Professional “insult” and eating services are trendy—but may have more hype than actual sales

A viral screenshot of a WeChat coversation, advertising “one quarrel in Mandarin for 100 RMB, and money back if you lose,” revived moral and legal scrutiny over China’s thriving “substitution” market over the May Labor Day holiday.

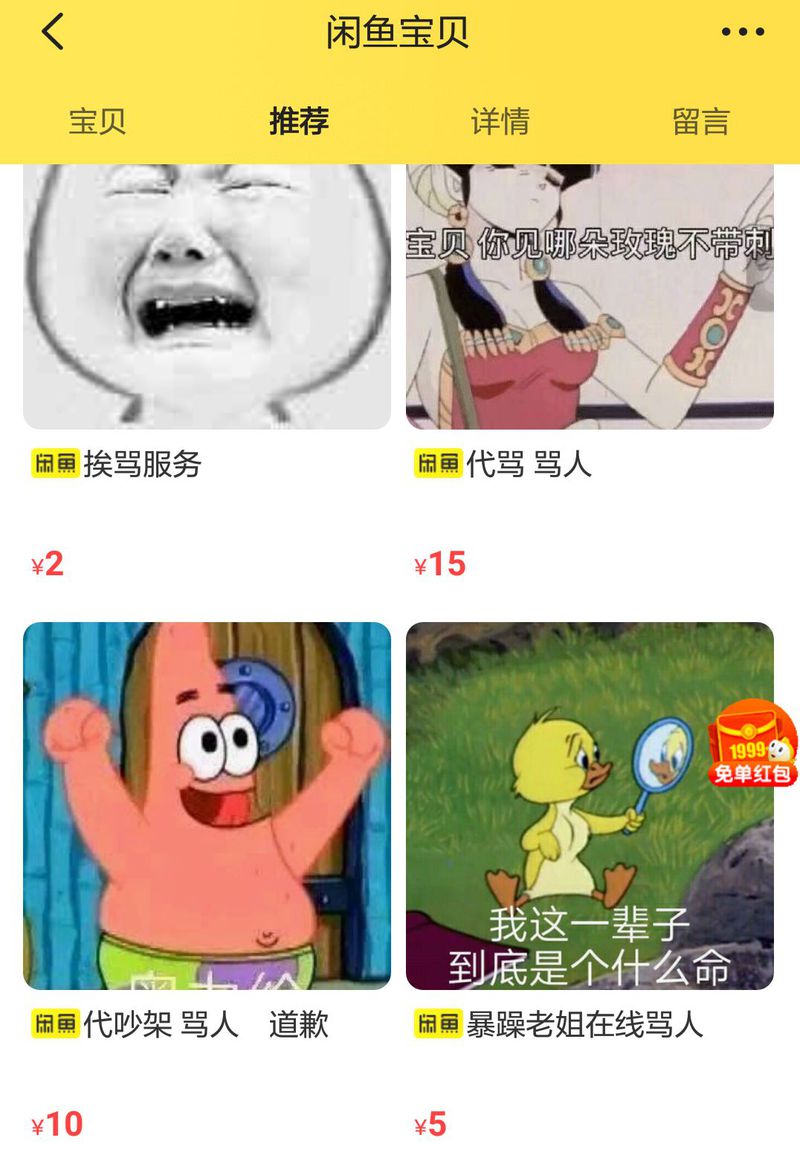

Though the poster probably meant it as a joke—refusing to fight with those in Chongqing, Sichuan and Guizhou, “because it’s impossible to win”—daima (代骂, “insult [someone] on [someone else’s] behalf”), or daichaojia (代吵架, “quarreling on [someone’s] behalf”), is a real service listed on Taobao for 5 to 200 RMB, according to the Chengdu Economic Daily.

Clients pay a third party to fling insults at anyone they hold a grudge against, be it an unfaithful lover or a business rival, by phone, SMS, or WeChat. There is the option to order lines from a script, add curse words, or quarrel in a regional dialect—and the client is kept “safe” by the use of virtual phone numbers that cannot be blocked or traced back to them.

The bottom-left ad offers quarreling, insulting, and apologizing—perhaps in that order?

Substitution services are not new: According to Automobile and Safety journal, designated drivers, hired to send intoxicated drivers home in their own vehicles, were in significant demand after drunk driving was criminalized in China in 2011, and their services have become available on mobile apps like eDaijia.

Daima has also existed at least since 2016, the year that that listings were removed from Taobao for “breaking moral codes.” They had reappeared on the e-commerce platform by 2017, and a few are still found on Xianyu, Alibaba’s second-hand trading platform, at the time of writing.

Professionals who eat and drink on a client’s behalf, or 代吃代喝, also debuted in late March: for a fee of 5 to 50 RMB, plus the cost of transportation and the product itself, clients can hire someone to consume any food or beverage that’s not hazardous or inedible, and send them photos and videos of the experience.

A “drink milk tea for you” service was viewed 16,418 times on Xianyu

To understand the counter-intuitive service—why spend money to not eat something?—China Youth Daily spoke with pro eaters who claim to provide clients with relief from long lines and weight gain. Many eaters are college students with high metabolism and lots of free time, hired to consume high-calorie items like fried chicken or the ever-popular “cheese-topped” milk tea.

Other service providers offer to pet a cat or dog (usually their own pet) on behalf of a client, or write compliments to the client in “praise groups” that went viral in March.

Hire someone to pet a cat for you at 1.99 RMB

According to one provider who spoke to the Beijing Youth Daily, these services are a symptom of today’s “sharing economy”: Instead of practical solutions like designated driving or buying goods from overseas (daigou), clients are paying to share in someone else’s enjoyment—the same reason audiences watch live-streamers doing mundane tasks like eating or putting on makeup.

There’s evidence, though, that the substitute “economy” is more hype than substance: On March 13, popular Weibo blogger @迷惑行为大赏 noted that two milk tea brands were hiring pro drinkers in order to promote their business.

One pro eater told China Consumer Journal that students like himself get into the business to earn extra money, “but there are only a few orders, mostly from curious customers.” Eating services on Xianyu only record a handful of sales, in spite of thousands of views.

Qi Xiaozhai, chairman of Shanghai Commerce and Economy Association, tells Xinhua that “social media-based consumption” can be attributed to the post-90s and post-00s generations’ “curiosity about new things,” and businesses employing new media for marketing and promotion.”

Ma Chuan, associate professor from the East China University of Political Science and Law, believes it’s premature to even label substitutes as a new “type” of consumption, telling Xinhua, “Novel, interesting, and interactive consumption attracts the young, but social media trends come and go quickly, barely forming a stable and sustainable consumption mode.”

Correction: This story was updated from its original published version on May 16.

Cover Image from Pexel