Banished literati who made Hainan’s history

In 1097, when 60-year-old poet and official Su Dongpo (苏东坡) arrived at Danzhou, Hainan province, he had an inkling that it might be the last stop of his life. A far cry from today’s tourist attraction, Hainan Island in Su’s time was a wild outpost of the Chinese empire.

While the idea of such a place would be more than enough to scare away most people, Su had no choice but to make a home for himself in the jungle. Accused of defamation by a political rival, Su was demoted and exiled to the desolate island. In his day, this was said to be a punishment only slightly less severe than taking one’s life.

With sadness and fear, Su wrote in a letter to a friend: “Going to this savage island at such an old age, I am afraid I can’t return within my lifetime. When I left my eldest son this spring, I arranged my funeral and everything afterward.”

Su’s hunch was almost correct—he died on his way back to the north, when he was pardoned and summoned home three years later. What he hadn’t expected, though, was that in the interim, he would bring about many dramatic changes to the island, and would eventually, reluctantly, fall in love with his temporary home.

The conditions on the island were as bad as Su had expected. In a letter he wrote to his friend Cheng Tianmou (程天侔), Su described the hardships he was faced with: “Here I have no meat for food, no medicine to cure illness, no room to live in, no friends to see, no coal for the winter, and no cool spring water for summer.” But Su didn’t surrender to this bleak reality. Ten days after he arrived in Haikou, Su gave his first alleged gift to the island. At that time, Hainanese didn’t have sufficient potable water and were often forced to drink salty, stagnant water. Su knew that to survive there, he would have to find healthy drinking water for himself and the local people.

Statues of Su Dongpo can be found in his former places of residence across the country, including this renowned one at the Dongpo Academy in Danzhou (VCG)

After careful research, Su found two springs in the northwestern corner of the city. One of these springs flowed with clear, sweet water, and Su immediately called the residents together and taught them where to dig wells. From that point on, all locals had clean water to drink. The spring was later named Fusu Spring (浮粟泉), and is still in use today within the Temple of the Five Lords (五公祠) in Haikou.

Food was another problem for Su. Agriculture was undeveloped in Hainan, and local people lived by hunting. Their cuisine appalled the fine literatus, who even complained in a poem about the local’s “bizarre” eating habits: “Pork can only be seen every five days, and chicken every 10 days. Local people eat potato and taro at every meal and recommend smoked rats and roasted bats. In the past I threw up when I heard they ate infant mice with sugar, but now I am a little more used to the custom and can eat some toad…” It’s said that Su tried to teach local people to cultivate the land and plant grains. He introduced advanced farming techniques to Hainan’s farmers, and rewarded them with six poems to “encourage farming,” which are still well-known today.

Considering himself quite the foodie, Su still managed to find some edible delicacies in Hainan. The first was the oyster. After trying boiled and roasted oyster, Su deemed it a delicious food that he “had never tasted before,” and jokingly warned his son Su Guo (苏过), who accompanied him in exile, not to tell his friends in the north, in case they descend upon Hainan to snatch up all the oysters for themselves. Another favorite dish was a porridge invented either by Su or his son. Taro and rice were boiled together to make a thick stew, which Su named “jade rice porridge” (玉糁羹), praising it as food “that shouldn’t be found in the mortal world.” Today, in many restaurants in Hainan, this porridge is still on the menu.

Zaijiu Pavilion over a lotus pond in the Dongpo Academy in Danzhou, where Su Dongpo once fed birds and fished (VCG)

When it came to medicine and healing, the local people of Hainan were said to be highly superstitious, believing that praying at the temple or sacrificing cattle to gods would stave off illness. As a result of such customs, many people lost both their livestock and their lives. Su went through great efforts to collect medical herbs and write lengthy medical notes, even finding new herbs and useful medicine native to Hainan.

While he clearly advanced Hainan in many ways, Su’s largest contribution was in the field of education. Before Su arrived, no Hainan scholar had ever succeeded in passing the imperial civil service examination.

The government provided no housing for Su; he resided in a small house built of areca wood, which he constructed with the help of local residents. Su named his house Areca Hut (槟榔庵). A local official named Zhang Zhong and a scholar named Li Ziyun sympathized with Su, and built him another house near Li’s own residence. This house was named Zaijiu Hall (载酒堂). Within his new abode, Su gave lectures to the local people, and promoted the culture of the mainland.

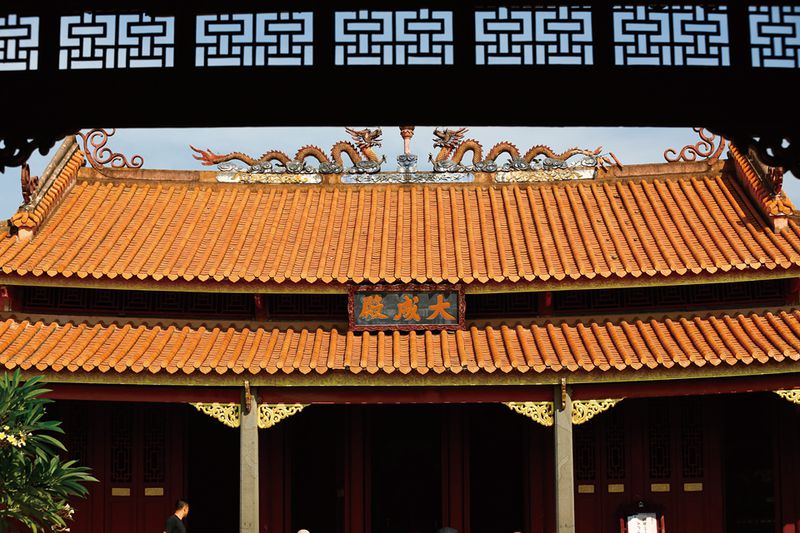

Dacheng Hall is the main hall of the Temple of Confucius at Yazhou, also called the Yacheng Academy (Photo by Zhong Ming)

