China’s netizens come up with creative ways to bemoan mandated workdays around holidays

The tourism sector in China finally roared back to life during the Labor Day holiday after three years of suppressed visitor numbers. With Covid-19 travel restrictions removed, visitors clogged up roads, highways, and tourist spots in a bout of what has been dubbed “revenge travel (报复性旅游 bàofùxìng lǚyóu)” to compensate for previous missed holiday opportunities.

With 274 million domestic trips over just five days during the Labor Day holiday (up over 70 percent compared with 2022), and travel spending of over 148 billion yuan (higher than the pre-pandemic spend during Labor Day 2019), netizens have labeled this year’s May break “the hottest Labor Day holiday in history (史上最火五一 shǐ shang zuì huǒ Wǔ Yī).” But though tourists have been enjoying the freedom to travel, many have also taken aim (once again) at what is perhaps one of China’s most hotly debated policies: ”make-up workdays,” or 调休 (tiáoxiū).

While the official calendar shows Chinese workers enjoy 26 days of public holidays in 2023, a closer look also reveals several 调休 days—mandated workdays on weekends that offset some of the days off.

Taking the recent Labor Day holiday as an example, it appears that workers get five days off (from April 29 to May 3), but two of those days were already on the weekend, while there were also two additional workdays on Sunday April 23 and Saturday May 6. That means cumulatively workers only got one additional day off.

This “artificial long holiday (人造长假 rénzào chángjià)” enrages netizens, with many suggesting it shouldn’t be called a “holiday (放假 fàngjià)” but a “holiday loan (放贷 fàngdài).”

The number of days one actually gets off work is sometimes difficult to calculate. As one netizen put it recently: “We need to look it over multiple times just to understand it. It’s as complex as the rules for discounts during the Single’s Day shopping festival (得看好几遍才能看懂,复杂程度堪比双十一满减规则 Děi kàn hǎo jǐ biàn cái néng kàndǒng, fùzá chéngdù kānbǐ shuāng shíyī mǎnjiǎn guīzé).”

Longer holidays like Lunar New Year and National Day in the first week of October are lauded as “Golden Week (黄金周 huángjīnzhōu)” and “Happy Seven Days (七天乐 qītiān lè),” but when you subtract weekends and two days of 调休 as part of these holidays, workers only get three days rest that they don’t have to make up. “How can it be called a holiday? It’s more like a fake break (这哪是放假啊,这是假放啊 Zhè nǎshì fàngjià a, zhèshì jiǎ fàng a),” wrote one disgruntled Weibo user recently, playing with the order of the characters in 放假 (holiday) to turn it into 假放 (fake break).

