Ancient health tips are trending—but are they nourishing or hazardous?

A fear of sudden death was what prompted 29-year-old June (pseudonym) to take interest in the ancient philosophy of “nourishing.” The Shenzhen-based video director had thought nothing of working until the early hours of morning and going on months-long shooting trips, until she heard in the news early this year that young white-collar professionals were suffering obesity, premature baldness, and even cardiac arrest from apparent overwork.

Concerned about her irregular periods, constant acne outbreaks, and deteriorating physical appearance, June tried taking to bed early in order to “live longer, travel to see more of the world, and eat better food.” When insomnia and the nature of her job made this impossible, though, she changed tack: taking vitamins and collagen capsules, buying expensive cosmetics, and visiting a beauty salon and massage clinic once a week in an effort to counterbalance her all-nighters.

June is one of countless millennials spurred by a slew of health care stories to assert their own take on a millennia-old lifestyle. First medically recorded over 2,000 years ago in the Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor, China’s earliest medical text, the idea of yangsheng (养生, “preserving life” or “nourishing life”) is about “obeying the laws of the four seasons and changing temperatures, calming the mind and living in a peaceful surrounding, and balancing yin and yang.”

Yangsheng based on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is still practiced today, mostly by the middle-aged and elderly, who use TCM terms to explain their decisions to avoid “hot”-natured foods such as lychees, longan, and anything fried or spicy, or to drink chrysanthemum tea and Chinese green bean soup to relieve excess yang energy.

A young factory worker watches videos at night while applying a face mask

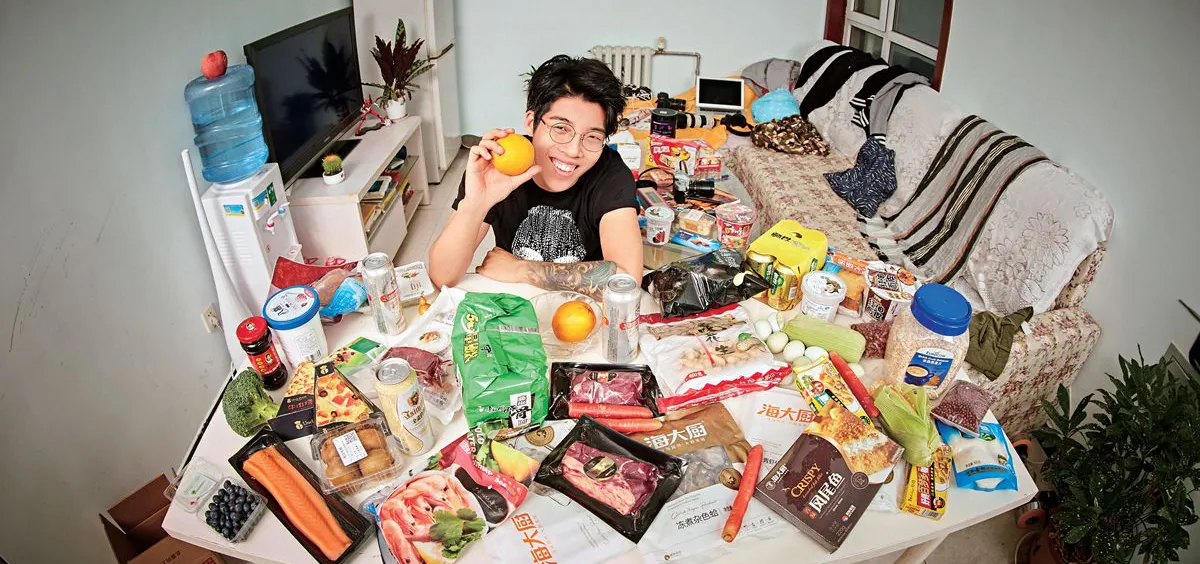

Younger Chinese getting in on the yangsheng game, though, have changed the rules of ancient healthy living to fit with their own lifestyles. Regimens like June’s have been cheekily dubbed “punk yangsheng” (朋克养生), a selective practice of traditional yangsheng advice within a modern, urban schedule, where a desire for better health sits alongside an unwillingness to forgo unhealthy habits. “Confronted with huge social pressures, we all want to live well,” says June. “But sometimes, things are simply out of our control.”

