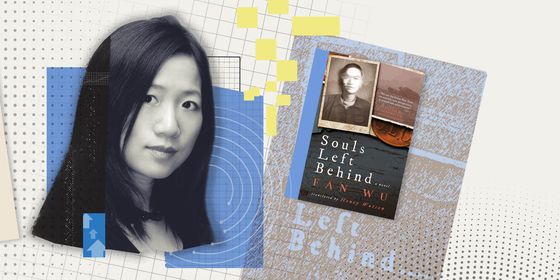

Sun Pin’s short story explores the foibles of romanticism in the modern day

To welcome Little Fish, Old Kang waited outside in the bitter cold for half an hour before he finally clocked her. Ensconced in her scarf and hat, she looked like an outsized rabbit bounding toward him. Little Fish waved two hands in his direction, shouting, “This place isn’t the easiest to find, y’know! I trekked all the way around in a big loop, and couldn’t find the road. Are all rich neighborhoods like this?”

Since Old Kang was setting himself up in a mansion for the first time, he was conscious of a slight shift in social status. He felt he had to act more dignified to fit with the atmosphere. Thus, he gave a broad smile, saying nothing further, and simply showed her in.

Little Fish’s surname, Yu, didn’t actually use the character for “fish.” She was a colleague of Old Kang’s before he had retired, a young lady of 30 who was old at heart. Outside of work, she liked to dabble in the odd line of verse, both crystalline and pristine. Each poem was signed off with her self-mocking pen-name: “The old-yet-young-lady, Little Fish.” Though she was three decades his junior, Old Kang could call her a close friend, because apart from a mutual passion for composing a verse or two, they shared the important experience of having been set up on blind dates. They had become something akin to each other’s reinforcements, with abundant real-world combat to show for it—enough to compile a guide book from. Especially so for Old Kang, who had lived long enough for his head of black hair to become a full shock of wispy white.

Entering the mansion, Little Fish peeled off her down jacket while stamping her feet and exclaiming, “Ahhh, so toasty-warm! Rich people’s homes always have perfect heating.” The house belonged to Old Kang’s younger sister, who had gone vacationing in Europe for six months. The house had been left unattended. Wisdom dictated that such a house was liable to fall to ruin, so she had taken the opportunity to invite Old Kang to live there—to water the plants, keep the place spick and span, act as a temporary security guard, and the like.

Old Kang and Little Fish had met one-on-one dozens of times before, yet this meeting was permeated by a brand-new feeling. Maybe it was the feeling of old friends suddenly being reunited on a snowy day, or the fission of two strangers meeting for the first time at a roadside wonton stand. It was a touch exciting, a touch wistful.

They drank two pots of tea and had a platter of snacks. Little Fish bit down on her biscuit and took a sip of tea in silence. There before Old Kang, she radiated that tenderness between them that belonged to comrades-in-arms, but also a little of a daughter who acts spoilt and naive in the presence of her father.

In the idleness after they’d eaten their fill, an even larger void opened up and hung over the room. It had nowhere to escape to. Old Kang suddenly seemed to have lost his nerve and took himself to another room, rooted about for something, and returned carrying an old photo album.

It held photos from when he was 5, 38, and 50. Little Fish flipped through the pages, when she abruptly pointed out a black-and-white shot of a young woman. She asked Old Kang: “What a beauty! Who is she?”

Old Kang gave the photo a glance and replied, half-modest and half-gleeful, “Real pretty eh? Everyone says so. Guess in those younger days it wouldn’t be wrong to say she was blessed with looks.”

At this he paused, averting his gaze, adding miserably. “She’s my ex-wife. We were married all of two years before separating. We were in our 20s at the time, now we’re both already in our 60s. Just like that, 30 years went by.”

“So back in the day you had a wife this beautiful? How come it ended in divorce?” Little Fish was shocked.

“We had a lovers’ quarrel back when we were young. I hid out at a friend’s place for a few days nursing my anger. I didn’t contact her. That was before most people even had phones, much less cell phones. She couldn’t reach me. Eventually I came back, only to discover her gone. I had no idea where she went, and couldn’t find her anywhere,” Old Kang recounted.

