The “post-90s” generation in government—from our cover story

The Propaganda Office of Jiande, Zhejiang province, a mountain town with a population of 500,000, operates an unofficial graveyard shift from 10 p.m., as netizens around China settle in for a night of browsing.

The shift has a staff of one: Cai Haoyang, aged 26. A government employee in Jiande for the last three years, Cai is seemingly on a quest to make his remote town go viral. A steady trickle of tourists has been coming up the mountains ever since a video of the area’s wild cherry blossoms was picked up by Zhejiang TV in early 2017. Since then, Cai has kept the momentum going by offering homes for free to urban investors on Weibo, and being the writer, director, and groom in a mock “water wedding” staged at a nearby fishing village last spring.

Older colleagues praise Jiande’s jiulinghou propaganda officer as a true patriot. Cai gave up a prosperous middle-class city life to serve the people, according to a short profile published in his local newspaper. Cai actually had mixed feelings: “In college, I wanted work in a corporation—at Huawei, like many of my classmates,” he tells TWOC. “But my parents wanted me to take the civil service exam.”

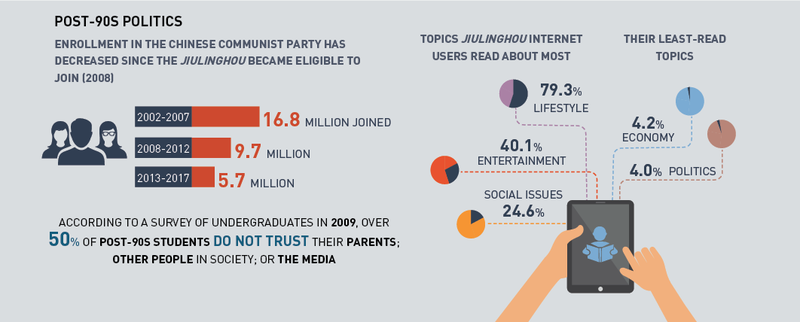

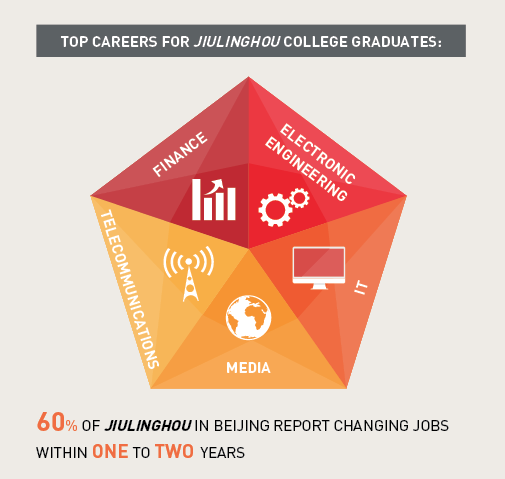

According to official data, the competition in China’s annual qualifying exams for civil servants is at an all-time high: Almost 1.66 million examinees signed up for last December’s sitting. However, the proportion of withdrawals is also increasing, suggesting that real interest in this career path may be waning. Around 526,000 examinees dropped out in 2017, almost a third of the total registered. A 2016 survey by Shanghai Open University and Fudan University indicated that only eight percent of that year’s graduating students wanted to become civil servants—a distant fifth choice behind multinationals (23 percent), entrepreneurship (21 percent), and private and state-owned enterprises (SOEs; 20 percent each).

Cai notes that, until last fall, his departments had no other employees of his age: “It’s no longer considered a ‘golden rice bowl,’” he says, embellishing on the “iron rice bowl” metaphor once applied to stable—if monotonous—state-sector jobs up until the 1990s. Cai’s generation, however, was born in the decade when many SOEs and government agencies were being dismantled or downsized. In 1992 alone, about 12,000 civil servants left to join or start private companies, while another 10 million took unpaid leave; Guangzhou real estate tycoon Pan Weiming and Liu Chuanzhi, founder of Lenovo, are two who public employees flourished after quitting.

A few young colleagues Cai had at the start of his job have also since quit. “They wanted to realize their dreams,” he says. “Here, work is the same every day. Our generation likes a bit more freedom.” In the 2016 survey, students picked “room for advancement,” “honing one’s skills,” and “personal interest” as the top three criteria for choosing a job.

With a scarcity of new blood, government departments try to highlight the idealism of individual “post-90s” hires—Cai aside, there’s Wang Xue, an Anhui vice-mayor who takes vintage self-portraits in her town’s scenic spots for tourism promotion. Zheng Ruizhen, deputy chief of a Shaanxi county, is nicknamed China’s “internet celebrity cadre” for her photogenic looks and Peking University pedigree, but cynical commenters point out Zheng got her position through a co-op with her PhD program, and “just stands next to the real official while he makes his rounds.” One post-90s individual, quoted in The Paper, characterized government jobs as not only “boring” but “depressing”: “They create nothing, and face so many restraints and complex relationships.”

In April 2017, while anti-graft drama In the Name of the People was still on air, a purported post-90s civil servant of a rural county made minor waves by blogging that her supervisor had fobbed off a blind man pleading for his benefits, then chastised her for volunteering to help. “Seeing the words ‘To Serve the People’ on the entrance [of the office],” she wrote, “I felt extremely bitter.”

Cai is adamant that no such “incidents” have occurred where he works, but admits that part of learning the ropes at his job is finding out what problems he isn’t able to solve. “As a young employee, you always wants to achieve things, but the more you do, the more risk there is of mistakes, so you need guidance from more experienced colleagues and leaders. You are their apprentice—for several years you learn how they do things and what to say.”

Although the civil service is no longer a place for idealists—and wasn’t even his first choice—Cai still finds it as viable career for his generation. “I do things that are meaningful to society, but also meaningful to me personally,” he says. “I’ve been responsible for new media ever since I started working here; I’m good at it. I’ve had many essays that got tens of thousands of clicks.”

These interests, however, have to take place on his own time—after a long day of driving to meetings and training sessions around the district, drafting official press releases, or being roused at 5 a.m. to perform routine seasonal labor like flood or forest fire-prevention. Cai says he’s happy to do it all, at least for now:

“I’m young, so I can still handle it.”

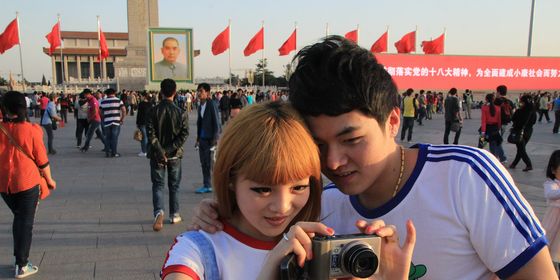

Cover photo of Cai Haoyang taking part in the traditional water wedding

The Noughty Nineties: The Bureaucrat is a story from our issue, “The Noughty Nineties.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.