Pu Songling’s ghost stories were an escape from the poverty and disappointment of real life—excerpt from our book “Rivers Deep, Mountain High”

It is said that “every Chinese intellectual has a ‘Liaozhai’ in their hearts.” Liaozhai refers to an ancient studio located in Zibo, Shandong province, where the celebrated writer Pu Songling (蒲松龄) created his renowned collection of short stories Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (《聊斋志异》). Comprising nearly 500 “marvelous tales,” the book is full of ghosts, fox spirits, immortals, and demons—as well as young scholars and legendary beauties.

Strange Tales possesses an unshakable position in the annals of Chinese literature. Famed poet and historian Guo Moruo (郭沫若) said of the book: “The writing of ghosts and demons is superior to all others; the satire on corruption and tyranny is penetrating to the marrow.”

Pu apparently started writing those mythical stories at a young age; one of his friends wrote a poem in 1664 persuading him to stop such pointless writing when Pu was just 24. Pu kept writings and finished the majority of the content at around 40. The book itself, however, wouldn’t be published until 1740, 25 years after the author’s death. The reason was very simple: Pu was poor and had no money to publish his masterpiece.

Pu’s life was one disappointment and setback after another. He failed the imperial exams many times; he never managed to become an official and struggled constantly with poverty. Pu believed he was destined for a difficult life, claiming in the preface to Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio that a dream his father had before he was born proved that he was a reincarnated ascetic monk.

Pu was born to an impoverished merchant family in Zichuan in 1640. As with most educated men in ancient China, Pu’s life aim was to pass the imperial exam and become a government official. At the age of 18, he passed the first round of exams and that was the end of his success at exams. In the following dozens of years, Pu kept trying to take the next round but failed. It was not until he was 71 that he was awarded the title of gongsheng (贡生), a reward for his achievement in literature.

In Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, complaints about the exam system—which were often awash with bribery and cheating—are a main theme. Stories like “Ye Sheng”(《叶生》), “Si Wen Lang” (《司文郎》), and “Wang Zi’an” (《王子安》) all reveal how scholars were ruined by the imperial exams.

Financially, Pu also suffered. Pu had two elder brothers, and when they divided the property, Pu received only a small portion: several ramshackle old houses and a few poor fields. In order to support his own family, Pu worked as a private tutor for almost 45 years for a pittance. Scholars later tallied that Pu made about eight taels of silver a year. In his age, the average expenses for a four-member family were around 20 taels, and there were five in Pu’s family.

For his whole life, Pu was never rid of the shadow of poverty. So, in his works, Pu spoke out for the poor—railing against the privilege and power granted to others by the government. Such a theme can be found in works like “The Cricket”(《促织》), “Xi Fangping” (《席方平》), and “Shang Sanguan” (《商三观》).

When real life became too heavy to bear, Pu could always flee to his fantasies. Legends say that Pu often made tea with water from a spring named Liuquan (柳泉, “Willow Spring”) for local people, and collected the folk stories they told as material for his writing. That’s why his alternative name was “Liuquan Jushi” (柳泉居士, Willow Spring Dweller).

Great literature allows different people to see different things. In Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, some see beauty and love; some see the phantom of evil and despair; some see romance; some see a cruel reality, and the burden of a dejected writer.

For those who are interested in Pu Songling and his magic “studio,” the Former Residence of Pu Songling (蒲松龄故居) in today’s Zichuan, Zibo, is an ideal destination. After Pu died in 1715, his descendants lived in his residence until the houses were destroyed during the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. After the People’s Republic of China was founded, the residence was repaired, and a museum of Pu Songling was established.

Today, travelers can visit Pu Songling’s tomb in Zibo. Also, surrounding Pu’s residence is Liaozhai Park (聊斋城), a scenic area where visitors can admire the architecture, garden, and other landscapes themed around Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio.

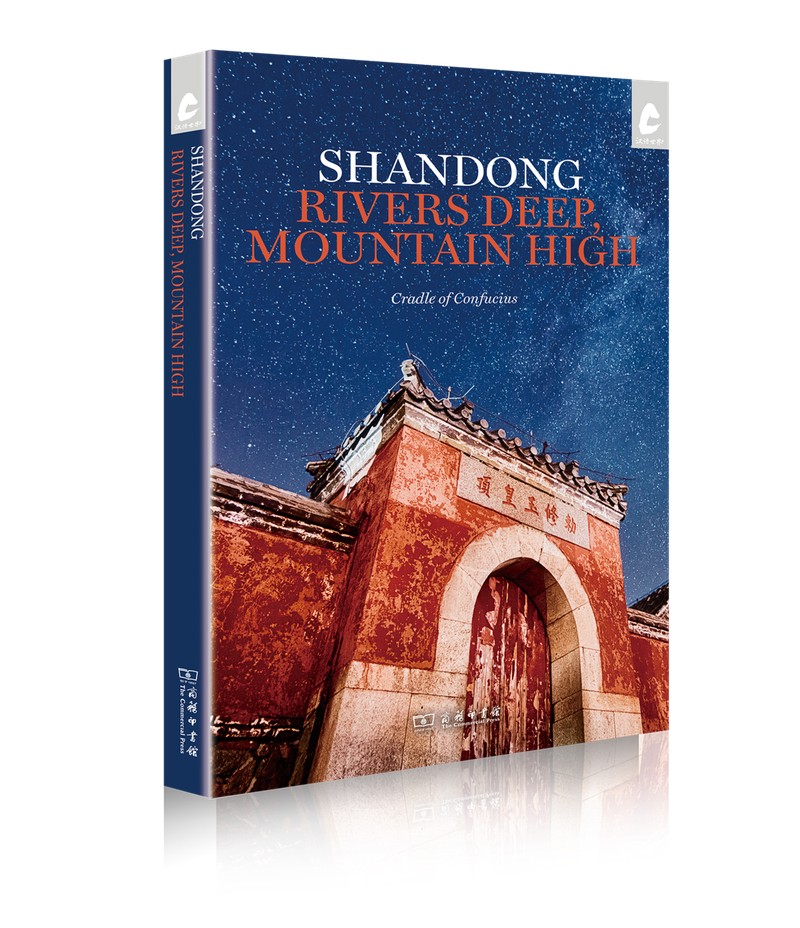

Cover image is Statue of Pu Songling in Liaozhai Park, Zibo

Read “The Half-Fox Girl,” a marvelous story from Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio retold in English by Jack Hsing

Excerpt taken from Rivers Deep, Mountain High, TWOC’s newest guide to Shandong. Get your copy today from our online store.