How the Yangtze River region became China’s premier cultural hub

“People here all have delicate and white skins, with the females, in particular, boasted with bright eyes and fine features,” the Venetian adventurer Marco Polo wrote of China’s Jiangnan region in The Travels of Marco Polo in 1298.

Refinement in features and gentleness in characters are archetypes that the Chinese have long assigned to people living in this southern locale, who are described as “shuǐ líng (水灵, clever and beautiful)” and “xiù qì (秀气, fine featured).”

Enjoying an extensive networks of river and waterways, Jiangnan is one of the most fertile plains in China, as well as one of its earliest commercial hubs. Consequently, its prosperous towns gave the region its nickname “the land of fish and rice (鱼米之乡).”

Not everyone agrees on the geographic boundaries of Jiangnan, though it’s name literally means “South of the [Yangtze] River.” This generally comprises present-day central and southern Jiangsu province, Shanghai, Zhejiang province, southern Anhui province and some regions in Jiangxi province. Cities that fall under this definition include Suzhou and Nanjing in Jiangsu, Hangzhou and Shaoxing in Zhejiang, Huangshan and Anqing in Anhui, and Wuyuan in Jiangxi.

The ancient cultural hubs of Suzhou and Hangzhou, though, are considered the most representative Jiangnan burgs to both Chinese and foreign visitors. As a proverb goes, “Up in the skies, there is heaven; down on earth, there are Suzhou and Hangzhou (上有天堂,下有苏杭).”

Many Jiangnan towns, such as Wuzhen in Zhejiang province, are known for their canals

Jiangnan owes its beauty and prestige to a quirk in Chinese history. The cradle of the Chinese civilization was traditionally located farther north, along the Yellow River rather than the Yangtze, where many prehistoric civilizations appeared. Many dynasties also settled their capitals in northern China, leading central and north China to become regions of military importance.

However, starting from the Western Jin Dynasty (266 – 316), the north became embroiled in countless civil wars, and a large-scale north-to-south migration of Han civilization began, called the “Yongjia Southern Migration” (永嘉南渡). Many aristocratic families were part of this movement, bringing their advanced agricultural technologies, as well as Confucian learning, to the then sparsely populated middle and southern reaches of the Yangtze River.

Jiangnan’s prestige was further cemented in the last millennium, as more aristocrats escaped to the south due to invasions by steppe empires in the north, culminating with the Southern Song dynasty relocating its capital from the Yellow River-adjacent Bianliang (now Kaifeng, Henan province) to Lin’an (Hangzhou). Jiangnan entered its golden age due the influx of talented administrators and literati, as well as its economic advantages. For this reason, By the middle of the Qing dynasty (1636 – 1912), the region paid one-third of all the taxes in the empire.

Today, Jiangnan is known for its food, handicrafts and architecture, all of which speak to a spirit of elegance. Take Huaiyang (淮扬) Cuisine as an example: One of the best-known food cultures from Jiangnan (along with Anhui, and Zhejiang Cuisine), it’s renowned for its chefs’ proficient cutting technique (刀工), creating exquisite “food carvings” (菜雕) achieve a perfect combination of color, aroma, and taste.

Aquatic products are also the quintessence of Huaiyang food, which originates from the river towns of Huai’an and Yangzhou. These are usually cooked to a delicate taste by simmering, steaming, braising, stewing, and frying. Probably the most representative Huaiyang dish is the steamed pork meatball with crab roe (清蒸蟹粉狮子头), which combines cooking wine, ginger, green onion for an extremely tender and fresh taste, and is usually served within a light soup.

Steamed pork meatball, with crab roe or a clear soup, is the quintessential Huaiyang dish

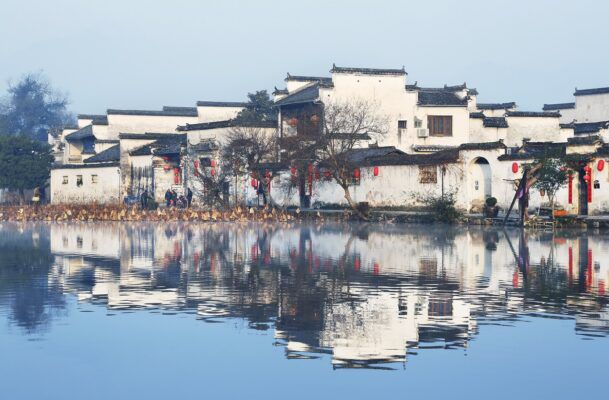

Jiangnan is also quite famous for handicrafts like Suzhou embroidery and kernel carving, known for their abundant patterns, smooth texture, and exquisite handiwork. But the most familiar element of Jiangnan culture to tourists, and one that often gets mistakenly assigned to the region as a whole, is Huizhou architecture: namely, “whitewashed walls and black tiles” (白墙青瓦), carved rafters, airy courtyards, and bridges arching over ponds or the region’s ubiquitous rivers and canals.

Commonly seen in villages like Hongcun in Huangshan and Likeng in Wuyuan, these garden-like architectural complexes (as well as Jiangnan’s renowned gardens themselves, represented by the “literati gardens” in Suzhou) have also been adapted into imperial complexes like Summer Palace in Beijing and the Summer Resort in Chengde, Hebei province.

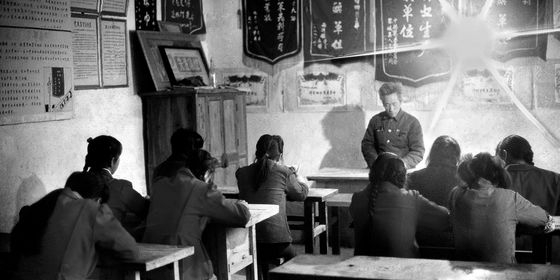

Jiangnan was also renowned for its educated residents and literary culture. As an ancient saying goes, “In the Ming and Qing dynasties, over half of the top officials come from the Jiangnan region”(天下英才,半数尽出江南).

Though commerce was bringing Jiangnan great prosperity by that time, wealthy local families still preferred to educate their children classically. The Jiangnan Imperial Examination Hall (江南贡院) in Nanjing was the highest educational institute and the largest and most influential examination site in ancient China along with Beijing’s Imperial Academy. Well-known authors from the region include Wu Cheng’en, a Huai’an native who wrote Journey to the West, and Nanjing-born Cao Xueqin, who wrote Dream of the Red Chamber.

Hongcun village is a popular spot for tourists to view Huizhou architecture

Jiangnan remains China’s most economically developed region, with one “first-tier” city, Shanghai, and cities like Nanjing, Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Ningbo. Thanks to its geographical location, Jiangnan’s economy has exerted a huge influence both at home and abroad: Zhejiang’s entrepreneurs are known all over the world, and the province is now a pioneer in the country’s digital economy.

Attracting tens of millions of Chinese and international tourists each year, Jiangnan continues to enchant, much as it did in when Tang dynasty poet Bai Juyi wrote in “Dreaming of the Southern Shore [Jiangnan]”: “Fair Southern shore/ With scenes I adore/ At sunrise riverside flowers redder than fire/ In spring green waves grow as blue as sapphire/ Which I can’t but admire. (江南好,风景旧曾谙。日出江花红胜火,春来江水绿如蓝。能不忆江南?).

Photos from VCG