Offensive portrayals of Chinese and China in Hollywood

As Black Lives Matter protests sweep across the US and many other countries around the world, the business, marketing, and arts communities have begun to reevaluate racist messaging perpetuated in their products.

American brand Aunt Jemima is abandoning its name and logo, which allude to the “mammy” stereotype of a black woman who is content serving her white slavers. Colgate’s Darlie toothpaste, originally founded and still popular in China, is “reviewing” its infamous blackface logo. 1930s Hollywood blockbuster Gone With the Wind was temporarily removed from HBO’s streaming service due to its racist stereotypes and whitewashing of the horrors of slavery.

Representations of East Asians in American film and theater have also long offered racist caricatures, rather than authentic depictions of the diverse peoples and cultures of the continent. From offensive “yellowface”—where white actors yellow their skin and tape their eyelids to appear “Asian”—to schlocky accents to Orientalist portrayals of Asian females as submissive sexual conquests for white males, East Asian roles in American media have tended to be one-note portrayals focusing on the geekiness, deviousness, mysteriousness, and general “otherness” of Asians. Racially discriminatory wage gaps and casting decisions in the entertainment industry are also wider problems that still need to be addressed.

The following is an incomplete list of TV shows, films, and plays with Chinese characters that the industry may consider “canceling,” or at least providing with a trigger warning, due to sinophobia and Orientalism.

Editor’s note: This piece is limited to the portrayals of characters explicitly identified as Chinese or diaspora Chinese in the work. However, it recognizes that these works exist in a wider cultural, political, and social context of anti-Asian discrimination, and that similar problems are present in other works featuring non-Chinese Asian characters such as Madame Butterfly, Miss Saigon, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and more.

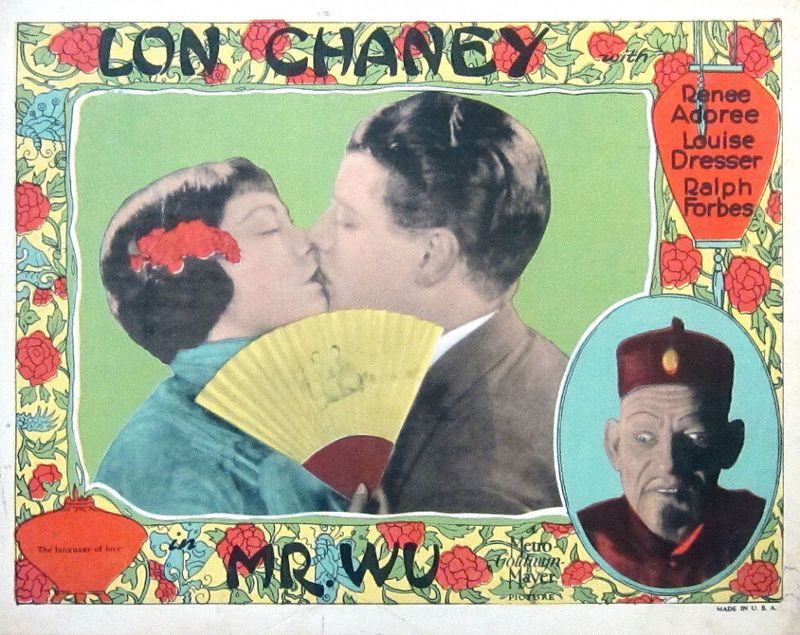

Mr. Wu (1927)

Mr. Wu (1927) – (Wikimedia Commons)

Mandarin Wu is an old-fashioned man raised according to the ancient traditions of strict authoritarianism. He arranges a marriage between beautiful daughter, Nang Ping, and a man whom she had never seen before, but Nang Ping falls in love with a dashing British visitor, Basil Gregory. When Basil must return to Britain with his family, Nang Ping finds out she is pregnant. Mr. Wu consults ancient Chinese texts, which say he must avenge his daughter’s “dishonor” by taking her life. He then tricks the Gregorys to visit his home, where he imprisons Basil and his sister.

This silent movie checks all the boxes of portraying Chinese as backwards, conniving, and cruel, in contrast to the supposedly more innocent and reasonable British visitors. It was adapted form a stage play that opened in London in 1913 and New York the following year. The male and female lead actors in both productions were white. Lon Chaney, who played as Mr. Wu in the film, used fishskin to fashion an Oriental cast to his eyes.

