As tai chi evolves from a combat style to an exercise for retirees, its practitioners wonder about the future of this ancient martial art

Jack Ma may be a middle-aged e-commerce magnate, but his martial artistry is undisputed, at least according to the film Gong Shou Dao (《功守道》). In the 20-minute short, which translates as The Way of Defense and Attack, “Master” Ma beats off seasoned fighters played by Jet Li, Donnie Yen, and Wu Jing, before waking up outside a police station—it was all a dream.

The plot of Ma’s vanity project seems an apt metaphor for the modern misfortunes of tai chi, the ancient martial art that influences the mogul’s fighting style in the film. Leading proponents of the age-old discipline have lately brought embarrassment to its name: In the fall of 2017, self-proclaimed “Thunder style” master Wei Lei, also known as Lei Lei, claimed to possess “internal powers,” and repeatedly sought matches with other martial artists, such as MMA fighter Xu Xiaodong, only to lose swiftly and publicly.

“It’s hard to believe this is the same as those magic martial arts on films and TV,” remarks 25-year-old Ms. Liu, as she watches a group of mostly elderly practitioners move in slow-motion at Beijing’s Zuojiazhuang Park. She dubs Gong Shou Dao “Jack Ma’s dream of kung fu.” Among the practitioners this late December morning is Ms. Han, a 61-year-old retiree who, immersed in her art, moves like a ballerina, ignoring the bitter cold and numerous bystanders.

“The current version of tai chi…is no longer for fighting,” a tearful Lei Lei told a TV crew after his most recent spectacular defeat. “It’s only for fitness.” Tai chi’s popularity with pensioners suggests this is widely understood by many, but doesn’t explain why its so-called “masters” bear little resemblance to the sages of cinematic tradition—nor why the practice is now dogged by accusations of fraud.

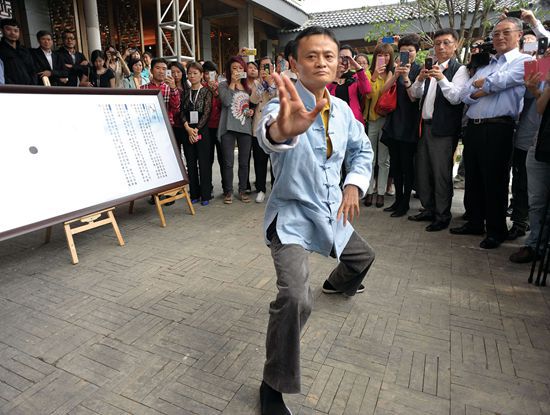

Jack Ma, a tai chi practitioner for over 30 years, shows off his skills at the opening of a tai chi center he cofounded with Jet Li

According to popular culture, tai chi (also called taiji, short for taijiquan) was invented by the legendary Daoist master and alchemist Zhang Junbao. Better known in China by his monastic name Zhang Sanfeng (张三丰), he founded the Wudang Sect and so-called “internal” martial arts.

This story, however, is much disputed in academic and martial arts communities, since there is doubt about when—or even if—Zhang Sanfeng lived. For example, some Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing literature states that the master-turned-immortal might have been at large through the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties, a lifespan of over 200 years. Nevertheless, both Wudang and Zhang Sanfeng tai chi are still widely practiced today.

A more plausible origin can be traced back to the Ming general Chen Wangting, who is said to have blended skills passed down from his ancestor Chen Bu and the late general Qi Jiguang to create “Chen style” tai chi. Added to the mix were the Daoist principle of taiji or “supreme ultimate potential,” the basis of the philosophy of yin and yang; the Five Elements (metal, wood, water, fire, earth) of the The Book of Changes; the principles of “channels” and renewal from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM); and the breathing methods of qigong.

Chen’s ancestral Chenjiagou village in Wenxian, Henan province, is now known as the “birthplace of tai chi.” In the 1980s, Wenxian became the first county in the province to accept foreign visitors, as tai chi enthusiasts around the world clamored to learn from the source. The village still draws thousands of tourists and students from China and abroad every year.

In the early 1800s, Yang Luchan, a child slave in Chenjiagou, became the first non-family known member to be taught the Chens’ skills, which he used to found the Yang style. Later styles, including Wu, Sun, and He, were developed in a similar way and named after their respective founders; each has its own characteristics. For example, compared with Chen-style tai chi, Yang features smaller and softer movements. As an internal martial art, tai chi generally focuses on elements such as mind, spirit, and qi (“vital energy”), relying on relaxation rather than physical strength to facilitate movement.

When Ms. Han finishes her set in Zuojiazhuang Park, she comes over to set the record straight about both Ms. Liu’s and Lei Lei’s doubts. “Of course, tai chi is a combative technique,” she tells TWOC. “That was its main function in the ‘cold weapon’ era,” before gunpowder was invented. Certainly, the legends say it’s so: Yang’s teacher, sixth-generation master Chen Changxing, worked as an armed escort, using his skills to fight off bandits. When Yang himself went to Beijing to teach tai chi, he defeated all challengers to win the title “Invincible Yang.”

Such glories, though, are harder to come by in modern China. Lei Lei’s infamous 2017 defeat by Xu in under 20 seconds was embarrassing, but the responses from other masters made matters worse. Incensed by Xu’s victory speech, in which the MMA fighter denounced his opponent as fraudulent and taunted other challengers, tai chi master Yan Fang released a dubious video in which she sent a disciple flying without touching him.

Award-winning practitioner Wang Zhanhai, the 12th-generation “inheritor” of the Chen style, tried to showcase tai chi’s practical use by winning a televised tussle against three rugby players. After suspicions were raised, though, one of the players apologized and admitted the footage was staged.

