As the garment industry of Guangzhou’s Kanglu area winds down to its last days, TWOC captures life in for the 100,000 workers and factory bosses in its urban villages

A massive truck skillfully winds its way through the narrow pathways of the urban village. A mechanical arm reaches high from the truck, scooping away piles of construction waste from the rooftop of a three-story residential building, where workers have been slowly taking apart the blue steel plates that once marked the boundaries of a makeshift clothing factory.

In the past five months, over 100,000 residents of Kanglu district, who hail largely from central China’s Hubei province, have listened to the resounding rumble like a countdown of their days in the village.

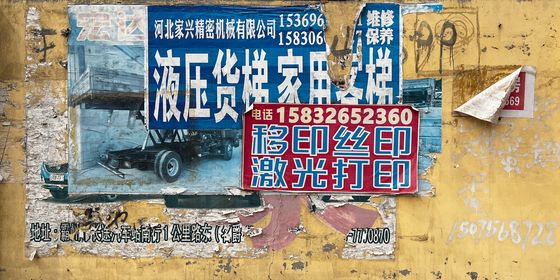

Kanglu is a local nickname for the area consisting of Kangle and Lujiang, two former villages that have been swallowed up by the urban sprawl in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou. It is a renowned hub of garment production in the Pearl River Delta region. Within 10-minute drive, the Zhongda Textile Market serves as a vital lifeline to the numerous small and large garment factories nestled within Kanglu, ensuring a steady supply of textiles. The garment factories operated around the clock, ceaselessly churning out orders for buyers around the world.

Though data on Kanglu is sparse, the garment production of Guangzhou reached 720 million pieces in 2013 alone, after a decade of rapid increase that only began to slow down in 2014.

However, the living conditions within the “handshake buildings” of the Kanglu area—built so close together that residents could exchange high-fives out of their windows—have long worried the authorities. This thriving community might be seeing its last days, as the local government cracks down on illegal construction and fire hazards resulting from landlords who’ve added stories to their rooftops, which they could then rent out to garment factories and workshops.

In October 2022, a devastating Covid-19 outbreak erupted within Kanglu. The densely populated district, coupled with inadequate sanitation measures, hastened the spread of the virus. Consequently, local authorities enforced a prolonged lockdown in the Kanglu area, lasting for over 40 arduous days. This dealt a severe blow to the entire garment village, causing suppliers to miss out on the peak fall-to-winter production season in October and November.

On February 10 this year, a conference held by the district government took place in Lujiang village to address the demolition of illegal structures in the Kanglu area. “At least this time, they had the courtesy to warn us ahead of time,” a 56-year-old migrant factory worker surnamed Wang tells TWOC. “When we used to live in the urban villages of Shenzhen, [the officials] would often come one night to tell us to move out the next day.”

The Guangzhou municipal government indeed offers an alternative to the workers like Wang, as it aims to consolidate the small factories for an “industrial upgrade.” Workers and factory owners have been offered incentives (such as a moving allowance of up to 100,000 yuan, rent reduction, and free scooters) to move to a newly built industry park situated 80 kilometers away in Qingyuan, a city only about half an hour from Guangzhou by high-speed rail.

However, for many factory workers, only the Kanglu area offers the high wages and flexible work schedules that satisfy their needs. “[The atmosphere] is quite free here. If there is a profitable deal I will work, but if not I just hang out and have fun,” Ouyang, a garment worker in his 50s, tells TWOC from his seat on a set of stairs by the street. Every morning, Ouyang rides his scooter to Kanglu from another village, as he can earn a higher salary here. According to Wang, workers can typically earn between 400 and 700 yuan per day depending on their skills and efficiency—relatively generous for laborers with little education.