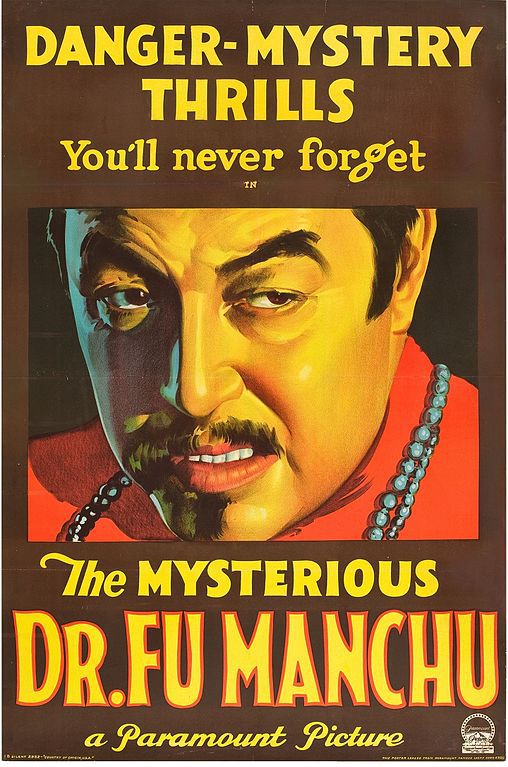

Fu Manchu (1929)

The Mysterious Dr Fu Manchu (1929) – (Wikimedia Commons)

The character of Fu Manchu made his American film debut in The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu. He is the fictional villain of a series of novels by the English author Sax Rohmer, written during the first half of the 20th century. Rohmer wrote 14 novels concerning the villain, and six of the 15 movies were made based on those books, as well as a TV series, several comic strips, and radio shows. The imagery of “Orientals” invading Western nations became the foundation of the commercial success of this series.

As a supervillain, Dr. Fu is involved in crimes such as drug dealing and “white slavery.” His plots are carried out using mysterious methods, including poisonous animals and natural chemicals. He uses torture and other gruesome tactics to dispose of his enemies. He and his criminal organization want to take over the world and restore China to its ancient glory, as well as to rout fascist dictators and then halt the spread of communism for his own selfish reasons.

After the release of the film adaptation of The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), which featured the Chinese villain telling an assembled group of “Asians” (consisting of caricatured Indians, Persians, and Arabs) that they must “kill the white man and take his women,” the Chinese embassy in Washington DC issued a formal complaint against the film. The US Department of State banned the franchise in 1940, as China was an American ally during World War II. The re-release of The Mask of Fu Manchu in 1972 was met with protest from the Japanese American Citizens League, who stated that “the movie was offensive and demeaning to Asian Americans.”

None of the movies or TV shows stars an Asian actor as Dr. Fu, and the character sparked numerous accusations of racism and Orientalism, from his fiendish design to his faux Chinese name. The character has become a byword for the “yellow peril” discourse, which states that East Asians are an existential threat to the Western world.

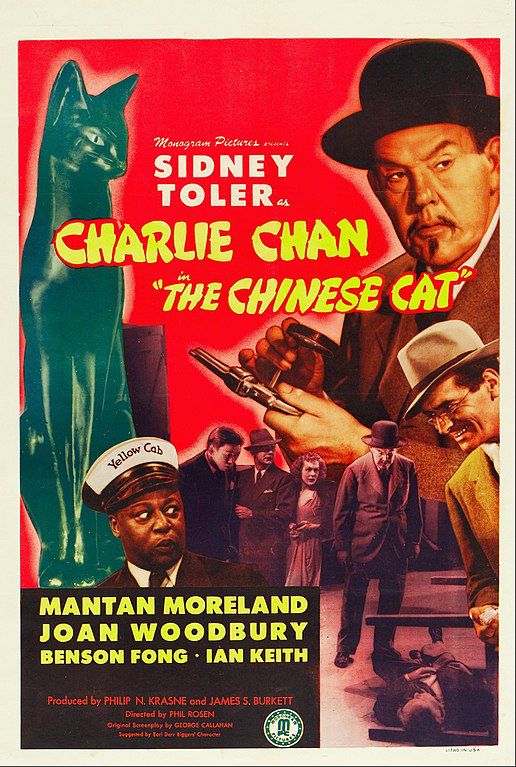

Charlie Chan (1930 – 1940)

The Chinese Cat (1944) – (Wikimedia Commons)

Charlie Chan is a fictional Honolulu police detective of Chinese decent created by author Earl Derr Biggers for a series of mystery novels, loosely based on the real-life Chinese-Hawaiian detective Chang Apana. Chan first appeared in the book The House Without a Key, and the series continued with six books in total. Five of the books were later adapted into films, and the character eventually appeared in more than 50 films, as well as radio shows, comic strips, animation, and even board games.

Chan is an attractive character who is portrayed as intelligent, heroic, benevolent, and honorable, and was conceived of as an alternative to the “yellow peril” stereotype represented by Fu Manchu. Many stories feature Chan traveling the world and solving mysteries using his wit, reasoning, and logic.

