A day in Dongjiao, the Hainan community where a single fruit is the source of everything

As the folklore in Hainan goes, coconuts have eyes. Before falling off its tree, a potentially deadly distance of up to 50 feet, an overripe nut peeps at passersby through the holes on its husk so it can avoid the innocent and aim only for the guilty.

On my first night in the Dongjiao Coconut Grove, Mrs. Pan, a farmer-turned-seller of souvenirs, relays this local wisdom to me in lilting, accented Mandarin. She reassures me that I have nothing to fear from the over 500,000 palms that populate one of Hainan’s oldest coconut plantations, located on a peninsula outside the city of Wenchang, on the island’s east coast.

“These ‘king coconuts’ are from our own ancestors’ trees; we’ve farmed them for 100 years without getting hit,” she beams. But looking up at these monarchs on their perch, growing so densely that they blot out the light with their overlapping leaves, I am not so sure. We are in their country.

There was a time in the not-so-recent past when almost all of China’s southernmost province could be called coconut country. Even today, when former plantations and wild groves have given way to sprawling investment properties and high-end resorts, the palm is still ubiquitous along any road and beachside of the island. In some sense, it’s the world’s tallest invasive species. The common theory states that coconuts (technically a “drupe,” rather than a nut) propagated to all the tropical regions of the world by simply falling off their trees, rolling into the ocean, and catching the current to plant themselves on the next beach.

It’s one of the few types of vegetation that has managed to establish itself in the shallow, storm-pelted soil of Hainan. According to Mrs. Pan, her community produces little of its own food today—just a few varieties of vegetables grown in the elaborately irrigated fields seen on the way to Dongjiao, bracketed on all sides by more coconut groves. Frequent typhoons and poor drainage kill most rival plants that try to set up camp. Coconut palms, on the other hand, can survive out here without fertilizer.

When one drives into Dongjiao, hand-painted signs flash by, hypnotizing reminders of all the ways that coconut country lives off its signature fruit: pure coconut water, freshly cut; coconut milk pressed on demand; all-natural coconut hand-oil; coconut-stewed chicken—as seen on CCTV! —and two-for-one coconut-shell spoons, bowls, and statuettes; coconut-frond baskets. At a meeting of the Food and Agriculture Organization in the 1960s, scientists tallied 360 uses of the plant, from fronds to trunk to root. One almost has to agree that coconut-based criminal justice doesn’t sound so far-fetched.

Compared to all the other uses of the fruit, coconut tourism has a much shorter history, yet it has come to dwarf the others in importance to the local economy. The recent global mania for coconut water notwithstanding, farmers don’t make much more from selling the fruit than when tourism first developed on this coast in the early 1990s. For each coconut that’s shaved, frozen, and shipped from Dongjiao, a planter earns 1 to 2 RMB, depending on the variety—the same price for which a visitor could pick up a fresh coconut from the roadside in the early days. The 6 to 8 RMB per coconut paid by tourists today is the only real profit that growers make from direct sales, says Pan; that, and the symbolic capital of their “ancestors’ fruits” being enjoyed across the country.

In some ways, modern visitors’ fascination with coconuts harkens to the beginnings of the mainland’s relations with Hainan itself. Formally incorporated into the empire under the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (汉武帝), the southern territory was referred to as Zhuya (珠崖), literally “Pearl Cliffs,” for the pearls that were found on its coast. It was not known at the time that the territory was an island, nor how far south it stretched; for 700 years after its discovery, maps depicted Hainan as a coastline with occasional southward pockets where the armies made inroads against the aboriginal Li people, who fiercely guarded the mountainous interior. The jewelry worn by the Li supposedly gave rise to the island’s other ancient name, Dan’er (儋耳, “Heavy Ear”).

In the following millennium, the island’s role as a destination for exiled officials gave rise to its conflicting reputations: both a forsaken backwater, and a place of exotic and rare beauty. Disgraced minister Yang Yan of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) stood in the former position, writing en route to his lonely exile: “A distance of 10,000 li/ Thousands do not return/ The province of Ya/ To live there is to be at the gates of Hell.”

The opposite impression is given in the poem “Dan’er,” by the well-known Song (960 – 1279) literati Su Shi, at the time of whose exile the island was beginning to be known as Qiong (琼, “Jade”)—a nickname it retains today—for the white cliffs of one of its interior mountains. Watching a thunderstorm on the island at dusk, Su wrote,“Leaning on the railings, I enjoy nature’s spectacle/ A rainbow arches from the clouds/ A strong wind blows pleasantly from the sea…as I grow old, all I ask is not to go hungry/ In a valley of my own, nothing else is important.”

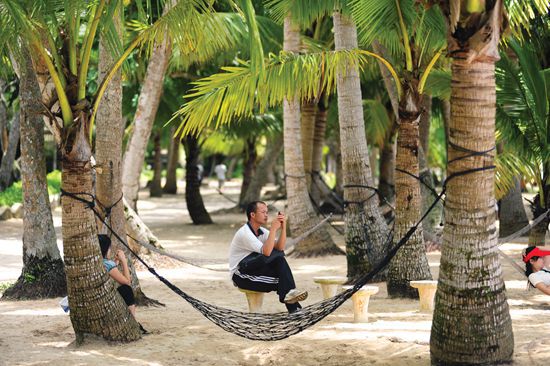

A tourist enjoying the cool afforded by the coconut’s shade in Dongjiao Coconut Grove (VCG)

Su never got his wish, as he was recalled to the court a mere three years later at the accession of a new emperor—but it’s difficult not to compare Su’s retirement plans to those of the visitors who flock to Hainan today. There are an estimated 1.1 million elderly among the province’s annual visitors—67 million last year. Among them are first-timers brought to the resorts on package tours, as well as “snowbirds” from northern China, who escape the winter weather each year to stay near the beaches for months at the time. Pan greets one as she walks in to browse the souvenirs—Dr. Liang, a retired physician from Sichuan province, who has been wintering here for more than 10 years.

