Almost unheard of 20 years ago, eating disorders are silently maiming a generation of young Chinese

“I knew very well that I was not having a stomach problem, nor had I been in a bad mood, nor had I been too tired to study,” wrote Xuanxuan, a Shanghai ninth-grader, in an eating disorders support group on Baidu Forums last summer. “I became abnormal due to other reasons—my unspeakable secret.”

Since she was 9 years old, Xuanxuan would lock herself in her room every night after dinner. She would weigh herself, and then lie on the floor in tears. Like an estimated millions of Chinese, mostly young women, Xuanxuan struggled with anorexia nervosa, a psycho-physiological disorder that manifests in self-starvation in pursuit of a distorted body ideal.

Anorexia nervosa is the deadliest mental disorder in the world, according to the US National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Around 18 to 20 percent of those who suffer from it die within 20 years due to organ failure or suicide.

Along with other eating disorders like bulimia nervosa—characterized by cycles of binging and purging—and binge eating disorder, anorexia emerges from a confluence of genetic, psychological and environmental factors. Typically peaking in the teenage years, eating disorders disproportionately affect females to males at a ratio of 9 to 1, and often arise in families with acrimonious or distant parent-child relationships.

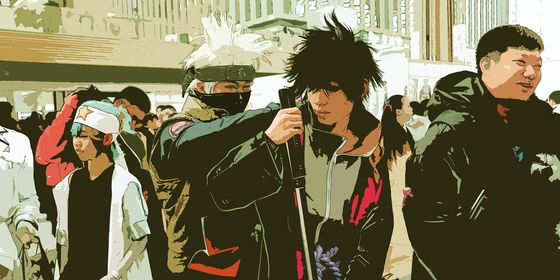

Despite its lethality, the disorder remains largely misdiagnosed and misunderstood in China, where mental disorders, especially eating disorders, are still a novel concept.

A public installation challenges mall-goers to prove their “perfect body shape” by fitting through thin slats

“For parents who grew up in decades characterized by poverty, starvation, and the Cultural Revolution, food and eating are so precious. Many can’t understand how, in this era of economic prosperity, their children refuse to eat,” says Joyce L. C. Ma, professor of social work at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and consulting family therapist at the Shenzhen Nanshan Hospital.

“There’s no doubt they love their children. But some fathers who come to me beat their children for choosing to starve themselves,” says Ma, who has counseled families regarding eating disorders for 20 years. “I tell them, your child has an illness, you can’t beat your child, you have to help your child.”

While eating disorders were virtually unreported in Asia just decades ago, they have risen in the region at an alarming rate. Psychologists began recording instances in Japan in the 1970s, and then in Singapore and South Korea. The first reports of bulimia cropped up in Hong Kong in the 1990s.

There is evidence that eating disorders follow economic development. A 2000 study comparing female high school students in three cities found that rates of disordered eating and body dissatisfaction were highest in Hong Kong, followed by the coastal first-tier city of Shenzhen. It was lowest in the capital of Hunan province, Changsha, in central China.

As China’s middle class ballooned, so has the prevalence of eating disorders. A 2013 study found that the rate of eating disorders among young female university students in the city of Wuhan were on par with those in developed countries. In a 2015 paper, Kathleen Pike, executive director of the Global Mental Health Program at Columbia University, blamed the rapid pace of societal change and rural-to-urban migration for creating “economic stress, competition, and the disruption of social and emotional support” for Chinese families, leaving them vulnerable to psychological disorders.

Xuanxuan, like many children growing up in the 2000s, was left in the care of her grandparents as her parents sought work in the city. A precocious child, she pursued perfection in every area of her life, from scoring at the top of her class in academic tests to weighing the least in physical exams at school.

Public schools weigh students as part of physical exams, but don’t tend to provide lessons on healthy body image

When another girl in Xuanxuan’s class announced that she weighed 0.3 kilograms less than her, and taunted her, Xuanxuan was incensed. At home, she dumped her favorite dishes in the swill barrel when her family wasn’t looking, and substituted her meals with a 30 gram portion of bean paste and a bowl of soymilk.

Concerned with her dwindling food intake, Xuanxuan’s mother brought her to a local clinic, where a doctor diagnosed her with a weak stomach and prescribed traditional Chinese medicine. It was only after her mother found a video about anorexia online that her family became aware of the severity of her condition, taking her to a Shanghai hospital.