“Some more time elapsed, but we managed to meet up again at some point. But we felt estranged, and were arrogant in our youth. Neither of us was willing to back down first. By then there was no going back and we separated. Only after many years had gone by did it dawn on me—the significance of that turning point for us. I felt real regret then, but it was no use.”

“Did she ever remarry?” Little Fish asked.

“I heard she found herself a new man not long after the divorce, a factory worker or something who was really keen on her. The thing is, I also heard he only had one eye. One of his eyeballs was made of glass. He couldn’t turn it at all.”

“So did you encounter each other after that?”

“Oh I know where she lives, and I know which balcony is hers, but no…we’ve never crossed paths since...”

“Then why didn’t you ever remarry? You just haven’t found the right woman in all those 30 years?”

Old Kang let out a ponderous sigh, “It’s not that there hasn’t been a suitable match. There was a middle school teacher, a real stand-up woman. She was very good to me. We nearly registered at the marriage office. But when things came down to it, I couldn’t bring myself to…because I couldn’t let go of my former wife. I still thought the world of her. No other woman could hold a candle to her in my eyes. Don’t you know? Although she has married someone else, all this time I’ve harbored feelings and I’ve been waiting for her to come back.”

“No wonder you’ve never had any success from blind dates in 30 years! You’re not really there to date, you’re just passing the time, fooling yourself,” Little Fish accused him.

All of a sudden, tears welled up in Old Kang’s eyes, “Damn right. I knew 30 years ago that I would be spending my remaining years alone. But you know what? The reality is I’m not scared. Not in the slightest. What a glorious thing to pass the remainder of my life waiting for somebody to return. Whether or not she comes back, what’s the difference?”

He continued: “Do you know, at dusk each day for over 30 years now, I’ll take a walk over to Peach Garden Alley? Three hundred and sixty-five days a year. Regardless of the season, rain or shine. I’ve never missed a day. And do you know why? Because she lives on Peach Garden Alley. I can name the building, the unit number—down to the very window. Her balcony overlooks the street from the sixth floor. It’s crowded with small trees and flowers. From underneath I can catch sight of a pot of blood-red geraniums. I’m certain she planted them, because she’s into flowers. Geraniums are her favorite flower—just like when she was young.”

“Then why not go and seek her out?”

“No. She’s already got a family of her own. Besides, word is that her new husband treats her well. Plus, I don’t want her to know anything about my circumstances. That I haven’t remarried in all this time. Nor that by the age of 50, my hair had all but gone white. I only want to pass by under her balcony each day, to see her shadow at a distance and know she is still living there. Still cooking, planting flowers, listening to music…To know she is getting along fine.”

He continued, “As I come upon her balcony each day, I only have to stand and raise my head awhile. To gaze above at that pot of geraniums and see how it is growing. To see whether or not there is a light in the room behind. Whether or not she is currently out there watering the plants. Some of which are in bloom, others which have wilted. Some are growing larger and larger, with branches that have not been trimmed back—they peek out from the cracks in the railing. When the flowers die, they get replaced with new flowers, but somehow that pot of geraniums is always there. And every time I stand under that building I’m able to see that fiery burst of color.

“Thirty years have gone by like this. And without fail, as I cross under her building, I can see a light in the window. Sometimes I catch faint voices floating out or the sound of music. Plants on the balcony cast shadows across the window, always framing a woman’s silhouette as she waters or attends to the plants. It looks like a paper-cut pasted on the surface of a lantern. Even if I can’t make out her face, I’m satisfied to see her shadow. Though 50 years have passed without my having seen her, I can still recognize her shadow from a distance. So I watch surreptitiously and leave after a while.”

“Has she clued into the fact you pass by each evening?” Little Fish demanded.

“Beats me. Honestly, I don’t want her knowing that I take that route every day. It’s about knowing she is still around. To me, although we’re long divorced and I can’t see her features directly, I am still nervous as hell she isn’t getting on well. When I walk that way, I’m sure to listen out for the sounds of an argument up there on the balcony. For the sound of a woman crying. There isn’t, there has never been. And so I am even more gratified.”

“Well perhaps it’s the case that in all this time she hasn’t noticed you passing under her balcony. That she pays practically no attention to the pedestrians halting beneath her. That she is busy living her own life, in her world, without anything left to do with you!”

