On-camera student suicides bring visibility to power abuse by parents and educators

Two recent teen suicides, both caught on camera, have opened widespread discussion on teaching methods, generational conflicts, and abuse of power in a country that places enormous store on the authority of parents and educators.

In April, a 17-year-old boy was caught on security footage leaping out of his mother’s car on Shanghai’s Lupu Bridge, then jumping into the Huangpu River. This raised an outcry when the mother admitted that she’d been upbraiding her son over his behavior in school.

The public consensus was that the mother’s car lecture had been the straw that broke the camel’s back, presumably coming after a long history of meddling in her son’s affairs. (A few netizens took the opportunity to accuse today’s youngsters of being too soft to handle parental criticism)

The tragedy soon drew comparisons to another incident five days later, in which a middle-school student live-streamed his own suicide—drinking pesticide, tearing out the pages from his textbook, and declaring, “I’m dying. It’s all [my teacher] Yang Xiaorong’s fault.”

The boy had argued with his parents over a conflict with his classmates and his scores in a recent exam; the local education bureau has since cleared the school of any blame.

As for the court of public opinion, while some again blamed a culture of spoiled single children, younger netizens sympathized with the boy’s reaction, with many recalling their own brushes with self-harm and suicide due to pressure from teachers and overbearing parents.

Anger at the latter has been prevalent online for well over a decade, with many adult children of “ultra-conservative, ignorant, and unreasonable parents” forming “anti-parent” groups on sites like Douban to discuss how to resist and reform such child-rearing methods.

As China’s increasingly worldly millennials become parents themselves, many are dismayed to see the same patterns of abuse and manipulation played out by those of their own generation, swaying much of the online commentary in favor of the teens. “Parents should adopt smart methods to help them establish a variety of social and world connections. Let them understand how colorful life is through diverse activities,” one father told the Global Times.

Topics such as suicide and death have long been taboo in Chinese society, but the shocking and public nature of a few recent events have forced some of these issues out into the open. The 2018 suicide Tao Chongyuan, a 26-year-old chemistry student at the Wuhan University of Technology, was attributed to a toxic relationship with his graduate supervisor, and led to a vigorous debate on China’s ancient reverence for teachers.

Tao’s case is hardly unique in China’s troubled higher education sector, but stayed in the headlines due to a media campaign spearheaded by Tao’s sister, and a civil suit which resulted in Tao’s abuser being banned from supervising graduate students and forced to pay the family compensation.

In a WeChat essay published on the incident’s one-year anniversary, journalist Ge Jianan found that Tao’s suffering, though immense, had been largely ignored by those around him while he was alive: “He was insecure, anxious, and lonely…a victim who used to be around but unseen in most people’s eyes.” Many hope that such cases will serve to educate teachers and parents about the power they may unwittingly wield, and the extremes to which some teens will go to escape it.

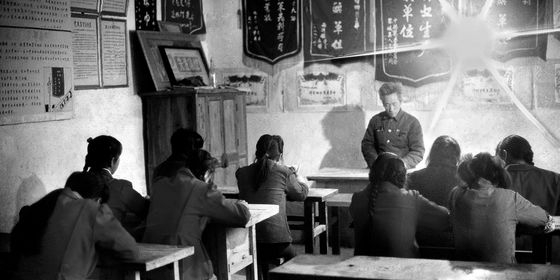

Cover image from VCG