The Manchu pigtail was the most controversial haircut in Chinese history

In 1911, when the Qing dynasty crumbled, Han Chinese everywhere enjoyed a haircut. The long-braided pigtail or “queue” (辫子, biànzi) they had been forced to adopt since 1644 was discarded as a symbol of Manchu oppression, and wave of new hairstyles began to sweep the country along with the promise of the new Republic of China.

The hairstyle had been first widely introduced to the Han population in 1644, when the Manchus breached the Great Wall with the help of traitorous general Wu Sangui, and conquered what was left of the Ming empire. The new Qing regent, Dorgon, enacted many new reforms to consolidate the empire, including throwing out the more troublesome court eunuchs, bringing back the imperial examination system, limiting intermarriage between Manchu and Han, banning foot-binding—and making Manchu dress and queues mandatory for Han men.

The bianzi is described as a traditional Manchu hairstyle by the 12th century’s Collected Records of the Northern Alliance During Reigns of Three Emperors (《三朝北盟会编》), which noted that Manchu men “shaved their foreheads and braided the hair in the back of their head into a braid hanging straight down.” This custom was “wildly different” from that of Han men, who were “forbidden to shave their heads on reaching adulthood.”

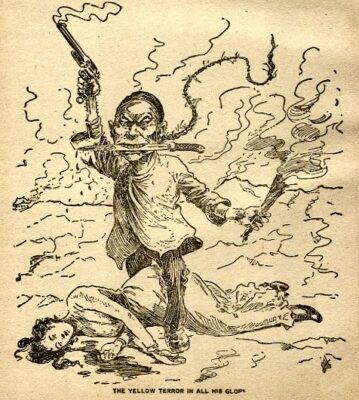

Overseas, the queue appeared in many xenophobic cartoons about Chinese immigrants in the 19th century (Wikimedia Commons)

Dorgon issued the first “Hair Shaving Edict” (剃发令) shortly after the Qing conquest, but protests and a series of peasant revolts forced him to scale back the order; it was considered a particularly humiliating for Han nobles, who prided themselves on their highly individual, stylized haircuts, usually worn long and bundled into elaborate buns or ponytails. In July of 1645, however, Dorgon reinstated the edict on pain on death, sending soldiers to cities to act as barbers and chant the slogan “Your hair or your head! (留头不留发,留发不留头。)”

Bianzi enforcement was lax in many regions, with many officials reluctant to prosecute the matter too harshly, or admit to signs of rebellion in their own region (Buddhist monks and Daoist priests were also exempt). But over time it did start to stick, and created resentment. The order also effectively radicalized many Ming loyalists to take up arms again, spurring a century of rebellion sometimes referred to wryly by historians as the “anti hair-shaving struggle.”

Folklore and revisionist nationalism have romanticized some of the resistance to the queue, as well as men like historian 17th-century historian Zhang Dai, who became a hermit rather than submit to the scissors. But in reality, the majority eventually came to grudgingly accept the tonsure, and indeed, Qing rule. The hairstyle even evolved a few times throughout Qing rule: early iterations required men to shave off all their hair except a patch the size of a coin in the back, and a thin braided lock hanging down, while men at the end of the empire only had to shave their forehead.

Even so, there were many token acts of resistance, such as unbraiding the end of the pigtail, letting the hair hang loose, or wearing a turban to conceal the style. Followers of the 19th century’s Taiping Rebellion were known as “long hairs” or “hairy rebels.” This on-off history of hairy resistance toward the queue was to prove long and complex, with bizarre interludes such as the “sorcery scare” of 1768, when magicians were allegedly cutting and saving men’s queues for supernatural uses.

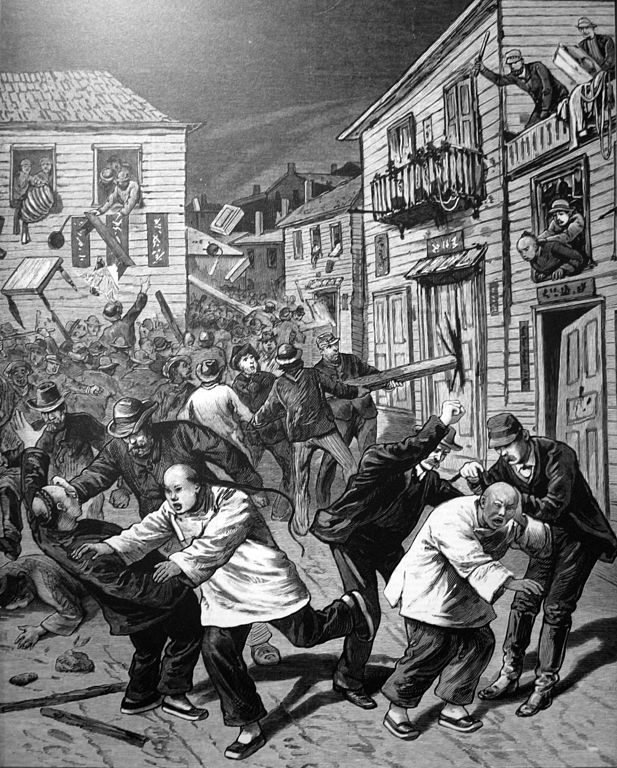

In the 19th century, the hairstyle emphasizd the otherness of Chinese immigrants abroad—rioters cut off the hair of Chinese miners in Australia’s Lambing Flat gold fields in 1861, and did the same to Chinese laborers in Colorado in the 1880s, out of the spiteful belief that a Chinese without a pigtail would be unable to return home.

Rioters tried to cut the queues of Chinese immigrants in Denver in 1880 (Wikimedia Commons)

By the dying days of the Qing in the early 20th century, the queue had firmly re-established itself as a symbol of oppression. “The Chinese people in those days revolted not because the country was on the verge of ruin, but because they had to wear queues,” claimed the writer Lu Xun, who named his dissipated character Ah Q (an allegory of a stagnant Chinese culture) after the hairstyle. Internationally, it was also a mark of humiliation: When a Chinese high-jumper reportedly hit the bar with his queue during an athletics competition in 1910, the North China Herald reported a foreign observer saying it was one of many “useless appendages” that the Chinese needed to get rid of.

The Qing empire had proved itself one of those appendages, toppled by corruption and mismanagement. Toward the wane of the dynasty, rebels in Guangdong, Tianjin, Shanghai, and the Northeast formed “hua costume and hair-cutting associations,” cutting their bianzi and adopting traditional Han clothing in an act of pragmatic revolt; and even the Qing army announced it would make all troops adopt short hair by 1912, in a desperate bid to modernize.

Before this could be enacted, though, the Xinhai Revolution broke out, led by military officers who’d enthusiastically snipped off their own braids. In cities like Nanchang, local rulers offered free haircuts to ordinary people, accompanied by celebratory fireworks. Things came full circle with Republic of China’s 1912 “Hair-Cutting Edict” (剪辫令), which saw revolutionaries forcibly cutting the bianzi of passersby in the street, amid strong protest by traditionalists. In 1922, the last Qing emperor, Puyi, cut his own queue off at the encouragement of his British tutor, putting an end to this hairy history.

Cover Image from Wikimedia