China’s growing presence in Hollywood sci-fi movies

China may be one of Hollywood’s hottest foreign markets, but only 34 foreign films are allowed to enter its lucrative box office any given year, causing studios to trip over each other to appeal to the Chinese consumer.

As kung fu legend Jackie Chan noted, “When China was not the market, you just followed the American way. But these days, they ask me, ‘Do you think the China audience will like it?’ All the writers, producers—they think about China. Now China is the center of everything.”

Indeed, the Chinese box office has been the make-or-break point for many Hollywood blockbusters. Now You See Me 2, a sequel about a ragtag group of stage magicians released in June 2016, made far more money in China (97,115,220 USD) than the US (64,600,802 USD). As the Global Times reported, the film’s success was made possible by the addition of Chinese elements: the director of the sequel, Jon Chu, is Chinese-American; a substantial part of the movie took place in Macau; and Taiwanese pop star Jay Chou joined the cast as a magic shop owner.

Another example is Pacific Rim, a sci-fi action movie released in 2013 featuring a coalition of robots that protect the world from alien attacks. The Chinese-engineered robot, Crimson Typhoon, gained massive popularity in China—helping the film garner almost 112 million USD at the Chinese box office; by contrast, the movie only made 101 USD million at the United States box office.

Another way to ensure access to the Chinese market is by indirectly appealing to Beijing’s sensibilities by portraying China in a positive light. The 2016 release Arrival, starring Amy Adams, did just that. The movie tells the story of a linguist who learns the visually circular-shaped language of recently-arrived aliens and, in turn, is given the ability to time travel. When a miscommunication causes world leaders to consider shooting the aliens, the protagonist travels in time to convince a Chinese general to choose peace—and the rest of the world follows suit.

Another popular market entry tactic, honed by recent Hollywood blockbusters, is to feature China’s burgeoning space program.

In reality, China’s space program is shrouded in secrecy. However, there is no doubt that it is a national priority: President Xi Jinping has stated his desire to see China as a major space power by the 2030s and is supposedly set to triple the amount spent on space exploration, research, and development. The China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) is planning 35 rocket launches in 2018 alone, a number bolstered by its lunar exploration program (named after the Chinese moon goddess Chang’e.)

As China actively develops anti-satellite missiles and space weapons, many are concerned about what this means for the future.

In fact, the “weaponization of outer space” may just lead to this generation’s next space race—between the US and China. By contrast, Hollywood movies are conspicuously devoid of such thorny issues. Instead, these movies optimistically portray the Chinese space program as not only technologically advanced, but also willing to cooperate with the US for the betterment of Mankind.

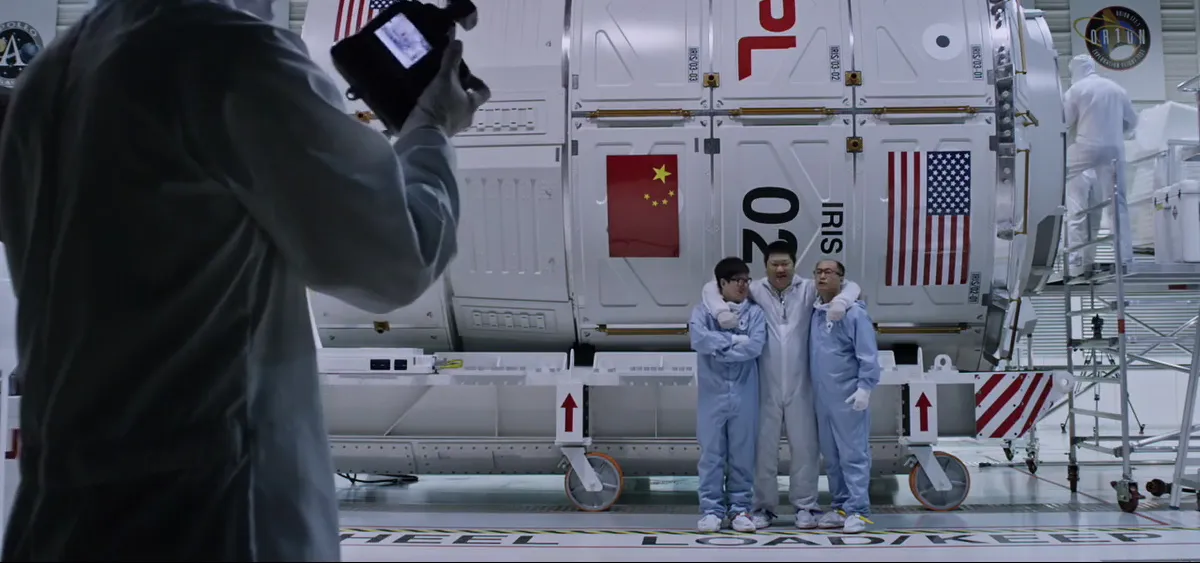

Take The Martian: This 2015 release, starring Matt Damon, concluded with the Chinese “saving the day.” A major plot component involved Beijing providing its classified booster rocket to the Americans to save a stranded American astronaut on Mars. The movie was filled with scenes that presented Chinese officials as competent and empathetic and the country’s space program as enthusiastic partners of the US: Officials were dressed in classy, Western business suits in sleek, modern government offices and a group of Chinese scientists smiled for the media in front of their booster rocket, which featured both the PRC and US flags painted on the side. Following the successful mission, there was the traditional scene of the command center erupting into cheers— not only at NASA, but also in China.

The Martian reaped over USD 50.1 million in the Chinese box office during its opening weekend, a figure that eventually rose to almost USD 95 million. The film was so popular that it prompted a response from Xu Dazhe, the chief of the China National Space Administration: “When I saw the US film The Martian, which envisages China-US cooperation on a Mars rescue mission under emergency circumstances, it shows that our US counterparts very much hope to cooperate with us.”

Chinese officials also praised 2014’s Gravity, which starred Sandra Bullock and George Clooney. The climax also centered around the Chinese space program “saving the day:” A US astronaut takes refuge within the Chinese space station and is able to return to Earth through China’s Shenzhou spaceship. It is of little wonder that the Party chief of the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology Liang Xiaohong called it “the best space film ever.” Zhang Bonan, the chief designer of China’s spaceship program, said that the film was inspiring, and expressed enthusiasm about Hollywood portraying his country’s space program: “It is a good promotion for us.”

China’s movie quota creates unique motivations for Hollywood studios: There is a strong disincentive to cast Chinese as antagonists—for fear that the studio’s movies may be barred from entry in the future. There is also a strong incentive to beat out other movies, not only by appealing directly to the Chinese viewer, but also indirectly to the government. As China’s box office continues to grow and China’s film quotas hold firm, it is possible that more will take this approach in order to ensure market access.