Despite laws and activism, China’s visually impaired often struggle for education and employment

Jenny Chen never imagined a day when she could no longer play her favorite video games. But after losing sight in both eyes in her early 30s, the Beijing native had to quit her dream job as an editor at a game company, and enroll in a school for the blind.

“After three decades of feeling like a normal person, I have to go back to a school and pick up new survival skills,” she laments to TWOC, adjusting the special glasses she wears with heavy orange lenses that enhance her vision. “I would rather have cancer than lose my sight.”

There are more than 17 million people across China with vision loss or impairment, according to a joint 2018 report by Tencent and the Information Accessibility Research Association, a Shenzhen NGO. Globally, the World Health Organization estimates that 1.3 billion suffer some form of visual impairment, and nearly 36 million are fully blind, defined as visual acuity worse than 3/60.

While public services have improved since the early 20th century, when chroniclers described the blind working as roadside performers, fortune-tellers, and beggars, China’s blind population continues to face educational, career, and even physical barriers, as well as discrimination and low recognition of their struggles.

Chen is now a vocational student at the Beijing School for the Blind, which also offers a modified mainstream academic curriculum for primary and secondary students. Students in the academic division learn additional skills like reading Braille and walking with canes, and can qualify for the National College Entrance Examination (gaokao).

The vocational division has two career tracks, blind massage and piano-tuning. The former is a state-sanctioned profession to alleviate unemployment issues among the visually impaired, and has its own professional association supported by the Ministry of Civil Affairs and the Ministry of Health. This curious partnership developed in the 1950s, when the government began offering professional training for disabled veterans, which included massage, weaving, and fortune-telling; only massage survived the economic privations and political purges in the decades that followed.

China now has around 20,000 licensed massage parlors, and many more roadside operations and unlicensed parlors—often based in illegally modified apartments in residential areas, and vulnerable to closure or demolition by the authorities. Not until 2017 did China’s Traditional Chinese Medicine Law give blind practitioners the same rights as sighted people to work as hospital masseurs.

Piano-tuning is the second most popular profession for the blind

Even so, the number of licensed clinics remains pitifully few compared to the size of the blind population—out of 52,700 visually impaired people living in Beijing, those employed as licensed masseurs is only in the double digits, according to 2018 CCTV report.

Private clinics can accommodate the rest, but offer few of the same guarantees in terms of working conditions and benefits for the masseurs—a prospect that worries Chen. “We are in such a weak position when negotiating on salaries and insurance,” she says. “I have a blind friend who used to be very talkative and happy, and when she started working, she gave massages all day long; she gradually became dull and withdrawn.”

Chinese media have reported other issues within the profession, from customers who take advantage of their masseur’s handicap to avoid paying, to operators who confine masseurs inside unsanitary rooms and parlors that are fronts for prostitution. A 2017 survey by Zhejiang University found that the average monthly income for blind masseurs was as low as 3,000 RMB.

Those already in the profession have tempered expectations. “Although I have zero social benefits or insurance, the salaries are about twice as much as I can earn in my hometown, and I’ve made many friends here,” says 37-year-old masseur Guo Ge, who has worked for seven years at Sheng Shou Blind Massage, a licensed parlor in Beijing’s Haidian district. Guo used to work as a chef in his native Shanxi province, where his wife and children still live; in his late 20s, he lost his sight and enrolled in a two-year massage course.

Blind school students often “buddy up” to help one another get around campus

At Sheng Shou, a dozen masseurs work from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m., providing stress relief at a rate of 88 RMB per hour for workers in nearby Zhongguancun, “China’s Silicon Valley,” as well as students from the competitive Peking, Tsinghua, and Renmin universities. In a typical day, Guo sees at least eight clients, mostly in the evening when the offices close for the day.

Although Sheng Shou offers meals and a dormitory for its workers, this communal style of living puts a strain on Guo’s other senses. After spending all day around clients and colleagues, “I just want to contemplate the future in a dark cave,” he says. “My wife is worried about me, but I always tell her I’m fine here. Only God knows how much I want to lie down in her arms, quiet as a child—I miss her so much.”

Although the government has vowed to improve standards and increase opportunities in the massage industry, many activists would rather see better prospects for the blind in mainstream education and employment. In a dark office at the Xin Mu Foundation, a Beijing-based NGO offering services to the blind, Dong Lina, a speech and language teacher, wears headphones to record standard Mandarin pronunciations into a microphone. Her lessons are distributed to blind students online all around the country with the aim of improving their competitiveness in the job market.

Dong, who lost her vision at age 10, trained as a masseuse after middle school, but began studying to pass the special gaokao for self-taught adult learners at age 27. In 2011 she became the first blind student to enroll at the Communications University of China. “Mainstream education is hard for blind kids, but if they can get through the difficulties, they can have more job opportunities in the future,” Dong, who is a licensed voice actor and broadcaster, tells TWOC.