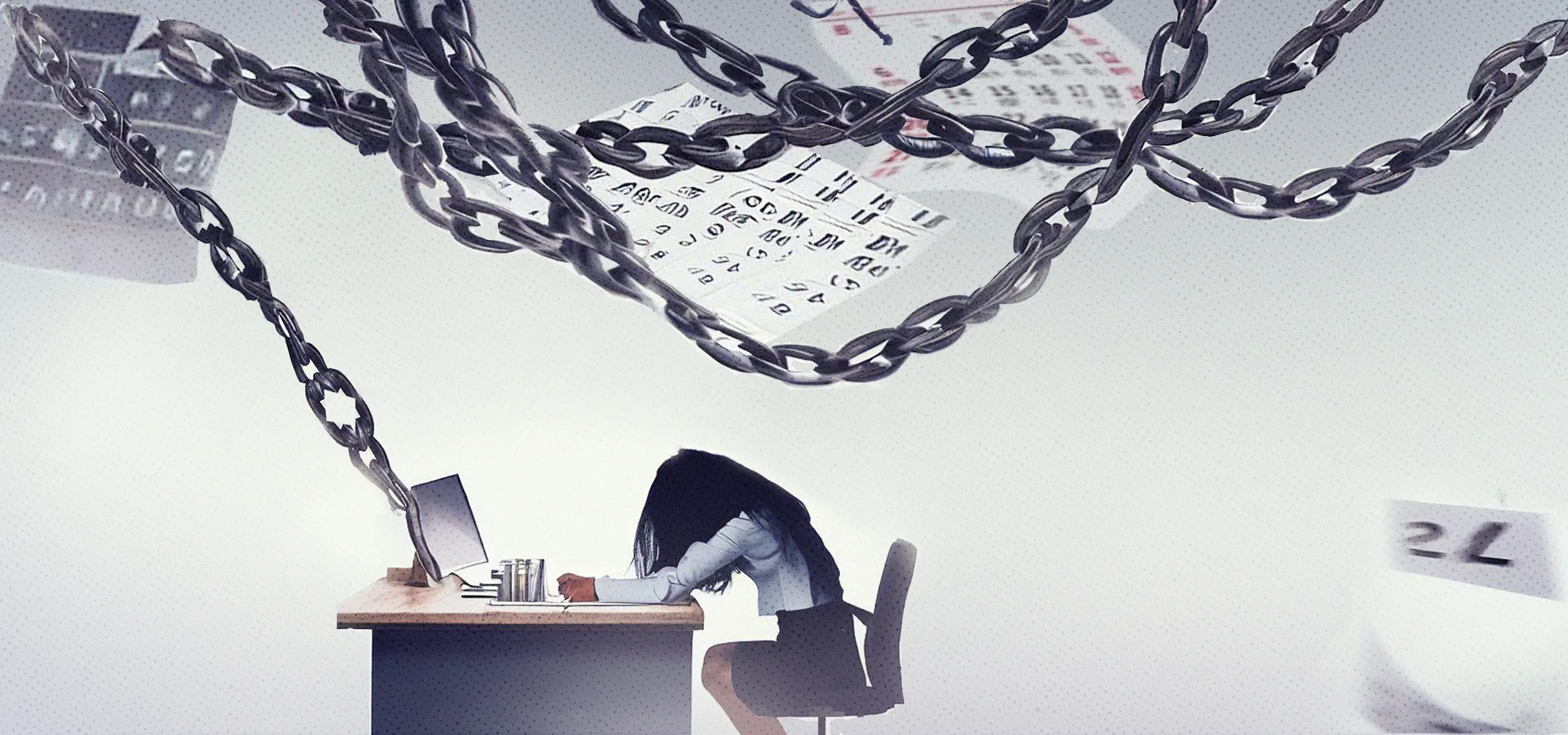

Forced to work from Sunday to Friday, many stressed workers struggled to comprehend the six-day week before the Labor Day holiday: “Today is supposed to be Sunday, but it feels like Monday. And even though after today the Monday feeling should be gone, tomorrow is still going to be a Monday (今天明明是礼拜天,却仿佛过出了礼拜一的感觉。虽然今天过出了礼拜一的感觉,可明天还依然是礼拜一 Jīntiān míngmíng shì lǐbàitiān, què fǎngfú guòchūle lǐbàiyī de gǎnjué. Suīrán jīntiān guòchūle lǐbàiyī de gǎnjué, kě míngtiān hái yīrán shì lǐbàiyī).”

With so few days off to enjoy, many packed in busy holiday schedules. Combined with the six-day work week prior to the break, many now find themselves exhausted, facing an imminent one-day weekend, and suffering from “post-holiday syndrome (节后综合征 jiéhòu zōnghézhēng)” with symptoms such as feeling drained, tired, and lacking motivation. “For one Labor Day holiday, I suffered for four weeks (为了一个五一,整得前后四个星期都难受 Wèile yì gè Wǔ Yī, zhěngde qiánhòu sì gè xīngqī dōu nánshòu),” goes a popular complaint online.

They have described the hated adjusted workdays as the equivalent of: “Making you stay awake for two days and then sleep for 25 hours (让你连续两天不睡觉,然后睡25小时 Ràng nǐ liánxù liǎng tiān bú shuìjiào, ránhòu shuì èrshí wǔ xiǎoshí)” or “not eating today and tomorrow, and then eating nine meals the day after tomorrow (今明两天都不要进餐,后天吃九顿 Jīn míng liǎng tiān dōu búyào jìncān, hòutiān chī jiǔ dùn).”

“We are not machines that can be prompted by simple calculations. Today’s meals must be eaten today. Today’s sleep must be slept today. And this week’s weekend must be enjoyed this week (人不是机器,不是简单的计算可控制的。今天的饭必须今天吃,今天的觉必须今天睡,本周的双休必须本周休 Rén bú shì jīqì, bú shì jiǎndān de jìsuàn kě kòngzhì de. Jīntiān de fàn bìxū jīntiān chī, jīntiān de jiào bìxū jīntiān shuì, běn zhōu de shuāngxiū bìxū běn zhōu xiū),” one cried.

Many can’t help but feel these extra workdays are just another way they are exploited like “leeks (韭菜 jiǔcài).” This popular metaphor refers to how leeks grow back quickly after being cut, only to be harvested again, in an endless cycle of growth and disappointment. One popular comment suggested they hadn’t recuperated nearly enough: “The time saved through make-up days is not even enough for leeks to grow (调来调去匀出来的那点儿时间,韭菜都缓不过秧来 Tiāolái tiāoqù yún chūlái de nàdiǎnr shíjiān, jiǔcài dōu huǎn bú guò yāng lái).”

With Saturday this week another workday, workers are still waiting for the make-up workdays of the Labor Day holiday to end. Some fear they might not make it to then: ”What day of the week does your company have off? We get a holiday when we’re dead! (你们单位都是周几休啊?我们是至死方休啊!Nǐmen dānwèi dōu shì zhōujǐ xiū a? Wǒmen shì zhìsǐ fāngxiū a!)”

Even if they do manage to soldier on, Dragon Boat Festival is coming in June, and that means another make-up workday on a Sunday. Better get prepared.