The real story of Liangshan, the classic setting of “Outlaws of the Marsh”

These days, Liangshan Mountain (梁山) is considered a modest peak, not quite 200 meters above sea level, that casts its shadow on Dongping Lake. But there was a time when it was a formidable plateau of fortresses, surrounded by mountains and sprawling marshland, penetrable by only six narrow passes that together defended the headquarters of perhaps the most famous outlaws in Chinese history.

According to legend, they were the “108 Stars of Destiny,” the title given to the mortal reincarnations of demons who were banished from the immortal realm and imprisoned. Repenting their sins, they escaped, and were reborn as the 108 “righteous bandits” in Outlaws of the Marsh (《水浒传》), the earthiest and, arguably, most exciting of China’s canonical “Four Great Novels.” It is also known, depending on translations, as Water Margin, All Men Are Brothers, and Men of the Marshes; the outlaws’ adventures have spawned many hundreds of interpretations over the centuries, including a 1973 Japanese TV adaptation, several Shaw Brothers movies and TV series in the 1980s, video game franchise Suikoden, and numerous operas, plays, animations, and manga.

The original novel, written in vernacular rather than literary Chinese, is loosely based on the real-life exploits of Song Jiang (宋江) and his crew of 36 haohan (好汉, “good men”). Their stories share some historical similarity to the British folk fables of Robin Hood and his “merry men,” with both groups supposedly robbing from the rich to give to the poor, and undergoing considerable exaggeration in their stories’ retelling.

Song’s ragtag group of 36 rebels become the novel’s 108 semi-fictional outlaws, whose ranks include scholars, fishermen, martial artists, and soldiers. They are drawn to Liangshan Mountain because the area was notoriously remote, inaccessible, and lacking in even the most basic government administration. As in life, the main characters were blue-collar anti-heroes who fought the law (with the law only winning at the end by declaring amnesty and recruiting the gang as allies in a fight against foreign enemies).

Set during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), the book is both a gripping narrative and a powerful critique by a Han writer of the ethnically Mongolian Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368) and its corrupt imperial network. Thus, it was often consumed as a palatable form of literary rebellion against the much-resented Yuan. Later rulers, such as the Ming’s (1368 – 1633) Chongzhen Emperor, clearly saw themselves in the novel’s depictions of weak, greedy, and self-serving officials, and banned the book accordingly.

Today, Outlaws of the Marsh’s pointed literary critique no longer carries the same sting. The novel’s reputation perseveres, though, even if some of its subtext is less edgy and dangerous—a fate that mirrors its legendary location.

Liangshan Mountain, named after the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) Prince of Liang, whose tomb was located there. In the classic Chinese opera Black Whirlwind Presents Two Victories (《黑旋风双献功》), the mountain is described as having “72 deep rivers garrisoned with hundreds of warships. In 36 feasting towers, there is enough food for a million soldiers and their mounts.”

But this landmark is no longer a stronghold of roving revolutionaries, and the marshlands, if not gone completely, are vastly diminished. The tide of time turned against the region around the time the Yellow River shifted its course, draining the marshes. The banditry still continued for a few hundred years, but after the Qing (1616 – 1911) built a fort in what’s now Liangshan county, the area became no more or less dangerous than any other remote region.

A further shift of the Yellow River northward in 1853, far from rejuvenating the swamps, carried more sediment into the waterlogged regions. Human hands, in the form of dams and other drainage schemes, have since done the rest to pacify and dry out the area.

Of course, now that it’s safe to visit, the tourism industry is keen to play up the area’s association with violent outlaws and rebel compounds. Various sites in Shandong now purport to accurately replicate the literary locations depicted in Outlaws of the Marsh. Heze’s Water Margin City of Heroes (水浒好汉城) includes the Timely Rain Tea House (及时雨茶楼) and Aunt Sun Inn (孙二娘客栈), both serving dishes described in the novel. Dongping Lake Scenic and Historic Area (东平湖风景名胜区) has the newly built Liugong Mountain Fortified Village and Water Fortress (六工山水浒大寨), where the fictional bandits once trained for battle, as well as the ruins of a former mountain village said to have housed the original bandits. Juyi Island (聚义岛) is another spot worth seeing, with its Cangmei Temple (藏梅寺) built to commemorate the hero Chao Gai’s (晁盖) demise.

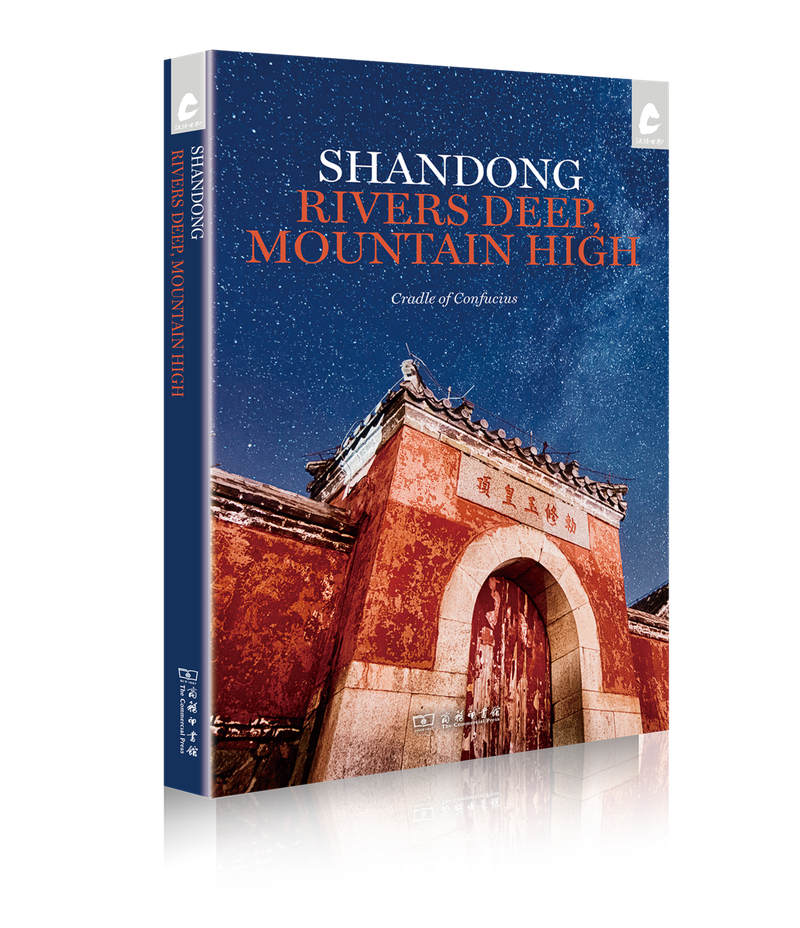

Cover image is of the Liangshan Scenic Area, Jining

Excerpt taken from Rivers Deep, Mountain High, TWOC’s newest guide to Shandong. Get your copy today from our online store.