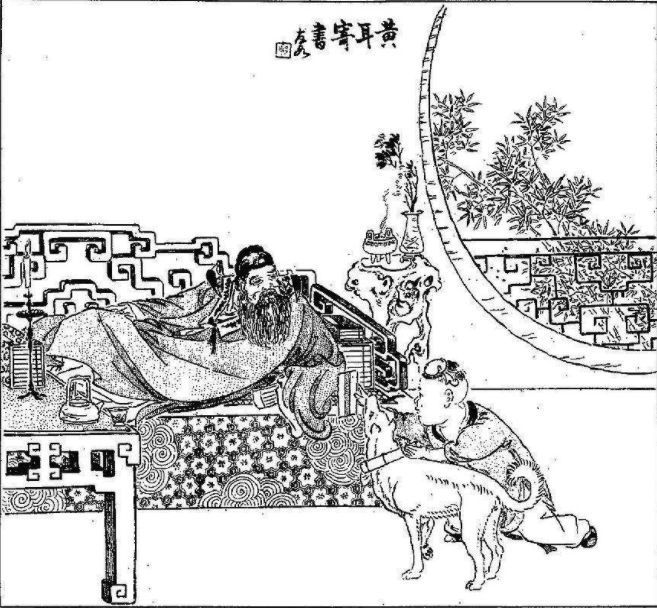

An illustration depicting the tale of Yellow Ear

Dogs were also loyal servants, as told in the fifty century book of tales, The Accounts of Marvels (《述异记》): Lu Ji, a writer and official in the third century, was working in the capital away from his family. For a long time, he didn’t receive any news from home and became worried. He jokingly asked his dog, “Yellow Ear,” if it could carry a message from him to his family. Yellow Ear wagged his tail and appeared very happy to oblige. Lu then wrote a letter, put it in a bamboo container, and tied it to the neck of the dog. Yellow Ear traveled day and night, delivered the message, and even brought back a reply. It was a long trip that would cost people 50 days there and back, but Yellow Ear only took 20 days. Because of this miraculous tale, “Yellow Ear delivering a message,” or 黄耳传书, became a synonym for sending a letter home.

“Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers,” by Zhou Fang

In the Tang dynasty, dogs were one of the favorite companions of noble women as depicted in the painting Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers, by Tang artist Zhou Fang: two small “lion dogs” frisking around a group of court ladies, one of whom is playing with the dog with a horsetail whisk.

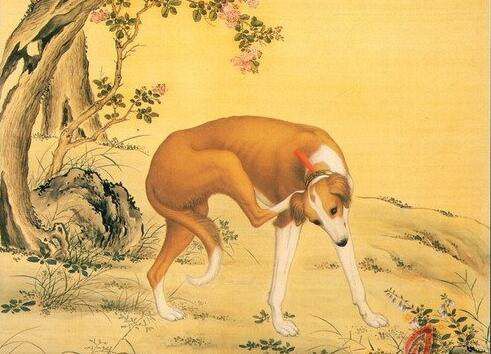

Dogs became even more popular as pets in the Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing (1616 – 1911) dynasties, with several famous Chinese breeds developed in this period, such as the Shar Pei and pug. Dogs were especially loved in the Qing court. Hunting dogs started as favorites of the Manchu emperors who came from a nomadic culture. The Yongzheng Emperor, known for his diligence, actually made time in his busy schedule to design clothes, a bed, and hats for his beloved dogs. As the Manchu rulers settled into a peaceful and opulent lifestyle, the court’s favorite breed became the smaller Pekingese, also known as “lion dog” or 京巴儿 (jīngbā’er). The Empress Dowager Cixi kept a dozen of small dogs, but her favorites, “Sea Dragon” and “Black Jade,” were both Pekingese.

