A modern artist who transformed Chinese painting with his vivid portraits of history, horses, and wartime resistance

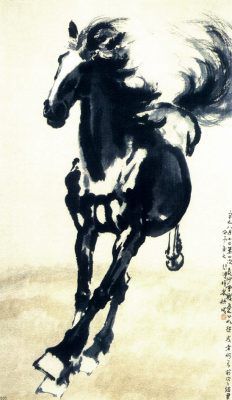

Horses have always been a common theme in Chinese ink painting, representing aspiration, ambition, and energy.

Under the brush of painter Xu Beihong (徐悲鸿), though, this noble animal became a symbol of national spirit and unity during a time of great division, the war-torn years of the 1930s and 1940s.

Xu is perhaps the most important name in modern Chinese art, but was born into an ordinary family in Jiangsu in 1895.

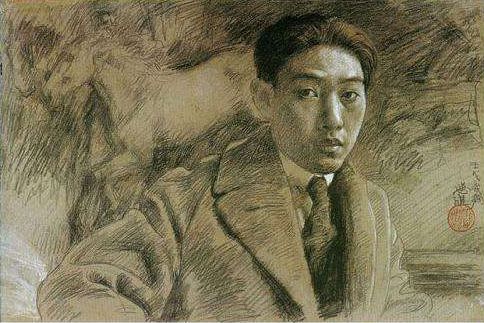

He learned traditional painting from his father at a young age. As a young man, Xu attended Shanghai’s Jesuit-run Aurora University and later became an instructor in Peking University, rubbing shoulders with writer Lu Xun, opera master Mei Lanfang, and other thinkers and artists of the time. But it was his study abroad at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, starting in 1919, and his subsequent eight years’ residence in Europe, that gave him a firm grasp of Western painting techniques and exposed Xu to the deep influence of French Realism.

“Self Portrait,” 1922

Xu returned to China in 1927. Soon after, the conflict with Japan escalated. It was during the anti-Japanese war that Xu produced some of his most famous works, portraits that charted the nation’s suffering as much as bolstering its national morale.

“Wounded Lion,” painted in 1938 after the fall of northeastern China to the Japanese invaders

“Galloping Horse,” (1941) a symbol of perseverance painted before the Second Changsha Battle against Japan’s armies

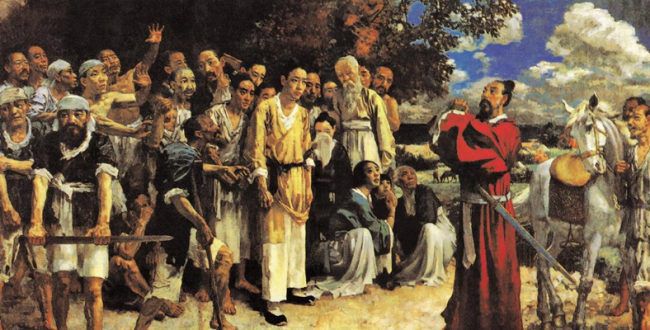

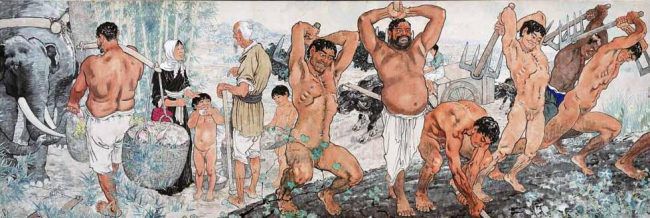

Besides ink paintings of horses, Xu also took inspiration from ancient history and created a series of epic color paintings in a similar patriotic spirit.

The 3.49-by-1.97-meter “Tian Heng and 500 Heroes” (1930) depicts Tian Heng, a nobleman of the Qi State, saying farewell to his followers after agreeing to submit to the conqueror Liu Bang in exchange for his followers’ lives. Xu had been disappointed at the ruling Kuomintang’s lack of effort in fighting the Japanese; his subject in this painting, taken from the Records of the Grand Historian, is meant to depict dignity in face of great danger.

“Tian Heng and 500 Heroes,” was painted in 1930 as a rebuke to the Kumonintang’s unheroic acts

The real history, in fact, had ended in tragedy: On his way to meet Liu, Tian instead decided to kill himself, and asked his servants to bring his severed head to Liu Bang to show his unbending will. On hearing the news, his 500 followers committed suicide as well.

In another painting, titled “The Old Fool Who Moved the Mountains,” Xu used traditional ink painting techniques to depict a classic fable from the Liezi, a fourth-century Daoist text, in which an old man vowed to remove the mountains blocking his way, tasking his descendants to devote themselves to that task. Painted in 1939, when World War Two and the Japanese invasion was in full force, the epic artwork expressed China’s national determination to drive the enemy out.

“The Old Fool Who Moved the Mountains,” painted in 1938, is one of Xu’s most epic works

While China was besieged with warlords and invaders, Xu held overseas exhibitions to raise awareness of the suffering going on in his motherland, and sold his work for charity. Among them, “Portrait of Miss Jenny” is regarded as a masterpiece. This oil painting, depicting an unsmiling Singaporean socialite, raised 40,000 Singaporean dollars for wartime relief. More recently, the portrait was sold for 50 million RMB at a Beijing auction in 2011.

“Portrait of Miss Jenny,” 1939

After the war, Xu was elected chairman of the Chinese Artists Association and appointed president of the China Academy of Art, continuing his artistic creation while educating the next generation of artists.

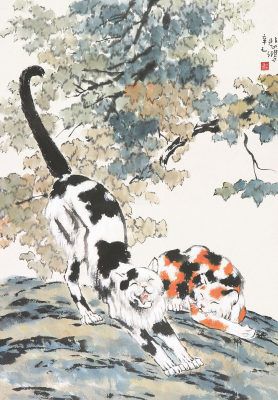

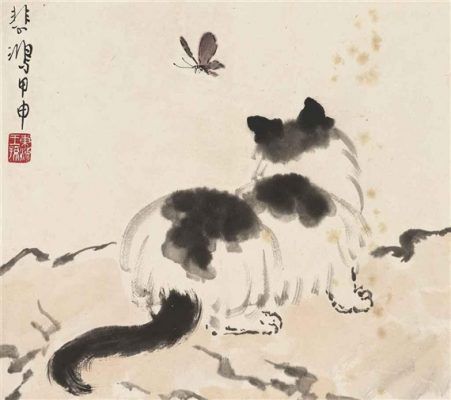

Although celebrated as a serious and emotive artists, Xu’s work embraced a variety of lighthearted subjects as well. He loved painting cats, once joking, “Everyone praises my horse paintings, but actually, my cats are better.”

“Two Cats,” 1941

“Kitten with Butterfly,” 1944

“Cats on Rock,” 1948

Xu died of a cerebral hemorrhage on September 26, 1953. Afterward, his widow Liao Jingwen donated 1,200 of his works an art collection to the state. Admirers can visit the Xu Beihong Memorial Hall—at 53 Xinjiekou North Street in Beijing—to remember the life of a great painter and admire his cutting-edge art.