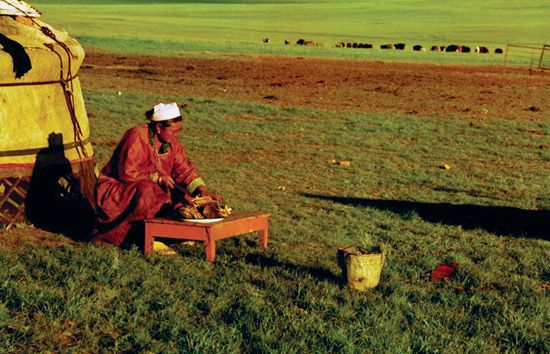

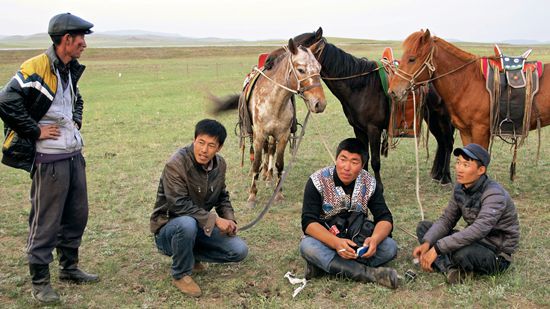

Rural realities don’t always match the mythic Mongolia of popular imagination

For those in need of a detox from the madness of urban life, the grasslands of Inner Mongolia have long been the place to go.

To inhabitants of increasingly congested cities, wide-open green pastures are picturesque sanctuaries. Whether breaking free from professional pressures, or letting go of the inanity of the newest Rap of China controversy, generations of travelers saddle the word caoyuan (草原, “grassland”) with—literally—pastoral longings to escape from the shackles of routine.

The locals have always known better.

As the Mongol adage goes, “The grasslands will always be the source of life and the root of creation.” This gains a darker, but no less impressive, layer of significance when one remembers that the caoyuan gave birth to 12th-century conqueror Genghis Khan and his army of nigh-invincible nomadic warriors. The Khan’s gargantuan empire, stretching from the Korean Peninsula to Hungary at its apex, brought down the Song dynasty (960 –1279).

The moral of the story? The grasslands are not only beautiful, but capable of bringing whole civilizations to heel.

The modern entertainment industry bears much responsibility for this idea of an animus-driven caoyuan. In Genghis Khan (1997), a Chinese-language film produced by the Inner Mongolia Film Studio, children practice archery by using a decapitated ox head as target. Wolf Totem (2015), a Sino-French adaptation of a best-selling novel by Jiang Rong, tells the story of how a Beijing university student, sent to Inner Mongolia during the Cultural Revolution, becomes enraptured by the steppes’ wolves, eventually trying to domesticate a cub.

Herders traditionally ate a dairy and meat-based diet, cooked on the open steppe or on stoves inside the ger

Meanwhile, caoyuange, or “grassland song,” remains a popular sub-genre of Chinese folk music, with singles such as Ji Ya’s “Grasslands Fateful Love” featuring male yodeling, excessively romantic lyrics (“let us turn into swans flying to the horizon, chase our love under the blue sky”), and a music video with young lovers holding hands as they gallop their steeds.

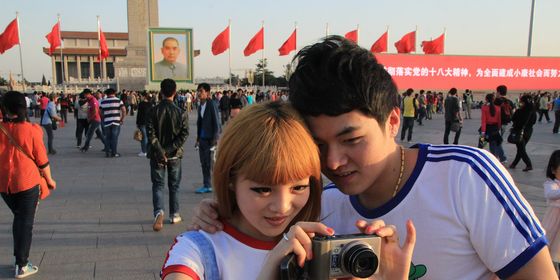

When I boarded an overnight nine-hour train one Thursday night from Beijing—there’s no high-speed rail yet to Hohhot, Inner Mongolia’s capital—it was with visions of sharing bowls of salty tea with hospitable horse-herders. In my dream of a caoyuan-induced catharsis, they were eager to share their skills and teach us how to ride. A hearty Friday evening meal at an excellent Hohhot restaurant, run by ethnic Mongolians, marked a promising start to the long weekend.

In retrospect, with a little more research, it would have been obvious that Inner Mongolia had more to offer than “holiday villages” outside Hohhot. For one, the ideal time to head over is not September, but during mid-July, when three-day naadam festivals are held throughout the region. Short for eriin gurvan naadam, or “the three games of men,” the naadam is full of tournaments in archery, wrestling, and horseback riding. Across the border in the country of Mongolia, the naadam is not only the most widely watched display of strength, but also commemorates the nation’s independence from the Republic of China in 1921.

