The people’s vegetable that helped northerners get through winter

On December 1, 1949, shortly before Mao Zedong was to depart for Moscow on his first state visit since the PRC’s founding, the Communist Party’s Shandong branch received “extra urgent” summons by telegraph to help the chairman prepare for the momentous journey—by buying him groceries.

It appeared that Mao’s visit was going to coincide with Joseph Stalin’s 70th birthday celebrations, and he had been agonizing over what gifts to give the leader who was then his most valued ally. Eventually, Mao wrote in the telegram, “The central leadership has decided to present big yellow-sprout cabbages, turnips, green onions, and pears from Shandong province as birthday gifts…Please purchase 2,500 kilograms of each within three days…Select the best.”

Known as “baicai” (白菜, literally “white vegetable”) or “big baicai” (大白菜), the Chinese cabbage may seem like an unlikely memento for a foreign state leader. Originated in China at least 6,000 years ago, baicai has long been regarded as the most common and affordable vegetable in the country, as indicated by its nickname, the homophonic “folk vegetable (百姓菜).”

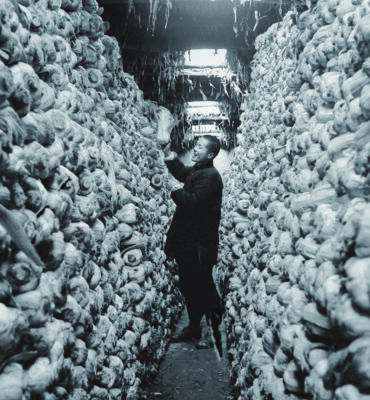

A woman in Shanxi province pickling cabbages in 1959

There were reasons, though, that Mao settled on the humble vegetable as his state gift. First, the Chinese cabbage has a reputation for good taste. Su Dongpo, the renowned poet and gourmand of the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), once wrote that “baicai tastes just like mutton and pork; it is bear paw [an ancient delicacy] grown from the earth.” Poet Fan Chengda, in the same dynasty, praised the taste of Chinese cabbages as “like honeyed lotus root, but even richer.”

Second, in Chinese culture, baicai’s ability to survive cold winters symbolizes integrity. Song scholar Lu Dian wrote: “[Baicai] withers late in the winter, is common in all four seasons, and has the integrity of a pine tree.” The vegetable’s green leaves and white stalks are also often associated with innocence and decency, because the Chinese term for innocence (清白) sounds the same as “green and white” (青白). Cabbages were a favorite subject of well-known 20th century artist Qi Baishi, who titled many of his baicai paintings “清白传家 (Bequeath Integrity to Descendants).”

Beijing residents are the country’s most famous cabbage consumers. In his essay “Hutong Culture,” writer Wang Zengqi states, “If all the cabbages that a Beijinger eats in a lifetime were piled up, it would probably be as tall as the White Pagoda in Beihai Park.”

Beijingers using all kinds of vehicles to transport baicai for winter in 1959

But the most important reason why people consumed Chinese cabbages might be its availability and price. In the early period after the foundation of the PRC, material shortages meant that baicai was practically the only vegetable available in winter, especially in cold northern areas. Beijing native GuoShujing recalled in Xinhua News Agency’s China Album that, “In the old days, all Beijing had in winter was big baicai. It wouldn’t be until April that other vegetables like spinach and round cabbages (圆白菜) came onto the market.”

In Guo’s day, before each winter, northerners would buy hundreds of kilograms of baicai and store them in their cellars, corridors, or even outside their homes throughout the season. If the temperature dropped too low, they would swaddle the vegetable in paper or quilts so that they wouldn’t freeze. These stored baicai were called “冬储大白菜,” meaning “cabbage for winter storage.”

Stored at the proper temperature, baicai can stay fresh for months. When it came time to eat, one could simply strip off the dried outer leaves.

Northerners store a surplus of baicai in their cellars every winter

In the essay “On Eating,” writer Liang Shiqiu recalls, “In Beiping [Beijing], baicai is available all year round. In early winter, peddlers would wheel trolleys, hawking their baicai on the street. Ordinary families often cleaned out a whole trolley in preparation for the rest of winter.”

Under China’s planned economy from 1953 to 1992, this tradition was given a collectivist twist. Cabbages were collected from the farmers and sold to citizens exclusively by the government. Citizens could only buy if they presented a “non-staple food certificate,” which, under China’s grain rationing system, showed how much of a particular good they were allowed to buy.