Arriving in the eating disorders diagnosis center, Xuanxuan was given a new patient survey. “I remember, there were a few questions: ‘I want to commit suicide.’ ‘I want to run away from home.’ ‘I’m depressed.’ ‘I don’t want to eat,’” she wrote. “I answered them honestly one by one.”

However, anorexics usually will not seek treatment; it’s one of the characteristics of the disease, explains Dr. Chen Jue, director of the Eating Disorder Diagnosis and Treatment Center at the Shanghai Mental Health Center (SMHC).

Patients typically come to Dr. Chen after many detours. It usually takes a parent to see that their child is very thin. They often think it’s a digestive problem, or perhaps paused menstruation. They may consult a physician, gastroenterologist, or gynecologist, without noticing any improvement. A more knowledgeable doctor may suggest that it’s a psychological disease, and transfer them to an eating disorder specialist.

The SMHC, one of a handful of teams treating eating disorders since the early 2000s, is struggling to keep up with the surging demand.

Whereas the center rarely saw eating disorders just 20 years ago, it treated nearly 1,000 eating disorder outpatients in 2015. By 2018, the number grew to 1,916, for a year-on-year increase of over 20 percent. The number of inpatients also nearly tripled in the last four years, from 54 patients residing full-time at the center in 2015 to 145 in 2019.

“China’s entire psychological treatment system is not good enough to begin with; let’s not even mention treatment for eating disorders,” Dr. Chen tells TWOC over the phone at 11 p.m., after a day packed with clinical work and meetings. “There are far, far from enough specialists who are trained in eating disorders.”

A weight-loss camp for performing arts students in Shandong serves tomatoes for lunch

Patients travel from all over the country to seek treatment from the country’s few but growing number of eating disorder centers and experts. “Families come down from Shenzhen to Hong Kong on weekends to seek help from me. One or two even flew from Beijing,” says Ma of her family therapy practice in Hong Kong. “I keep telling them they should find someone on the mainland, but they keep saying they can’t find the family services that they rely on.”

In Beijing, the Peking University Sixth Hospital opened the country’s first and largest closed ward for eating disorders in 2011, treating about 250 inpatients a year. A few experts at hospitals in Nanjing, Chengdu, Qingdao, and Dalian have started taking eating disorder patients, although without the resources to open a specialized facility.

There are still numerous hurdles to a streamlined national system of treatment, and this ultimately costs lives. Many patients arrive too late, caught in a loop of referrals: “Once we transferred a severely ill patient to the general hospital to try and save her life, but she was gone within three days,” says Dr. Chen. An expanded screening and referral system between different hospital departments is crucial to getting patients into treatment quickly.

Cost of treatment is also a barrier for families. China’s national health insurance covers a hospital stay of 40 to 50 days, after which the cost of treatment soars to over 25,000 RMB per month at the SMHC. Yet it typically takes two to three months for patients to change their cognition, emotions, and behavior; anorexics typically regain weight over six months.

“I hope the country can understand that mental disorders are slow and chronic diseases that are difficult to treat, and so the government can consider the average length of stay, and cost for families within the medical insurance policy,” says Dr. Chen. In many cases, at least one parent has to stop working to care for the child after hospitalization and manage his or her diet, adding to the financial burden.

The broadest challenge is a public lack of awareness toward mental illnesses and eating disorders. China’s first official Blue Book of Mental Health, published in 2019 by the Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, found that nearly three-quarters of Chinese felt they don’t have access to psychological counseling, and education about how to prevent and treat mental illnesses was rated one of the most urgent mental health needs.

The SMHC is beginning to educate parents. This spring, the center held four free online lectures for families of eating disorder patients by leading specialists and psychologists, with 800 families tuning in.

Last year, the Shanghai Science and Technology Press translated and published the book Help Your Teenager Beat an Eating Disorder by James Lock, director of the Stanford Eating Disorder Program. The first Chinese print of 3,000 copies sold out within two months.

“We need people to know this is a problem, that they can come to see specialists, can be hospitalized, can stay in our wards, can be diagnosed and treated professionally. We need to encourage more people on this path,” Dr. Chen argues.

While there are no official statistics, Dr. Chen estimates that the rate of those with eating disorders who seek treatment in China is not more than 10 percent.