“Doesn’t matter. It’s my own concern. Either she knows or she doesn’t, it’s no skin off my back.”

“But you aren’t exactly getting any younger, aren’t you afraid of becoming increasingly isolated? If the day comes you are incapacitated and can’t get out of bed, with nobody at your side to offer you care, doesn’t that scare you?” Little Fish persisted.

“I think it’s lonelier to have nobody in your heart to miss. What do you think people live their lives for? Have you thought about this? I have spent these 30 years thinking about it.”

“So back when she first married someone else, did she consider how you felt?”

“Let me tell you. Every time I peer into the mirror, I look at my own eyes. Then I’ll imagine one of them is a glass eye, then I try to turn it but it won’t turn. I imagine having to live like this all the time, and my heart is pained to the extreme. If we hadn’t divorced in the first place she needn’t endure this bitterness. She remarried as a means of punishing herself. Not to punish me. It’s something I understand all too well, only I’m using a different method.”

“How can you be sure she’s been living there the whole time?”

“Year after year, that pot of geraniums has been flowering out on the balcony. I think as long as those geraniums continue to bloom, that’s her way of telling me she is still around.”

“Truthfully, you’re dying to let her in on it, to see you here in this big mansion to show her how well you’re doing for yourself. Probably up to entertaining the idea of receiving her here, if only to sit a while, to drink a cup then leave,” declared Little Fish. “This is what you feel she deserves, right?”

“What of it? It’s not something I will ever do.”

Little Fish shrugged out an extended sigh, breaking in with, “So that’s how it is? How about you delay that little walk of yours today and I come along with you, see what happens?”

Once the sky had darkened to black, Old Kang and Little Fish emerged on Peach Garden Alley, looking like co-conspirators concealing a secret. Both of them were fairly nervous. Without a word, they both headed for the building, looking up at the sixth floor as they walked. In the distance, lamplight spilled over the balcony. Sure enough, the shadows of plants were being projected onto the window, but there was no human silhouette.

The pair made their slow approach. Just as they were reaching the spot beneath the building, their eyes registered a figure emerging from under a big peach tree opposite them. It was a woman. Little Fish noticed Old Kang’s entire body trembling. Unable to move, he stood staring at the woman under the tree, as if he had been frozen on the spot. Little Fish wondered if it was possible this was the ex-wife Old Kang had spoken about. It certainly seemed like she had been out here waiting for Old Kang to arrive.

As these thoughts came to Little Fish in jumbled bits and pieces, the woman met their eyes. She appeared similarly surprised, appeared to hesitate for a moment, then changed course and walked right over, sparing but a single glance at them. She didn’t say anything at all, but walked past them to enter the pitch-black building, disappearing inside. Soon after, the light in the sixth-floor window suddenly blinked out.

Old Kang was still frozen to the spot. Little Fish’s confusion was evident, “That was her…That’s your ex-wife isn’t it? Can’t you see she was standing here waiting for you. What does that tell us? It means she is well aware of your daily walks underneath her balcony. That she is used to seeing you at a fixed time. But today you were running later than usual. She became nervous when you didn’t show. So she came down to wait for you. And because of this, you two were able to run into each other.”

Just then Old Kang finally seemed to recover his breath, raising his head to that darkened window, then hanging it low. “It’s not her.”

“It’s not her?”

“Not her.”

When twilight fell the next day, Old Kang and Little Fish found themselves emerging again on Peach Garden Alley. Standing beneath the balcony, Old Kang felt a surge of hesitation. He felt unable to bring himself to enter.

“Did we not go over this yesterday?” Little Fish nudged.

And without another word, she dragged Old Kang into the building, rushing him all the way up to the sixth floor. Panting, she knocked impatiently. Old Kang’s face had lost all its color. The hand he put out to wipe away his sweat was trembling nonstop. He had all but retreated behind Little Fish. A beat of silence greeted the knocking, but after a moment, a voice sounded inside. The door opened a crack and there stood the same woman they had seen the night before.

Walking inside, Little Fish thought this woman looked as though she lived alone in this (not large) home. No other silhouettes presented themselves. The place had been kept in good order. Yet there was this desolate and oppressive melancholy to it, as if it was a long time since this place had known human habitation. Little Fish looked out onto the balcony. It was planted chock-full with flowers. The most eye-catching of all was that pot of geraniums, visible from below. It had been specially placed on a tall stand, its flame-red assemblage at the height of its bloom. It stood out among the other flowers, and someone needed only raise their head from below to see them.

