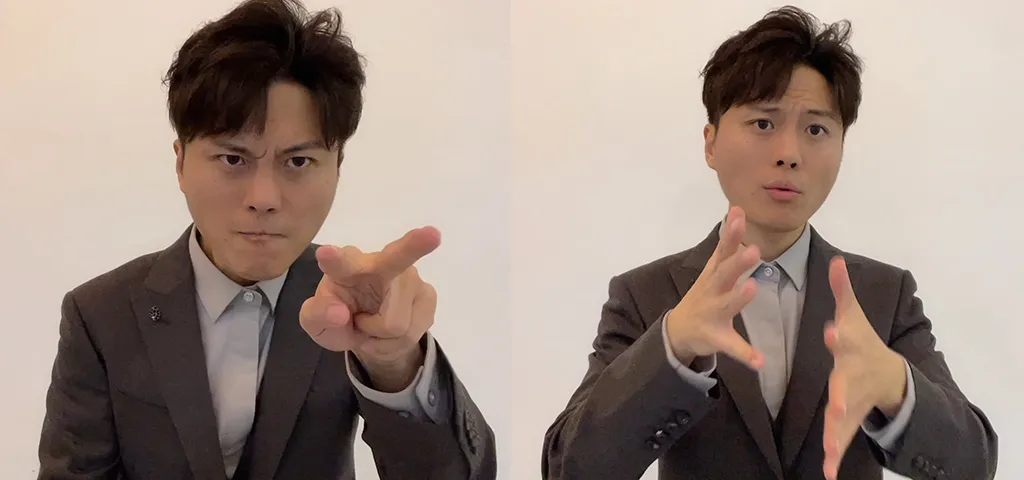

From driving classes to police detention, a young interpreter has spent over 20 years advocating for improved sign language and better services for the Deaf in China

1

A Native Sign Language Speaker

Hi everyone, Xiao Chi here. I live in Dalian, where I work as a Chinese sign language (CSL) interpreter.

My family is no ordinary family. CSL—otherwise abbreviated as ZGS—is actually my first language, though I did grow up in a bilingual environment with spoken Chinese as well. Up until my late teens, I spent every other month living with my parents, and the months in between with my maternal grandmother. My grandmother‘s was a hearing household; only my mother is deaf in their family. However, on my dad’s side of the family, my father, uncle, aunt, and great-uncle were all deaf. Their friends, who often came over for a meal or to take me out on a playdate, were deaf too.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always been aware that my parents were different from others. Here, a memory comes to mind. I must have been 7 or 8 years old, and I still slept in the same bed with my parents. One night, I suddenly woke up to this really strange impression that there was something moving in our bedroom. It was my folks, chatting under the moonlight; already at that age, I knew that sign language relies greatly on a light source. Filled with curiosity, I took careful mental note of their every movement. It dawned on me that my parents kept track of each other’s speech by touching each other’s hands and faces. It was rather romantic.

Story FM: Facial expressions and body language are just as important to sign language, serving a role similar to modal particles and adverbs in our regular speech. That’s why Xiao Chi’s parents were touching each other’s hands and faces in the dark.

Take the words “don’t know.” In CSL, you sign those by “taking your palm to your forehead, swiping to the other side, and keeping a puzzled face all throughout the sequence.” Whenever you’re describing a certain motion, your body posture reflects the degree of movement. Body posture is also crucial for you to tell different characters and their roles apart in sign language storytelling.

Xiao Chi discovered early enough that the exaggerated movements and expressions typical of sign language often attract everyone’s attention. As a child to deaf parents, mastering CSL was essential for him.

Xiao Chi: I started working as a CSL interpreter when I was about 4 or 5 years old at the family’s paint factory that employed all of my relatives—my grandfather, my aunts and uncles, and my parents, too.

Growing up, in the absence of my grandpa or a hearing employee around to answer calls from customers, I was in charge of the phone. My deaf relatives only knew there was an incoming call if they saw the phone light up.

I’d say, “Hello, this is Jianhua Paint Factory” and relay whatever order—say, a number of buckets of paint—to my mom. She’d approve and I’d say “Yes” to the customer. I’d also ask stuff like, “How many buckets for the indoor walls and how many for the outdoor walls?” And so we trudged along. Colors such as ocher were actually the most challenging to interpret, because sign language will only describe a few basic hues, but a paint factory deals with a large color catalog. My mother held up a chart for me to identify each color. If the customer wanted two barrels of pink, I’d point it out to Mom on the catalog.