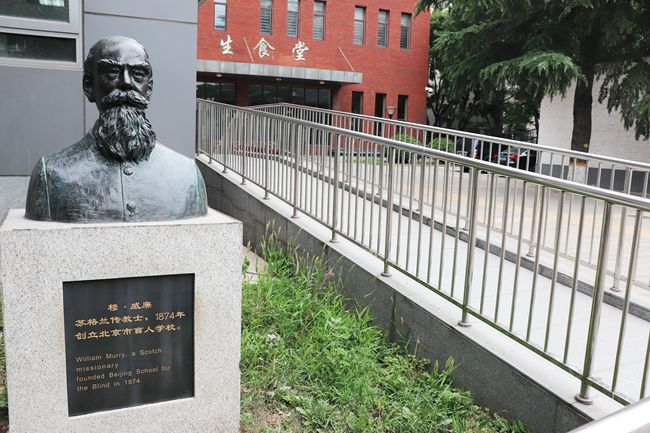

The Beijing School for the Blind was founded by missionary William Murray in 1874

However, according to a 2018 report by TechWeb, fewer than 200 visually impaired students in China are admitted to mainstream universities each year. Barriers to their education include a lack of Braille exams, though this had been made mandatory for every standardized qualification since the PRC’s Law on Protection of Disabled Persons in 2008.

Even those who pass the gaokao may still face arbitrary rejection—with universities claiming to lack dorms for the disabled, or Braille textbooks as in the 2015 case of Zheng Rongquan, the first blind student to pass the gaokao in Zhejiang province. Dong was denied her first attempt at taking an electronic gaokao in Beijing, simply because there was “no precedent” of blind students taking it.

These problems are compounded for those living in rural areas, which lack the educational infrastructure of cities. Families must either have a local residence permit (hukou) or pay social insurance in the city to enroll their children in the primary and secondary divisions at the Beijing School for the Blind; students in remote regions, such as Qinghai and Tibet, can apply for local funding to receive a better education in the capital.

Regional governments do arrange work for the blind under their jurisdiction, but these are still mostly in licensed massage parlors, government bureaus dealing with disability issues, and other offices that may not assign any meaningful work to their blind staff, according to Zeng Xin, a culture coordinator at Xin Mu. Private companies can also receive tax incentives for hiring blind employees, but few choose to participate.

Audiences listen to a movie at the Xin Mu Cinema

At Xin Mu, Zeng is in charge of running radio broadcasts, book donations, and “movie-narrating” programs, which all aim to enrich the education and lives of the visually impaired. “We share similar experiences of loneliness, disregard, and depression,” she says, pointing out that the blind don’t just require financial or material support from society. The NGO runs weekend English lessons, a Braille library, and the Xin Mu Cinema, where the visually impaired can gather every Saturday to listen to a film along with descriptions narrated by a volunteer. “Every time, the sightless spectators chat non-stop with each other, as if we’re family.”

But even in cities, the infrastructure still lags behind. “Tactile paving,” introduced by the Beijing government in 1991, is now compulsory in all cities; Beijing has more Braille pavements than any other city in the world. However, they’ve been labelled “death traps” by disability campaigners, frequently leading straight into trees, manholes, wiring, fences, and even off cliffs.

There is also a severe shortage of guide dogs for the blind; there were only six guide dogs in all of Henan province last year—and in Guangdong, just one. Chen Yan, a well-known Beijing piano-tuner, told the Legal Daily that it was “a matter of luck” whether she and her (now retired) guide dog, Jenny, would be allowed onto a public bus or taxi—and they are frequently ejected by subway staff ignorant of the difference between guide dogs and pets, or unfamiliar with laws supposed to guarantee guide dogs’ access to public property.

“Being afraid of street dangers, most blind people would rather stay at home,” Luo Zhilin, co-founder of Dialogue in the Dark, tells TWOC. This Shenzhen company, founded in 2015, has eight visually impaired employees out of a staff of 13, and runs counseling sessions and corporate workshops on accommodating the blind.

“We chose to have our office close to the subway station to help [our blind employees],” says Luo, who points out that many sighted people in China lack experience and empathy with the blind. In one of his company’s workshops, the client has to bring their employees into a dark room and solve a series of problems together, building team unity, while simulating the experience of blind workers. “Most people start to change their mind about blindness from here. Blindness doesn’t mean either a weakness or a superpower, but blind people do need mutual understanding.”

But the blind are still invisible to most of the Chinese public, shuffled into special professions and spaces, and only occasionally seen picking their way through the hectic thoroughfares of its cities. On Zhihu, a Quora-like Q&A app, the question “Why have blind people become more invisible these days?” attracted more than 200 answers. “They are in darkness not only physically, but socially,” goes the top response.

Out of Sight is a story from our issue, “Wild Rides.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.