Old Kang’s lips parted, then closed, then parted again. He simply couldn’t muster a single syllable.

As Little Fish began to get impatient, the woman suddenly opened her mouth to address Old Kang, “You’ve come looking for Zhang Hong, right? I’m afraid Zhang Hong passed away 12 years ago from a terminal illness.”

“What?” Old Kang and Little Fish were both dumbfounded.

The woman swung around and headed for the balcony. She lifted the pot of geraniums, cradling it carefully, and re-entered the room. She placed the pot down in front of them, explaining, “Zhang Hong cottoned on pretty early that you were walking by in the evenings. She planted that pot of geraniums for your sake. Putting out the signal she was getting along fine, so you wouldn’t go worrying yourself. Actually, you weren’t aware, but she had been hiding across from you under that big peach tree watching you each time you stopped by to gaze up at the balcony. The whole time, she was counting on you to make your way up to her. Year after year she persisted, secretly watching your back from behind that peach tree as you gazed up at these geraniums.

“After she fell ill, her husband hired a nanny to come take care of her,” the woman continued. “That was me. She was bedridden for two years, but she urged me over and over to stand on the balcony and water the plants at the appointed time at dusk. We had a similar height and she thought our figures resembled each other’s, so from far off it would look just as though she was standing there. When she knew she was about to die, she urged me time and again to stick around and care for her husband, while making it crystal clear I was to be out there on that balcony at the usual time, for your sake. To have you think she was still with us, that she was still doing fine.”

Old Kang crouched down, leaning over the pot of geraniums. He closed his eyes, and quietly pressed his headful of white hair into the blood-red petals.

The woman continued, “Last night, I was standing out on the balcony and when you didn’t show, I didn’t know what to think, so I decided to wait downstairs. That’s how we managed to cross paths. I never had any idea what to say to you. I married Zhang Hong’s husband after she died, and he passed away himself just half a year ago. Before dying, he said I could remarry, but please continue living here so I can keep up my nightly balcony appointment. He also knew about your excursions every evening.

“I thought to myself—I’ve been married twice; divorced once, widowed once. I’m getting up there in years. What is it to me now whether I remarry? My only remaining wish is to return to my hometown. It’s just that I knew you would be making your rounds every day, and I had no clue how I ought to bring it up with you. Now, since you’ve finally come, I can just tell you: If you’re so inclined, that geranium is yours to take back with you. If you’d rather not, you can leave it here, and I’ll bring it back to my hometown with me.”

Old Kang left Peach Garden Alley clutching the pot of geraniums, Little Fish trailing behind. As they parted, the night sky began to fill with snowflakes. Before long, their bodies were dusted with white. Old Kang hid the geranium under his coat and walked slowly, as if he were carrying a newborn child.

From that day on, Old Kang never returned to Peach Tree Alley. Even if evening fell and he was out on a walk, he would deliberately choose a different route that would avoid passing by that alley. By contrast, as spring rolled around, Little Fish found herself strolling Peach Garden Alley, now buried 10 centimeters thick in peach blossoms. A light breeze whisked by, sending the blossoms aflutter like snow to carpet the pavement.

Little Fish stood a long while by those two large peach trees and looked at the pedestrians as they went by, just like all those years Zhang Hong had stood here watching Old Kang surreptitiously from behind, day after day. She lifted her head, narrowing her eyes to seek out the sixth-floor balcony. Under the rays of spring, it was the same balcony, but it was already deserted and possessed of a strange desolation. She didn’t know where the flowers had gone. The window, which had seen better days, was shut tight. There was no trace of lights on the inside. It had the look of a place that hadn’t been lived in for a while.

Sometime in the last few days, Little Fish had heard a colleague from the office mentioning how Old Kang had never married, and couldn’t possibly have had an ex-wife.

Now, Little Fish stood there under the gradually darkening sky, raising her head to gaze up at the mysterious balcony, thinking to herself, “It’s not important.”

No, it was no longer important.

Balcony | Fiction is a story from our issue, “Access Wanted.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.