Most gyms lack early detection and referral systems for eating disorders

As hospitals rush to provide timely and effective medical treatment, a larger battle rages on in the cultural sphere, where the mass media and social media perpetuate unhealthy and unrealistic beauty standards that have become toxic sustenance to young women.

“For girls, being fat is a crime,” actress Shu Qi declared on TV in 2015. On Weibo, challenges such as the “A4 waist” exploded in 2016, inviting women to pose for selfies with a sheet of printer paper in front of their body, with the goal of proving that their waist is slim enough to be covered by the paper. Other versions of this challenge go viral each year, from the “4-centimeter wrist” to the “clavicle coin,” in which one balances a coin or another object on one’s collarbone.

On Baidu Forums, TWOC recently found four QR codes redirecting to WeChat groups for “rabbits,” a slang term for bulimics based on the identical pronunciation of “rabbit” and “vomit” in Chinese. They were advertised in Baidu’s “pro-bulimia” forum, an online community of 50,000 users who trade vomiting techniques, sell accessories for draining the stomach, and offer emotional “support” for behaviors such as hiding their habits from their family.

The forum has over 5.5 million posts at the time of writing, far outpacing the 1.2 million posts in the bulimia recovery forum, and the mere 302,000 in the anorexia recovery forum.

By scanning these QR codes, TWOC was invited to join four WeChat groups. Two were dedicated to discussions of vomiting tactics, while two others were to support those recovering from eating disorders. In one 24-hour period, one pro-bulimia group accrued 2,241 messages, while the recovery groups had 662 and 654.

“Fellow rabbits, I want to ask: I drank a lot of water, added a bit of salt, and chewed my food thinly, but it won’t come up no matter how I press [on vomit reflex areas],” begins one message in a pro-bulimia group, seeking advice on how to vomit more effectively. In another group, members share pictures of their meals and report whether or not it came back up cleanly.

In the pro-bulimia WeChat group “Little Fairy Ladies,” moderator “Aime” advised group members to use a tube to induce the vomit reflex rather than using their fingers. “Beginners always use their hands, but experts use tubes, which are more efficient and healthier,” she declares in a voice message one weekday.

On a Sunday, she posts in her personal WeChat feed that she has sold over 100 plastic tubes this week, shipping them across the country. In recent years, many plastic tube vendors have been removed from e-commerce platforms like Taobao, and instead take the trade into informal social media channels like WeChat.

“How can a tube be healthy?” Dr. Chen rails over the phone, outlining the health risks of causing friction in one’s esophagus and stomach, and removing electrolytes from one’s body.

The “A4 waist” challenge requires women to maintain waists less than the width of printer paper

Better regulation is needed to nip unhealthy habits in the bud, she says. Firstly, she suggests that government should require gyms to have basic indicators concerning the health of its members, and those whose body-mass index (BMI) shows they are malnourished should be required to continue under the supervision of a nutritionist.

Secondly, the regulation of diet pills is “terrible,” as “there are all kinds of diet pills on the market, and anyone can buy any amount, causing a number of widely reported deaths each year.” Dr. Chen also condemns the presence of binge-eating livestreams, many of whose stars have been discovered to induce vomiting afterward, amounting to a cultural glamorization of disordered eating.

Although fewer in number and frequency, those recovering from eating disorders have also taken to the internet to support one another. A college student known as “Lu” frequently posts vlogs to her over 5,200 followers under the Weibo hashtag “Eating Disorder Recovery Notes,” which has 6.5 million reads. Under the hashtag, many users encourage one another to seek professional medical treatment, and share their steps along recovery, from regrowing a full head of hair to regaining menstruation.

“Makeup bloggers say that if you don’t buy lipstick, you’re not a woman. Fitness bloggers ask, why don’t you have an A4 waistline in the summer?” wrote Lu on Weibo on April 1. “These ‘standards’ are not biological, but social, and are attached to women by society to emphasize the social value of women as reproductive tools.”

“I think this is why people believe that feminism can play a positive role in the rehabilitation of women’s eating disorders—because feminism regards women as people,” wrote Lu.

“Young people can only see their thinness, they cannot see the damage to their body, even trading their life,” says Dr. Chen. “This is how the disease works. They will come to seek knowledge and treatment only when it’s very painful.”

“I now think that the real cure for anorexia is love,” wrote Xuanxuan, now steadily regaining weight on the way to recovery. “It is my love for myself, my life, my family.”

Hunger Games is a story from our issue, “Contagion.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.