Nomadic herders on the steppe have been offered compensation for resettling in towns Salty

Going to the games is essential for experiencing the local culture. The same applies to visiting the Mausoleum of Genghis Khan, located near Ordos and previously guarded by a Mongolian tribe, the Darkhads, for over half a millennium. Even today, around 30 Darkhads are officially employed by the mausoleum to watch over the site’s relics, keep worship candles lit, and stop the tourists from taking pictures where they’re not supposed to.

Without the wisdom of hindsight, however, we began Saturday morning with torrential rain descending upon Hohhot. My WeChat pinged with a message from our driver: Due to the “added difficulty” of driving in the downpour, his fee was going to increase from 200 to 300 RMB. My instinct was to back out, but it was too late; the return tickets were booked for the next day, and the driver, apparently assuming we had accepted his impromptu price hike, soon called to say he was just minutes away.

So we accepted the first rip-off of the weekend without protest. Our Han driver was extremely talkative, perhaps to sugarcoat the extra fee he’d surreptitiously extracted—though in all fairness, the roads were indeed pockmarked with potholes, mud, and sharp stones. Soon he was offering a lesson in basic Hohhot dialect (“pretty” is xiedang), and told us about the decline of Mongolian-language teaching in Inner Mongolia.

Inner Mongolia’s case seems to be identical to that of China’s other autonomous regions: The increasing competitiveness of China’s gaokao (university entrance examination) has led many ethnic Mongolian households to give up teaching the local language altogether. Although the vertical Mongolian script is visible all over Hohhot’s main roads—a contrast to the kite-like Cyrillic used by the country of Mongolia—only 17 percent of the region’s 25 million people are ethnically Mongolian. In spite of this, according to our driver, the region’s cultural practices and ethnic pride remain intact.

Our destination was the Anda Holiday Village, which was praised by a solitary review on travel app Mafengwo for its “hybrid tents,” cheap local delicacies, and (most importantly) hours of riding at discounted prices. Although the reviewer’s relentlessly flattering tone was suspicious, the dozens of high-resolution pictures that accompanied the text made us believe in this fairytale of the caoyuan.

“Traveler resorts” on the caoyuan typically offer yurt-shaped hotel rooms to visitors

The first thing we discovered on arrival was that the so-called Mongolian “yurt” was not the traditional ger (“home”) of the nomads. In popular imagination, the ger is a short circular structure made of wooden lattice, covered with waterproof furs and skins, providing a durable, comfortable, and quickly portable home to herders on the Central Asian steppes. By contrast, Anda’s yurts were whitewashed concrete structures with domed roofs, with a price per night that increased according to the number of modern amenities included. Ours had a bathroom, but no shower or flat-screen TV; at least, the overpriced igloo was a respite from the heavy rain. Like our driver, everyone working at the holiday village was ethnically Han.

Trapped indoors on a Saturday night, there was nothing for us to do except tune in to The Rap of China as usual. The key difference was that, at 2,000 meters above sea level, food delivery apps were unavailable. Traditionally, the center of a ger contains a stove beneath a ventilation hole in the roof, used simultaneously for heating and cooking; additionally, families will often hang animal carcasses indoors for curing, and put barrels of cheese and airag (fermented mare’s milk) beside the entrance.

These concrete distortions, though, were ideal only for cooking instant noodles, which we slurped down with a seasoning of boredom and regret before an early sleep.

**

Thirteen hours later, we woke to blue skies, warm sunlight, and undulating hills—a perfect Mongolian Sunday morning. We took a long walk through the grasslands, lying down every so often to enjoy the cool blades of grass. At one point we even took turns shouting gibberish at the top of our lungs; we had too much space to ourselves.

Soon, though, our bellies rumbled, indicating that it was time for lunch. Hoping to balance our starchy diet of the previous night, we walked towards a few (real) yurts, where a man was grilling some meat.

Salty tea, juicy meat on the bone, and hearty stews evoke the classic Mongolian meal

The caoyuan has a visible influence on Inner Mongolia’s gastronomy. Cattle fed on the large swaths of luscious green grass in the summer produce meat and dairy of a higher standard than livestock raised on processed feed. Tourists who are unaccustomed to the local dietary habits may feel overwhelmed by them; to withstand harsh winters on the steppe, Mongolian nomads often consume whole legs of roasted lamb and enormous slabs of boiled mutton, along with mugs of rich milk tea. This climate has also left Mongolian cuisine bereft of vegetable-based dishes, to say nothing of vegetarian fare.