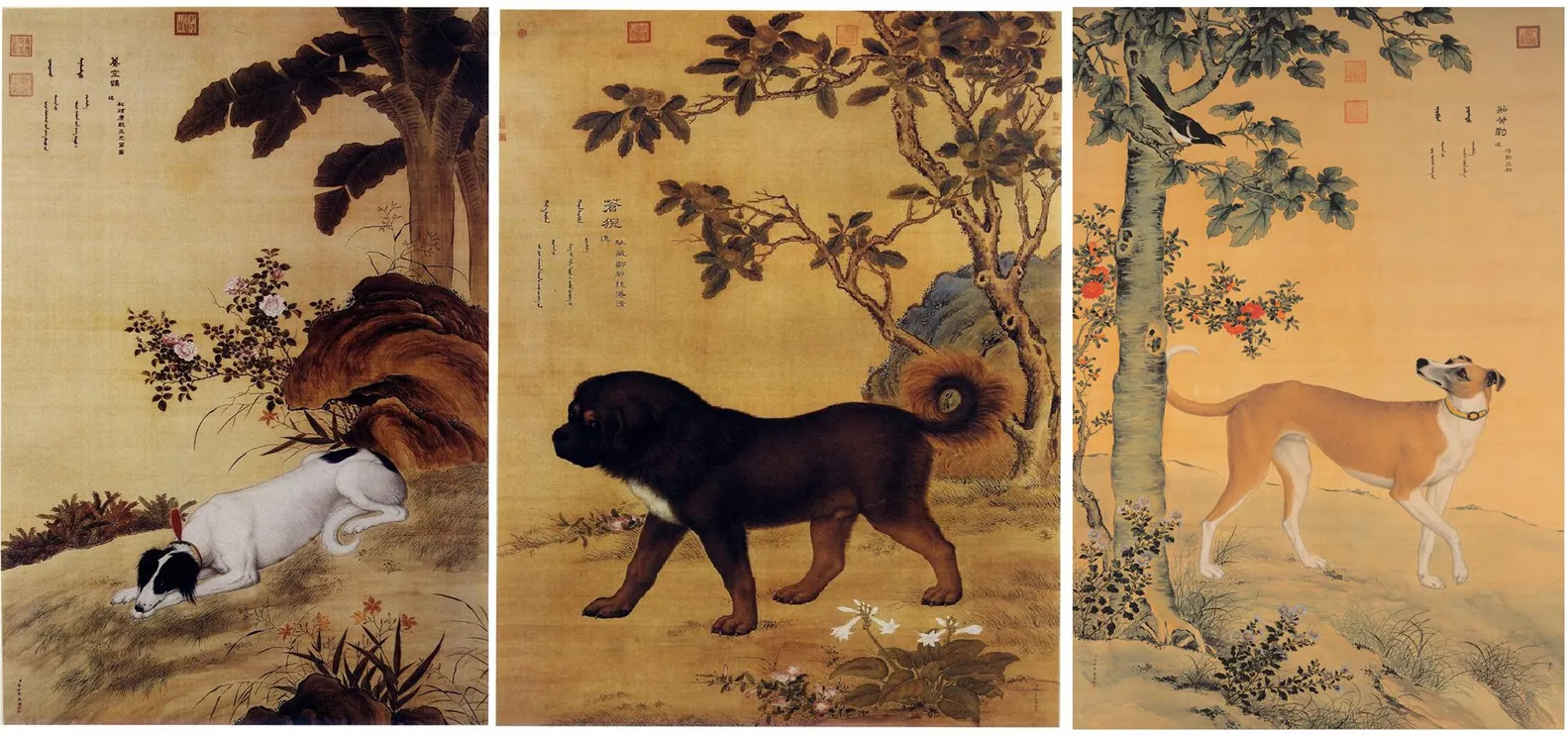

A painting of a court dog by Lang Shining (郎世宁), or Giuseppe Castiglione, Qing court painter in the late 17th century

From myth and legends to history, dogs had a special place in the lives of the ancient Chinese, as well as all human civilizations. Over the millennia, the canine-human dynamic has evolved with time. In the Year of the Dog or any other year, we hope all your endeavors will be 旺旺旺!