Every November, to guarantee that people would have vegetables to eat in winter, tens of thousands of workers around the nation, from the departments of transportation, public security, city sanitation, and even meteorology, had to assist in the harvesting and selling of baicai. Beijing once established an “Autumnal Vegetable Command Post,” known colloquially as the “baicai office,” to ensure that all 4 million Beijing residents received their allotted “half-kilogram of baicai per person per day.”

Sun Yulou, a member of the Beijing baicai office, compared the annual baicai allocation to “fighting a battle”: “Even if we count the winter as three months…it’s 200 million kilograms of baicai, and there were 1,100 vegetable stores across the city…all the work needed to be finished within about ten days,” he told China Album. At that time, many state “work units” had unwritten “baicai holidays” to give their employees time to buy cabbages, which often involved lining up at the crack of dawn outside vegetable stores. “When I was young, when it was time to buy baicai, there would be a traffic jam, a very bad one,” Guo told China Album.

Baicai can be stir-fried, boiled, pickled, or made into salad

But fortunately, though baicai was most people’s only vegetable during the winter, it’s an all-purpose food that can be stir-fried, stewed, pickled, and even made into salad or soup. Due to its bland flavor, baicai goes well with most kinds of meat, whether it’s lamb, beef, pork, or chicken. A folk saying praises baicai’s versatility: “百菜不如白菜 (A hundred vegetables are inferior to baicai).” Cabbage-painter Qi has argued: “Peony is the king of flowers; lychee comes first among all the fruits; why isn’t baicai named the king of vegetables?”

Kings do not rule forever, though. After China enacted market reforms, people had access to a more diverse selection of winter vegetables, so baicai no longer dominated northern tables. By the end of the 1980s, there was no longer a vegetable shortage. The baicai harvest saw a bumper year in 1989, but for the first time, demand was slack in Beijing, and local government had to call on citizens to “buy the patriotic vegetable” via newspapers, radio, and TV advertisements in order to offload the baicai surplus.

A people’s commune cafeteria cooking baicai in 1960

As of 1991, sales of baicai are no longer rationed, and more varieties of vegetables have become available, including formerly “exotic” imports like broccoli. The main appeal of baicai these days seems to be its still-low cost: “baicai-priced” has even become a slang term, meaning “dirt cheap.”

But the tradition of purchasing baicai for winter has not completely disappeared. Each November, the markets and supermarkets in Beijing begin to sell baicai as usual, and local consumers are still willing to queue. “The sales are decreasing year by year,” Wang Risheng, manager of a Beijing grain store, lamented to the Beijing Daily recently. “But as long as there are buyers, we will insist on selling.”

Images courtesy of China Album

THREE CLASSIC CABBAGE DISHES

Mustard cabbage rolls

Known for its refreshing taste, this salad-like dish is a must-have on Beijing tables in winter. It’s often served at festival banquets to balance out the greasy taste of meat dishes. While many traditional Beijing dishes are lost to history, mustard cabbage rolls have managed to survive, perhaps because the recipe is so simple: Cut tender Chinese cabbage leaves into sections; steam them with a topping of powdered mustard, salt, sugar and vinegar; and roll them up before serving. As a folk saying goes, it “can both inspire refined scholars and feed starving people in poverty.”

Spicy cabbage

Kimchi, or spicy cabbage, is the iconic food of Korea. But according to Korea’s World Institute of Kimchi, 89.9 percent of the kimchi purchased by South Korean restaurants in 2016 was imported from China. Chinese diners, especially the Chaoxianzu, China’s ethnic Korean minority, also love these salted and fermented cabbages. Though usually served as a side dish, this versatile ingredient can also be stir-fried with pork, put in the middle of hamburgers, or added to soup or hot pot—even instant noodles come in “spicy cabbage” flavor.

Cabbage and meat soup

Chinese cabbage is known for its bland taste, meaning it can be cooked with almost any kind of meat. This Cantonese dish boils the fresh inner leaves of the cabbage in chicken soup along with ham, lean pork, picked eggs, and even edible sandworms. When cooked, the cabbage leaves become tender and fully seasoned, and give the soup a delicate fragrance. Shrimp, scallops, and other seafood can be added to taste.

Images from VCG

King Cabbage is a story from our issue, “Alpine Ambitions.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.