Chen Ziqiang (third from left) tours the world offering tai chi training each year

Born in 1977, Chen Ziqiang is a 20th-generation descendent of Chen Wangting, and a national and world champion who has been studying his family’s style since he was 3 years old. Now head coach at the Chenjiagou Taichi Academy, Chen believes the Xu-Lei fight was a planned publicity stunt, as the two already knew each other. Although Chen was in Europe at the time, he tells TWOC that several of his students went on to challenge Xu, but Xu refused them all and instead called the police.

“Tai chi can definitely be applied in practical fighting, but fewer people in modern times have such a need,” Chen declares. “Over 99 percent of practitioners learn tai chi for health concerns.” Although he admits his prowess is nothing like the masters of legend, “we’re trained with certain techniques to be quicker both in sense and movement.” Chen estimates that he can handle, at most, “five ordinary gangsters” who do not know any martial arts.

However, he also doesn’t see any necessity to prove tai chi’s fighting application: “We’re busy coaching, and I only want to pass on my family’s martial art.”

The authorities share Chen’s attitude. After the PRC’s founding in 1949, the government went to great effort to quash the fighting aspect of arts like Chen’s. When the National Sports Committee (NSC) was established in November 1952, martial arts groups were forbidden from forming at state-owned companies, factories, and mines to avoid disruption or dissent.

Instead, these combative arts were promoted as sports, exercise, or performance: Form and standardized movements were emphasized, and a set of detailed rules were formulated to govern the contents and technical criteria of each style.

Well-known martial artists adapted the Yang style, the most popular at the time, into a simplified 24-step program by adding acrobatic movements in accordance with the sports system of the Soviet Union, which emphasized “labor and national defense preparation.” Attempts to mesh Marxist-Leninism with quasi-scientific “brain movement theory” established tai chi’s role within politically correct healthcare; the yin-yang symbol was even said to represent the contradictions of dialectical materialism.

Contestants practice tai chi at the opening ceremony of an international competition in Rizhao, Shandong

The promotion was successful enough that it is estimated over 300 million people today practice tai chi in 150 countries worldwide.

Tai chi’s current popularity in China is partly due to the low requirements in terms of cost, time, and venue, at least at the amateur level. Han and her friend Ma Shuhua, a 66-year-old retired music teacher and dancer, both started doing tai chi in their 40s because the flexible nature of the exercise didn’t detract from their work or household duties. “It makes me healthier,” Han believes. “I seldom go to any hospital or pharmacy.” As evidence, she extends her hand, the warmth of which is an indication of robust qi circulation, according to TCM.

Ma emphasizes the tranquility that tai chi brings. “During practice, we have to employ the mind to control qi and expression from within. Then, our hearts will be calm, and we’ll feel happy and joyful.”

Although schools from kindergarten to college provide tai chi training as an optional or compulsory PE course, younger generations have shown less interest than Ma or Han’s. Chen Cen, a 29-year-old HR manager in Shenzhen, had signed up for a tai chi course for PE credits in college. “I was enchanted by Zhang Sanfeng’s powerful kung fu on TV, but I learned nothing from the course after one semester, except the teacher saying, ‘Cut a watermelon into halves, one for you and one for me,’” she says, repeating the mnemonic that beginners use to learn hand motions.

Since she frequently works overtime, Chen Cen goes to the gym three times a week to deal with the boredom and health issues associated with her office job. While she sympathizes with tai chi’s appeal among the elderly, her preferred exercise is yoga. “In the ‘fast food’ era, young people pursue quick visible effects, and tai chi cannot keep practitioners fit as fitness programs do, or cultivate their appearance like yoga,” she believes. “Besides, they can’t really experience the joy of tai chi without a good teacher and peers who practice together.”

Tai chi has been promoted as an exercise for schoolchildren nationwide

Ms. Wang, an employee at a Beijing tai chi school who gave her surname only (“our school doesn’t comment on the controversy of tai chi’s practical fighting application”), tells TWOC that her teenaged pupils have varying expectations, from fitness, to learning about traditional Chinese culture, to acquiring combat techniques. Some, though, “come because their parents sent them, and complain, ‘It isn’t cool at all.’”

Ma agrees that the young are “too eager for quick success and instant benefits…as the saying goes, ‘ten years of practice goes into one minute of performance,’” she quotes. “This would hardly be acceptable to the younger generation.” Han doesn’t believe tai chi is an “old person’s exercise,” claiming to have seen plenty of teenaged and middle-aged teams when she participated in competitions, but admits that she doesn’t know any youngsters in the art herself. “They are too busy.”

Whether tai chi can maintain its prestige and popularity in such a fast-changing China is not simply an idle question. After all, as one movie critic remarked after watching Gong Shou Dao, “All martial arts can be defeated, except wealth.” Some serious practitioners maintain tai chi can only survive if it stays true to its roots. In the wake of the Lei-Xu controversy, clan descendent Chen Bihua told news app The Cover that he had mixed feelings about the increased attention on tai chi. “Of course, it’s good for tai chi to develop…but today’s tai chi no longer has the same flavor,” he declared. “Many people just award the title ‘master’ to themselves…but even Chen Changxing, as legendary as he was, was known only as ‘practitioner’ in our lineage records.”

Chen Bihua says his students undergo rigorous family background checks before they’re accepted, and must follow the clan’s traditions, or “you won’t get to learn the real thing.”

Amateurs, though, feel that the art must expand and evolve. “India has already made their yoga a worldwide heritage item, and it’s a pity tai chi hasn’t gotten the same respect, when it’s such a symbol of Chinese culture,” says Ma. “I won’t comment on the other stuff; I just want say that after practicing 20 years, I’ve never been seriously ill…I think I’m making a positive contribution to the nation’s medical bills.”

Tai Chi Hustle is a story from our issue, “Home Bound.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.