In the three years Su lived in Danzhou, a new atmosphere of study was established. Years later, Su’s student Jiang Tangzuo (姜唐佐) became Hainan’s first juren (举人), the title granted to scholars who succeed in the provincial civil service exams. Another student, Fu Que (符确), became Hainan’s first jinshi (进士), the title held by those who passed the imperial exam in the capital, who were qualified to hold a government post. From the Song dynasty (960 – 1279) to the following Yuan (1206 – 1368), Ming (1368 – 1644), and Qing (1616 – 1911) dynasties, Hainan produced 767 juren and 97 jinshi, including the famous Ming official Hai Rui (海瑞), who is respected as a symbol of incorruptibility and integrity in Chinese history. Hai’s former residence in Qiongshan district, Haikou, is now a tourist attraction. During the Qing dynasty, Zaijiu Hall was renamed Dongpo Academy (东坡书院).

Over the years, the academy was enlarged and renovated several times, and is now under government protection as a historical and cultural site. Every year, a large number of tourists visit Danzhou, and the Dongpo Academy is one site they never miss. The academy faces south with a beautiful, traditional door. In the courtyard, there is a pond with a bridge leading to the Zaijiu Pavilion (载酒亭), which is covered with green tiles. Near the pavilion is Zaijiu Hall, which houses 13 tablets with inscriptions written by famous people from history. At the rear wall of the hall, there are two marble stone inscriptions. One is a verse by Song Lian (宋濂), a poet of the Ming dynasty, and the other is a picture of Su Dongpo, painted by the Ming painter Tang Yin (唐寅). Finally, one can wander into the Great Hall to view statues of Su and his son, as well as exhibits of paintings and poems by Su.

The Dongpo Academy is not the only location in Hainan set up to commemorate Su Dongpo. The Temple of Five Lords in the city of Haikou is an ancient architectural complex dedicated to historical figures who had ties to Hainan. On the east of the complex is Lord Su’s Temple (苏公祠), which hosts the Fusu Spring. The temple was built in 1617 as a location from which people can worship Su Dongpo and Su Guo. There is also a memorial tablet for Su’s student, Jiang Tangzuo.

First built in the 10th century, the Yacheng Academy combines worship with learning in the tradition of ancient Confucian Temples (Photo by Zhong Ming)

The main part of the complex is the Five Lords’ Hall, a red two-story wooden building constructed during the reign of Emperor Wanli in the Ming dynasty to commemorate five famous officials—Li Deyu (李德裕), Li Gang (李纲), Zhao Ding (赵鼎), Li Guang (李光), and Hu Quan (胡铨)—who, like Su, were also banished to Hainan. Li Deyu was a chancellor in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), who was disliked by Emperor Xuanzong and exiled to Yazhou (崖州), Hainan. The other four were all officials in the Southern Song dynasty (1127 – 1279) who advocated war against the invading Jurchens, and were persecuted by political rivals in favor of appeasement. These days, the hall houses lifelike stone statues of the five officials.

The five disgraced lords and Su Dongpo actually only made up a small part of the island’s exile population. Many highly ranked government officials were forcibly sent to live in the Yazhou district of Sanya during the Tang dynasty. The town was dubbed “The Home of Hermits” (幽人处士家). Li Deyu, one of the “Five Lords,” lived in Bilan village (毕兰村) in Yazhou, which is today’s Baoping village (保平村). The village has maintained many architectural complexes built in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Shuinan (水南村), another village in Yazhou, was the exile home of Song dynasty chancellor Lu Duoxun (卢多逊), and there are still three or four of Lu’s direct descendants allegedly living there.

Other former residents of Yazhou were the monk Jianzhen (鉴真), who was shipwrecked in Hainan while sailing to Japan to promote Buddhism during the Tang dynasty; and Huang Daopo (黄道婆), the “mother of Chinese textiles,” who learned weaving techniques from the Li people and brought them back to the mainland. Today in Yazhou, a popular tourist attraction is the Temple of Confucius, also known as the Yacheng Academy (崖城学宫), which was the highest seat of learning in ancient Yazhou as well as the southernmost Temple of Confucius in China.

Today, Hainan Island is no longer a desolate outpost where exiles are forced to settle. Millions of people flock to the stunning island for their annual vacations, and it is regarded as a paradise for tourism. But history is never forgotten, and the legacies of Su Dongpo, the “Five Lords,” and all the other banished officials have become essential cultural relics, which captivate visitors and encourage them to think about both the past and the future of the land.

Cover image by VCG