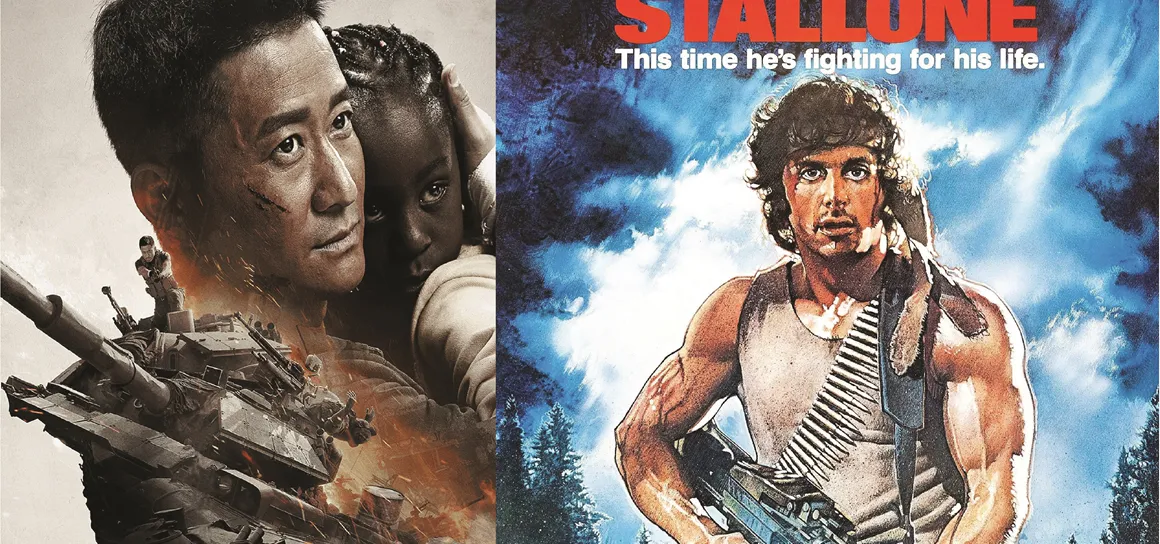

With Wolf Warrior 2 at the Oscars, remembering when Rambo was all the rage in china

On March 4—sex scandals notwithstanding—Hollywood’s elite will assemble at Hollywood’s Dolby Theater for the 90th Academy Awards, where China has pinned its own Oscar hopes on an unlikely contender.

Despite making 851.6 million USD with its flag-waving depiction of Chinese foreign policy, Wolf Warrior 2 is not an obvious official pick for Best Foreign Film category (past nominees included Zhang Yimou’s wartime epic Flowers of Nanjing and Feng Xiaogang’s Back to 1942, a harrowing depiction of famine in Henan).

“Being a sequel and an action film with an astonishingly high body count may weigh against the film,” Variety noted. Wolf Warrior 2 has been criticized for both its violence and tactless depiction of the unnamed African country in which the film takes place. This has prompted many to compare the film’s patriotic protagonist, Wu Jing, with the equally pugilistic John Rambo, hero of First Blood and numerous sequels including 2008’s Rambo.

“The Rambo movies personified America’s ability to accept its Vietnam veteran community and misadventure in Vietnam, and even for the direct smack-down confrontation that Americans longed for against their Cold War adversary, the Soviet Union,” observed The Diplomat. “Chinese are leaning not only into a Wolf Warrior that is responsive, globally-focused, and bent on protecting Chinese nationals and interests, but also a People’s Liberation Army that is as well.” Chinese blogger Ma Tianjie noted “the whole movie can be seen as a convenient set-up to show off the might of a rising superpower.”

What’s somewhat forgotten is the small role the 1982 original First Blood played in the history of Chinese cinema. In 1985, First Blood became—barring a couple of embassy film festivals—the first modern American movie to be shown in China. It was a coup for Hollywood executives: A tickets may have only cost a few cents (6 mao), but the Chinese box-office could count annual receipts of over 10 billion at the time, and the mainland market was viewed as a long game.

The Stallone flick ran for weeks in theatres around the country—the original Rambo’s harsh criticism of capitalism’s treatment of its proletarian veterans seemingly struck a socialist chord with censors at the time, despite its frequent and graphic violence. But others suggested the reason that the film was allowed was a simple matter of economics. At the time, the China Film Group rarely paid more than 10,000 USD for overseas distribution rights; some speculated that the studio offered a bargain price. If so, it paid off: Over a nine-day run in 21 cinemas in Beijing, the film’s tickets were scalped at several times their original price, and over a million curious cinemagoers queued to see its unique depiction of an unruly individual’s war on society.

Audiences were reportedly thrilled at the plot and special effects (“there were loud gasps” when Stallone debuted his bare and considerably bulky chest, according to one foreign report), but others were left shaken by the experience. “It is thrilling, it is awesome, but it is not beautiful,” wrote one critic on Dianyin.com. “The worship of the so-called noble savage is nothing more than the glorification of bandits, murderers, and arsonists.” The film defied “our national aesthetics, our social system, and our political system.”

Hardliners in government seemed to agree, and First Blood was yanked after a couple of months. As the surprise success of Wolf Warrior 2 showed, it’s often hard to predict the taste of both Chinese audiences and censors. A year after First Blood, the 1978 Superman debuted in Beijing. It lasted only a day: A review in the Beijing Evening News denounced the film, and a scene in which Superman circles the Statue of Liberty, as symptomatic of “a narcotic the capitalist class gives itself to cast off its serious crises.” In November this year, though, the latest in the DC superhero franchise, Justice League, safely debuted in China with a 52 million USD opening weekend.

Lone Wolves is a story from our issue, “Fast Forward.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.