The country that invented tea struggles to export it—and the culture it represents

“Our country’s tea industry is big, but not strong,” lamented Tang Ke, the Director of the Market Economy and Information Department at the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture, in an interview with agricultural news portal 1Nongjing. “There are lots of reasons for this, but one of the important ones is that we lack a strong brand.”

He goes on to explain that although China exports a lot of tea leaves, “because our brands are weak, the export price is low.”

In country whose economy embodies the concept of rapid development, China’s tea industry stands out as the lethargic player, lagging behind the food safety standards set by the rest of the world said Greenpeace.

Chinese tea companies produced more than 2.4 million tons of tea leaves in 2016, amounting to over 40 percent of the world’s total output. However according to 1Nongjing, because the plantations nestled in the rolling hills by the Yangtze River and the verdant mountains of the Southwest are small and labor intensive, they are only 40 percent as efficient as tea farms in India.

Most provincial tea plantations also lack the expertise to process—and add value to—their product; in fact, only six percent of tea plantations create a finished product. It is thought that more than half of China’s estimated 66,000 tea producers export tea as a raw product, and more than 90 percent of tea plantations make less than 5 million yuan a year ($73,500).

Tang’s assessment rings true: “Big, but not strong.”

Voices agreeing with Tang echo from every corner of the industry. Hu Guoxiong, the incumbent West Lake Longjing Tea Master Roaster from Hangzhou’s famous tea terraces, told 1Nongjing, “We need to establish brands…to take Chinese tea’s traditional culture, its history, and incorporate it with cups of tea across the world.”

But the tea leaves are starting to spell out a different future. In January of this year, the Ministry of Agriculture launched a scheme to “improve the efficiency and competitiveness” of Chinese agriculture. This policy, known as “2017: Year of Agricultural Brands Promotion,” promises “deep supply-side structural reform” according to China Daily.

The plan focuses on two areas in particular: improving the quality of tea products, and establishing brands and marketing strategies that can help the “large crowd of small Chinese brands” compete with “Western giants,” Dang Guoying, a researcher with the Rural Development Institute at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told China Daily.

The ministry’s approach seems to be working. To ensure the zero increase in the use of chemical products, the scheme provides all plantations that want them with free or subsided organic pesticides and fertilizers. Not only does this add value to the tea by allowing it to be exported as an organic product, but it is also protects the future of the tea industry by combating the soil acidification of plantations caused by chemical fertilizers. Local governments have also been encouraged to give rural start-ups tax benefits, financing, and insurance.

The policy outlines how larger farms can be helped, too. New courses in agricultural management, rural planning, and house design are being written up for institutions of higher learning. Recent employment drives have also encouraged university graduates and entrepreneurs to consider piloting technological and managerial innovation in rural areas. Although these benefits have yet to come to fruition, they demonstrate a longer term commitment to rural development.

Along with improvements in the quality and value of tea products, the branding and promotional strategies that are bringing them to market are also modernising. In April, a spokesperson for the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) announced the policy’s vision for the future—the ‘Internet Plus’ model.

Song Cheongmin, a macroeconomic management official for the NDRC, told China Daily that China “has long passed the time where farmers only toiled on their land. In our era, ‘Internet Plus’ must be highlighted.” The impenetrable ‘buzzword’ means that farmers and tea companies will get help from mainstream and online media to produce brand-building adverts.

Dang added that the top priority was “to find a carrier to hold the brand.” One company vying to be this flag carrier is Xiao Guan Tea. Established only two years ago, the luxury brand has already launched a flagship store in Beijing and published several promotional videos, the most recent of which, “Xiao Guan Tea’s Search for Tea,”almost resembles a piece of art more than an advert.

In May, more than 40 Chinese companies showcased their products at the “Premium Agricultural Brands of China” exhibition at the International Agriculture Fair in Serbia. As China’s “One Belt One Road” initiative gathers momentum, the government hopes that agricultural brands will be just one of the many high quality, value-added Chinese cultural exports.

However, not all in the industry are as optimistic about the future.

“I’m scared of the development—it’s too fast,” a man surnamed Wang, owner of a small traditional tea house in Beijing, tells TWOC.

Wang’s attitude towards the agricultural brands promotion policy is complicated. He welcomes the protections it brings to tea plantations and farmers, as well as the standardized food labeling and safety procedures brought in to make Chinese exports reach EU standards; but he also has misconceptions about how well tea can be exported to foreign markets.

“It can be done—of course it can be done—but it’s a difficult problem.” Wang says, looking around his tea house.

“If you export tea—perhaps in a box, perhaps in a bag—you sell the tea abroad; the consumer boils some water and brews a pot or a cup of tea. They drink it and then throw it away. That’s not Chinese tea, it’s a drink,” he says.

“I worry that foreigners may misconstrue what Chinese tea is really about. They might think ‘Oh, so this is what Chinese tea is really like!’ [even] after drinking a high-quality, branded exported product, but that’s not true.”

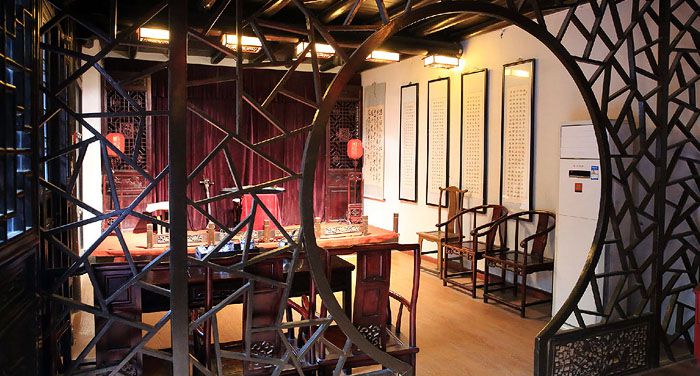

Wang’s earnestness to share tea culture with the world is palpable. “Tea is a cultural vehicle,” he explains, “it’s the table our cups our sitting on, the craftsmanship of the joinery that holds it together; it’s the woven bamboo mat lying on the surface of the wood. It’s the calligraphy hanging on the wall, the conversation we’re having over this pot of pu’er.”

“Tea culture is the friends I’ve met through tea (cháyǒu 茶友), the acquaintances who buy tea from me and then become friends with whom I do things that have no relationship with tea at all,” he adds. “Tea is something that brings people together (cháyuán 茶缘); this is true Chinese tea.”

His forecast for the future of Chinese tea export is not all doom and gloom—he has his own solution to offer. “For Chinese tea to be exported properly—for Chinese tea culture to be exported properly—you need communication. You need people who love drinking tea to meet, to talk to each other, to talk over pots of tea,” he says.

“When governments and high-level officials manage exports and control how imports work, this is not what they talk about, because they’re not ‘tea people’—they’re politicians. I think it’s possible, I think true Chinese tea will be exported in the future, but I don’t know when.”