A close look at Pu Songling’s immortal short stories

For centuries the imperial examination was the de facto method for members of any strata of Chinese society to join the ranks of the scholar-bureaucrat class. Success in the exams, in many ways, was central to success in society. Many, many men failed.

However, Chinese bureaucracy’s loss was Chinese literature’s gain. It turns out that years of literary education, coupled with a harsh spoonful of bitter failure and ample free time, are a recipe for authorial success. Chinese literature is so littered with failed mandarins that it sometimes feels like flunking the imperial exam is a pre-requisite. And Pu Songling (1640 – 1715) is a chief among these frustrated scribes.

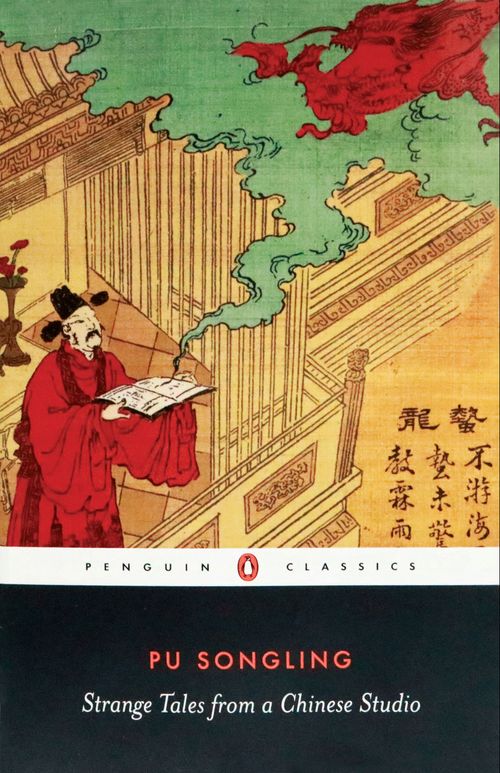

Pu’s early Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) anthology Liaozhai Zhiyi, in English usually titled Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (《聊斋志异》) are preeminent in China’s zhiguai xiaoshuo, a genre of very short classical Chinese stories loosely translated as “miraculous tales”—and miraculous they are.

Pu creates a universe where, as the title suggests, strange things happen. Men are reincarnated as animals, but with enough human memory to avoid eating their own excrement; canine blood is flicked upon invisible phantoms to reveal their whereabouts; lonely women fornicate with lusty dogs when their husbands are away; hallucinating mandarins couple with tree trunks only for their penises to be stung by angry scorpions; the hungry chew on snake heads while the tails wriggle from their mouths like reptilian spaghetti; fox spirits disguised as beautiful women enchant men, making constant love to them until they are dead husks devoid of life force; insect-sized humans hold mournful funerals in empty courtyards; the lovesick jump through temple murals to ravish Buddhist apsaras; people repeatedly die, come back to life, and die again; and lies become truth, and truth becomes lies.

If Pu’s stories sound like the stuff of breathless wild abandon, they are not. The brilliance of Strange Tales is not so much in flights of imagination, though there are plenty of those, but in the controlled and measured style in which they are told. Rather than the flowery baroque style you might imagine from what are essentially ghost stories, each tale is presented more in the manner of an accountant carefully recording figures in a ledger, almost emotionlessly. Gregor Samsa’s utter coolness at being transformed into a cockroach come to mind. And Kafka is a good reference point as he reportedly described Pu’s stories as “exquisite,” and it is clear to see how a literary thread, though a thin one, links the two failed bureaucrats. It is not a surprise that masters of the short story praise of Pu’s work. Jorge Luis Borges was a fan, and both writers wrote short, crystalline tales about myths, legends, and strange beasts, while blurring the real and the imagined. Like Borges, Pu’s laconic, matter-of-fact storytelling is precisely what makes his stories so strange.

The measured tones of the tales can discombobulate. We are often presented a complex story, involving all manner of shocking supernatural events, only for a tale to finish abruptly without fanfare in a brusque sentence absent of comment or grandiosity: “Song wrote a short account of his experience, but alas…it was lost. I have given the gist of it.”

Or, “The magistrate provided him with a written certificate of the facts, and an allowance for his journey home.”

Or, “After six months he made a recovery.”

Initially such endings are unsatisfying; it can feel that Pu has not concluded his stories adequately, that there must be something more to them, that the absurdity of his tales has not been given full space for consideration. But these are Strange Tales and this is how Pu tells them. The brisk endings to the tales soon become addictive, their terse finality leaving the reader slightly confused, yet wanting more.