“I’m not interested in coconut spoons anymore,” Dr. Liang announces, picking up one carved from sandalwood. On her stroll past the souvenir stands each morning, Dr. Liang has picked up more coconut and seashell memorabilia than she can count. Ten years ago, there hadn’t been any vendors, she tells me; the plantation was simply a set of adjoining villages where people farmed coconuts and fished on occasion. The farmer who now hosts her every winter was the first in his village to open his home to paying guests; back then, none of his neighbors understood why.

Nevertheless, local government officials had already sighted the Dongjiao’s natural potential as a vacationers’ paradise. In 1991, a year before the southern city of Sanya, now Hainan’s main tourist magnet, began building its first resorts in Yalong Bay, developers broke ground on the Prima Resort at the place where Dongjiao’s coconut groves ran into white-sand beaches. The construction was remarkably understated, and quite ecological for a tourist attraction of the 90s; the builders simply installed a pier, some wooden cabins among the palms, and a sprinkle of thatch-roof cabanas and hammocks on the beach. With a ready-made blue sea, white sands, and waving coconut trees, the resort looked like a tropical vacation cliché without even trying.

Yelin Bay, a popular tourist attraction inside the Dongjiao Coconut Grove (VCG)

In the early 2010s, though, the balmy winds changed. The development of Hainan took on a manic, deafening pace, fueled by greed and graft. Today, neither agriculture nor tourism is the main economy on this province. Instead, it derives over 50 percent of its GDP from property investment, ranking as one of China’s top three real-estate bubbles along with Beijing and Shanghai. In April 2018, the province placed a cap on property purchases across the whole island—and local officials have repeatedly been cited for corruption by the country’s feared Central Committee of Discipline Inspection since 2013 (to date, none of the guilty are known to have been hit by coconuts).

Wenchang’s officials made their own contribution to the saga in 2011, when construction began on a bridge and artificial island, 400 meters south of the Prima Resort. The project was reportedly for the dual purpose of stopping erosion of the coastline and providing yet more land to develop into a “world-class resort area” with hotels, theme park, and marina. Today, however, the 200-square-meter island is still empty, its only accomplishments being muddying the beach and water in front of the resort.

While they complain of the loss of their sea views, even locals aren’t sure what’s going to happen next. “I think they built this island to put apartments on it,” claims Dr. Liang’s host Mr. Wang, proprietor of an ad hoc retirement home for the snowbirds—more or less a large farmhouse with rooms for monthly rental, and mah jong tables in the corridors. “The sea used to be right outside my property; it was so beautiful. We fought this development for a long time, but what can we do?”

The answer, it seems, is to play up the local angle to any extent possible. The obstruction of Prima’s open sea views may have actually saved Dongjiao from the over-commercialized fate of Sanya’s Yalong and Haitang Bay—if those are indeed the only two options in today’s China—and this grove has become oddly frozen in time. To walk around the plantation is to pick one’s way around coconut trees and the mountains of the fruit stored in the clearings, ready to be taken to the chopping block and consumed—the varieties range from the earthy indigenous one known only as yezi (椰子, “coconut”), to the smoother-tasting, red-skinned Thai species.

Hainan farmers get to work peeling the coconuts, which can have hundreds of applications (VCG)

Coconuts are advertised and sold at every consumable stage, from the young and green to the old and fleshy—even coconuts that have sprouted. The latter is eaten as a local delicacy called “coconut egg”: The fibrous coconut flesh, made spongy by all the juice it soaks up as the coconut matures, is scooped out of the brown seed and consumed raw. There’s also an open-air diner in Dongjiao, beloved by the retirees rooming at the farmhouses nearby, that made its name stewing Wenchang’s signature chicken—a precursor to Singapore’s Hainan Chicken Rice—in milk pressed from grated coconut flesh. The nut-sweet broth, bubbling around ivory globules of meat and fat, brought CCTV documentary crews sniffing for a look in 2014.

On the bridge from Dongjiao back to the city, one passes by the future site of the Wenchang Coconut Carving Culture Expo Garden, now the workshop of a small factory promoting a thousand-year-old handicraft that the provincial heritage protection center warns is “in danger of extinction.” When the complex is finished, says Mrs. Ye, Mrs. Pan’s taxi-driver neighbor, farmers who produce their carvings in the more remote villages will finally have someplace to showcase their work, and teach workshops. “The roads are too difficult; it’s too far to take anyone to see [the craftsmen] in their homes now,” she says.

Mrs. Pan is plying her coconut trade again as I get ready to leave the plantation. “How about some coconut oil to take home to cook with? Some more coconut egg for the road?” she suggests. I point to a meal she’s prepared on her own table, and say I’d rather have what she’s having.

“This? Oh, this is baozi,” she smiles, gesticulating with a steamed bun. “I have coconut every day, so I wanted something different. Yesterday I had coconut. Today baozi.”

And tomorrow? “Tomorrow, I think I’ll make some noodles.”

Coconut Country is a story from our issue, “Vital Signs.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.