“Many young Chinese care about their health, but they’re unwilling to give up modern enjoyments,” says Gu Zhongyi, a registered dietitian and popular science writer with over 4 million fans on social media. “Young people need to work hard to make money and enjoy life [at the cost of health], then hope to find an instant way to improve their health.” Rather than strict diets and gym visits, “punk yangsheng” youths may use expensive facial masks to compensate for the negative impact of late-night TV marathons, or drink herbal tea to relieve gastrointestinal burdens after a spicy meal.

“[Young] people I know live this way,” June tells TWOC—that is, abusing their health on one hand, and on the other, trying to undo the harm with remedial measures. “[They] drink beers with wolfberries, or an ice-cold drink with a cup of hot water.” (According to TCM, millennial favorites like cold milk tea and iced Coke harm the stomach, spleen, and qi, or vital energy, and can result in menstrual cramps, whereas hot water is considered healthy.)

Food or dietary supplements are among the most popular health kicks for the lazy or overworked. The Chinese data research firm Sootoo Institute’s 2017 “Post-90s Healthcare Report” surveyed the use of health products or supplements, which are defined by Chinese regulations as foods that can help coordinate bodily functions and are beneficial to certain groups for non-treatment purposes. Health products and supplements were rated the third most popular way to keep fit, after going on a diet and taking regular exercise; 21.9 percent of “post-90s” millennials surveyed were currently taking them, and 47.9 percent have tried them.

Few young Chinese have time for regular gym exercise

Searches on the popular social e-commerce app Xiaohongshu produce over 390,000 “health product” diaries and 10,000 supplements, including an extract of grape seed liked by over 140,000 users. The 2018 Blue Book of Health Management, a document compiled by leading academic health institutes, predicts that China’s healthcare market will grow to 180 billion RMB in 2020.

On November 11, 2017, nearly 179 tons of Chinese wolfberries sold out within one hour on e-commerce sites Tmall and Taobao during the “Double Eleven” shopping event. Wolfberries, also known as goji berries, are regarded a popular cure-all with dozens of supposed health functions including improving immunity and liver performance. They are said to go well with most food and drinks—even instant noodles and hot pot. A vacuum flask of wolfberry-infused hot water—previously relegated in the popular imagination to middle-aged men seeking to strengthen the kidneys—is now considered a standard punk antidote for overdoing the beers.

The lifestyle has its skeptics, though, who are disillusioned by the reliance of millennial yangsheng on consumption—and how it has been co-opted by businesses in turn. “Punk yangsheng is superficial,” says Zhu Yujiao, a 32-year-old director of a Shanghai-based advertising company. “It produces little effect except to comfort oneself.”

Fruit and flower teas are touted as healthcare solutions

Zhu speaks from experience, often applying a facial mask after a long day. Though the many promised effects of this skin-nourishing solution haven’t been proven, the market research agency Mintel reports that the facial mask market was worth over 21 billion RMB as of 2017, having grown at a rate of 30 percent per year since 2012.

Meanwhile, the original philosophy of yangsheng—diligently observed by parents and grandparents, who sleep and rise early, and exercise every day—has been inexpertly adopted by those like Zhu, who fear that they are unlikely to suit the vast pressures and demands they face. “I admire other gym-goers, and I could spare time for sports on weekends…but would rather get some extra sleep and watch TV,” said Zhu.

In its 2019 National Health White Paper, medical startup Dingxiang Doctor reported that only about 25 percent of “post-80s” and “post-90s” millennials exercise over three times a week, while 31 percent exercise less than once per month. “The significance of physical activities is commonly recognized, but there are still not many doing them,” the report quotes Dr. Qi Zhengrong of the Beijing Friendship Hospital as saying. Although the paper’s respondents rated the importance of physical activity at an average score of 9.2 out 10, most said they were too busy to do it, or “think ‘I’m still young and a long away from developing health problems,’” said Dr. Qi.

“The post-90s generation has been more accustomed to the Western concepts of taking vitamins and minerals for supplements, and access more modern ideas via entertainment-orientated channels instead of traditional TV and newspapers,” adds the nutritionist Gu, who predicts increasing integration of Chinese and Western notions of popular health in the future. “Some products, such as vitamins and minerals, may be beneficial to people’s health in certain respects, but most functions consumers expect [from health foods], such as preventing chronic disease and prolonging life, have not been proven.”

Gu can understand these kinds of choices. Nevertheless, he hopes to “help people better understand the costs and benefits of each choice, and to be able to enjoy life at the lowest costs.” And while innovations and substitutes purport to reduce the risks of some of our favorite temptations, Gu emphasizes, “The best way to keep healthy is to develop a healthy lifestyle.”

Punk Science is a story from our issue, “The Good Life.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.