Few modern readers would take Pu’s stories as anything other than fiction, but at the time it was written, things were often different. Historical figures and events, often battles that took place in the previous dynasty, are dropped into the stories. Many of Pu’s contemporaries, educated or otherwise, would fully have believed in ghosts and spirits, and seen the tales as retellings of events partly, if not completely, true. Perhaps, a few superstitious readers will feel the same today.

The Penguin Classics (2006) edition translated by John Minford is a particularly fine one. We are given 104 of Pu’s stories (out of 500 in the original). Though they usually only run between a paragraph and two pages long, the book also contains an excellent introduction, a short glossary of uncommon terms, and explanatory footnotes to almost every story. For those that want context to Pu’s work, this edition is an excellent starting point.

One of the joys of Minford’s translations is that they attempt to stay true to the original text and avoids some of what he calls “bowdlerizations” to the text. Victorian-era editions of the work bowed to the moral constraints of their times, and some of Pu’s more shocking passages, of which there are quite a few, were either neglected or completely re-written. A man that originally ravished a beautiful female ghost instead sits down to have a cup of tea and a charming chat. This is not to say Minford’s tales are particularly graphic but, as with most good literature, there are more than a few passages not for the faint-hearted. Pu likes to get into the nitty-gritty quickly, though always in his hallmark matter-of-fact style. One story begins:

“There was a merchant of Qingzhou who was much away on business, often for as long as an entire year. He has a white dog at home, and during her husband’s absences his wife encouraged the dog to have sexual relations with her. The dog became quite accustomed to this.”

It is an engaging opener, as is the story’s final line, “This woman is certainly not the only creature with a human visage to have coupled with an animal.”

Understandably, this tale is missing from many of the earlier editions, and some more modern ones, because, as it turns out, some people are not hugely enthused by Qing dynasty bestiality with a bit of torture thrown into the mix, however expertly written.

In the first paragraph of the excellent story “Silkworm,” we are told:

“When our story commences he was 17 years old, but his member was still tiny and shrivelled, no larger than a silkworm. This defect of his was common knowledge, and his marriage prospects were worse than poor.”

Pu was not exaggerating, of course, and later things do not go well for lonely Silkworm: “She lifted the quilt and climbed in beside him, shaking him but eliciting no response. She slipped her hand further down to feel for his member. So crestfallen was she to discover the diminutive dimensions of what he had down there that she promptly withdrew her hand and crept disconsolately out from under the quilt. He heard the sounds of her muffled sobbing and felt pangs of remorse.”

This is certainly not the only couple to have been so frustrated, but it is easy to see why so many earlier editions were bowdlerized, and that some people preferred to avoid Pu’s direct, often humorous, style.

The meaning and morality behind Pu’s tales are not entirely clear, and most are quite a distance from the ethical paint-by-numbers you get from a fabulist such as, say, Aesop. Fox spirits, for example, are by far and away the most common apparitions in the tales, more so than ghosts, and in Asian mythology they are often portrayed as merciless fox demons able to disguise themselves as women who using great cunning to seduce men. These men in turn become addicted to making love to the fox women, lose all their vital energy, and die, leaving the fox-spirit greatly strengthened. Indeed, ancient Chinese Daoists would go to great lengths to avoid such a fate. Pu has plenty of stories like this, but his fox-spirits are often considerably more wise and kind than the demonic succubi of myth, at times going to great lengths to save humans from their own foolishness, even dying for them.

On many occasions a fox spirit will make considerable efforts to befriend and care for the human wife of one of her lovers. Pu’s treatment of the fox spirit is rarely one-sided, and it is the same for ghosts and even monsters. Instead, many of the tales are clearly aimed to take on the folly of men, not demons, but it is never overdone or preachy. It is clear Pu has with a number of the problems with many of the issued faced in his day, be they trivial or large: the unfairness of the feudal system, corruption in the imperial examinations, difficulty with dealing with complex women. But the message is never obvious, his attacks veiled and worn lightly. The strange stories resist any attempt to lecture the reader, instead gently hinting, and poking and getting inside his head in the strangest of ways.

Strange Tales has made its mark on the literary canon: precise Chinese tales of perfect poise and polish, not a single word wasted. Pu’s universe is both repetitive and diverse, imaginative and humdrum, erotic yet unadorned, each story a sip of a very special vintage, which, as before, will no doubt be deservingly enjoyed for the next 300 years or more.

Strange Tales Indeed is a story from our issue, “Wildest Fantasy.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.