Artist Qiu Zhijie tackles both world and Chinese history at new exhibit

Paper maps may sound antiquated in the digital era, but Qiu Zhijie’s attempt to map the world’s knowledge in his new solo exhibit at Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art is anything but. On display until May 5, “Mappa Mundi” is an exhibit that is overwhelming to both the eyes and the mind—and leaves you feeling small in the vast world.

Although he rose to fame through experimental works in photography and videography (in particular, the 1990s “Tattoo” series, featurng his bare chest painted with Chinese characters), Qiu’s most recent endeavor is mapping.

“Mapping is the best way to tell stories,” he told CNN. While information has become more available with the internet, knowledge itself has become more fragmented and harder to understand. He believes his maps can bridge gaps in people’s cognition to give them a broader perspective.

Qiu’s work are massive in both size and scope

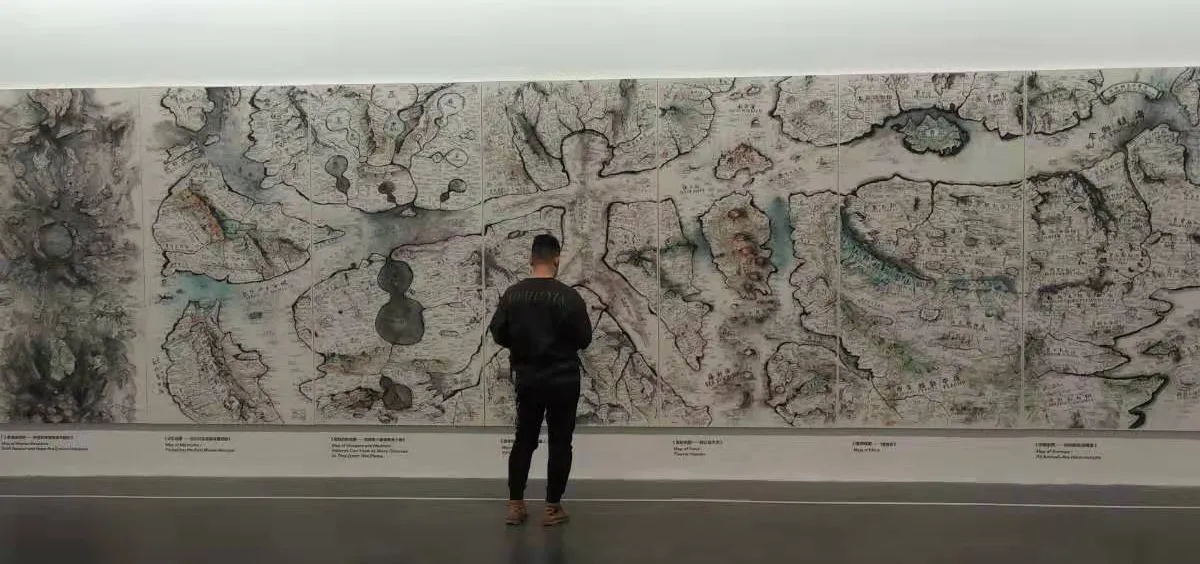

Among the works displayed is his famous Map of Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, commissioned by the Guggenheim in 2017.

Painted in the style of a traditional Chinese ink painting, this massive artwork takes up six panels. From afar, it is surprisingly devoid of color and lacks the typical visual cues which encourage one to get closer. However, the words and the ideas which Qiu puts together while “mapping” draw the viewer in. One can easily get lost in thought, as Qiu attempts to make sense of the chaos of modern China by mapping out the trends, events, and people of the last three decades.

When discussing his process of mapping, Qiu told CNN that a “monumental event… is going to be a peak.” To map the tortuous routes of Chinese art and history during the last few decades, these mountains of uncertainty are broken up by reservoirs of creativity fed by rivers and canals “before joining the ocean of speculation and uncertainty.”

Canals and rails encounter roadblocks in Qiu’s “Map of Art and China and 1989”

Teaching at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Qiu is known as a bit of a radical, and unapologetically explores China’s most controversial modern history in his art. He attacks sensitive subjects head-on, he says, “because if you don’t discuss it, [the students] use VPNs and go see it themselves anyway.”

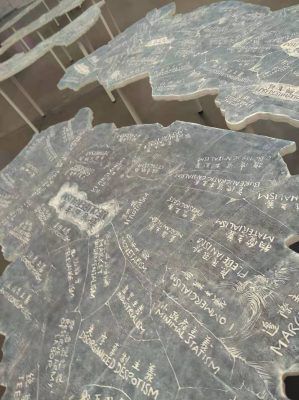

Another moving work is Qiu’s “Isms at the End of the World,” which is made up of 28 “islands” placed at waist-height tables. Viewers can walk around the islands, which are mapped out with competing schools of thought and belief systems. Many debates have raged over these “isms,” yet seeing them all written out, their totality seem so small compared to the universality of the human experience.

Islands of “Isms” are spread throughout an open room at Beijing’s UCCA

Perhaps what is most refreshing is how the exhibit is able to balance both Chinese and Western history in providing its perspective of the world. All of Qiu’s works are mapped in both English and Mandarin Chinese. Additionally, his “Map of Maps” (created for the Singaporean Biennale) delves into both Chinese and the Western ages of exploration, drawing comparisons between Zheng He and Christopher Columbus, as well as the maritime monsters that haunted the dreams of all sailors, regardless of nationality.

“Map of Maps” attempts to tell the story of exploration and discovery – from both a Chinese and western perspective

Photos by Emily Conrad