While some found the character a positive role model of Asian Americans in early 20th century Hollywood, others point out Chan is still a stereotype. In Up from the Vault: Rare Thrillers of the 1920s and 1930s, John T. Soister argues that Chan is “sufficiently accommodating in personality…unthreatening in demeanor…and removed from his Asian homeland…to quell any underlying xenophobia.” The movies were also severely whitewashed, using white actors in yellowface to impersonate the heavily accented detective. Critic Huang Guiyou stated in his book The Columbia Guide to Asian American Literature Since 1945 that Chan “embodies the stereotypes of Chinese Americans, particularly of males: smart, subservient, effeminate”—similar to today’s “model minority” stereotype.

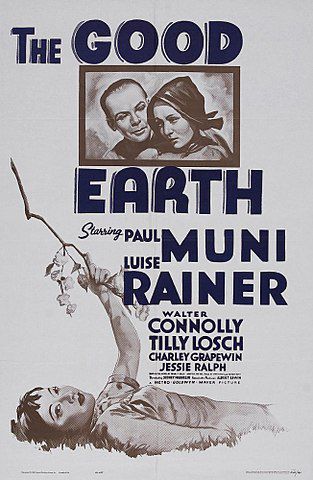

The Good Earth (1937)

The Good Earth (1937) – (Wikimedia Commons)

This movie, based on the 1931 novel of the same name by Nobel Prize-winning author Pearl S. Buck, depicts the rise and fall in the fortunes of poor farmer Wang Lun and his long-suffering wife O-Lan. The film received positive reviews, winning Academy Awards for Best Actress and Best Cinematography. However, all of the main roles in the film were played by white actors in yellowface, including the Oscar-winning role of O-Lan.

Anna May Wong, who is considered to be Hollywood’s first Chinese-American movie star, had lost out the role to white actress Luise Rainer due to anti-miscegenation rules in the Hays Code, which prohibited her from playing the on-screen love interest of the white actor already cast as Wang Lun. Instead, Wong was offered to test for the part of Lotus, the seductive, conniving courtesan. “If you let me play O-Lan, I’ll be very glad. But you’re asking me—with Chinese blood—to do the only unsympathetic role in the picture, featuring an all-American cast portraying Chinese characters,” she reportedly told the studio, refusing the role.

In Netflix’s fictional miniseries Hollywood, Wong, played by Michelle Krusiec, appears as a character in the second episode talking about her experience as a Chinese American in Hollywood. “They don’t want a leading lady who looks like me…You need proof? My entire career. Oversexed, opium-addled courtesans, dangerously exotic Far Eastern temptresses—that’s what they wanted to see from someone who looks like me.” Wong spent most of her career playing these stereotypical roles (including in 1927’s Mr. Wu), and died of a heart attack before she could make her big-screen comeback in 1961’s adaptation of Flower Drum Song, a musical set in San Francisco’s Chinatown with a mostly Asian-American cast.

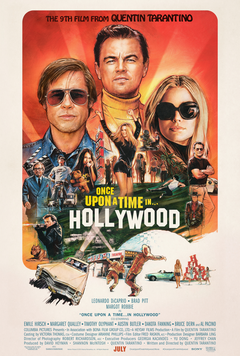

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) – (Sony Pictures Releasing/fair use)

Quentin Tarantino’s ambitious film pays homage to Hollywood in the 1960s, and fictionalizes the lives of film stars from the era. Among them is Bruce Lee, one of the most influential martial artists of all time, and likely the biggest Chinese pop culture icon in the US in the 20th century.

However, Lee’s daughter Shannon described her father’s character in the movie as “an arrogant asshole who was full of hot air,” while Lee’s wife described the portrayal as “insultingly ‘Chinesey.'” In the film, Lee’s character is played for laughs. He insults his white opponent, who imitates his kung fu sounds and then easily beats him. According to Shannon Lee, this disrespectful portrayal recalls “the way that white Hollywood treated [Bruce Lee] in the 1960s,” when he struggled with typecasting as an Asian actor, and would be challenged by strangers in public to fight.

Though the movie was scheduled to premier in China on October 25, 2019, it was never shown in theaters. Shannon Lee had reportedly complained to China’s National Film Administration over the portrayal of Bruce Lee, but there is no official explanation given for why the film was banned.

Should these films, plays, and shows then be canceled? According to New York Times opinion writer Viet Thanh Nguyen, this is not the real question. Rather, censorship and cancellation do little to address the inequities of Broadway and Hollywood, which should strive to highlight real Asian and Asian American experiences and creators of Asian descent. Acclaimed works like The Farewell have shown there is a market for stories about real Chinese people—let’s hope the lesson sticks.