The man running the makeshift restaurant listened to our order of a portion of mutton and vegetables. Sizing us up, long and hard, he came up with the astronomical figure of 300 RMB. We laughed in disbelief and told him we would try the canteen closer to our village. He responded that they would charge us double for the same thing (their cook was his mother’s cousin.)

Incredulous, but aware of how far we had strayed from our lodgings, we accepted the offer; like our driver, our cook had a smooth tongue, settling us in a tent and explaining that the leg meat on our tray was only half-done as this was how us “southerners” liked it. Moved as I was by his concern, my main anguish was directed at the plate of sugar-topped tomato (50 RMB) that accompanied it.

In the middle of our meal, the cook’s wife burst in to exclaim how happy she was to see two waidiren (“non-locals”) and present us with a gigantic flask of tea, disappearing before we had a chance to ask if it was on the house. Predictably, it wasn’t, and off went another 100 RMB from our bank accounts to this hospitable couple. (Both later claimed they wouldn’t have charged anything had we had simply returned the flask unopened.)

P Tea and pickled vegetables, all for the one-off bargain price of 250 RMB

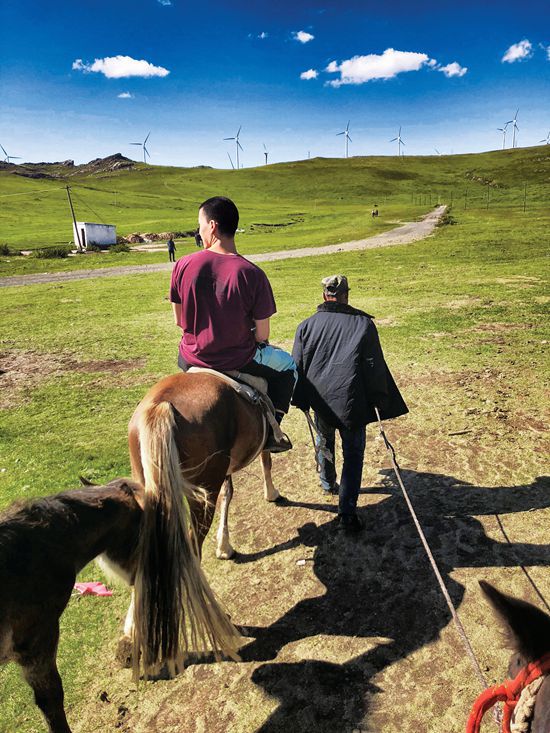

Already in low spirits, and with only a few hours left until the train back to Beijing, we were ready to leave, until our driver exclaimed that leaving the caoyuan without riding its horses would be a sacrilege. Noticing our skepticism, he claimed he would wrangle a bargain-basement price for a 10-minute ride: 150 RMB for two people. A quick search on Mafengwo proved that this offer was, indeed, 100 RMB lower than what most tourists were charged.

Under the logic that we would never come back to this caoyuan anyway, we accepted and made our way to the stables, where two pint-sized steeds and their hostler were ready on arrival.

On the back of this gentle beast, I found some small satisfaction in imagining myself part of Genghis Khan’s royal guard, surveying the battlefield as we debated whether to quarter or mercifully decapitate our enemies. This fantasy was cut short merely 100 meters later, when the handler suddenly stopped.

“This is as far as 150 RMB gets you,” he grunted.

I snapped out of my daydream and dismounted, ready to forget I had ever heard of this caoyuan. My girlfriend refused, though, protesting that this was not what had been agreed upon.

“Unless…you want to take the horse for a run,” he responded, a wide grin on his face.

Taking our stunned silence as a “yes,” he suddenly hopped on the horse I had dismounted, shouted “Hold on!” and took both beasts for a 30-second gallop—throughout which my girlfriend was screaming in fear—and finishing back at the stables, where it was time to pay up. We sent over the agreed 150 RMB, at which point the hostler, still grinning, said: “It’s another 150 for the gallop.”

On the way to getting ripped off big time

Scoffing at his demands, we made for the yurts, only to be met by a row of cross-armed hostlers blocking the way—this was clearly a well-rehearsed scam. Acknowledging defeat, I turned back and sent the man another 150 RMB with some sarcastic applause.

On the way back to Hohhot, the taxi driver did his best to appear oblivious, claiming that all the hostlers were greedy peasants and impossible to trust. Faking concern, he even offered to take us to a restaurant that his friend had opened, a place where one could eat a “proper” dinner for a “decent” price. Unwilling to risk any more money, we sternly turned down his offer and struck out for a KFC.

Over our reliably priced—if boring—meal, practically penniless, I reflected that perhaps we had been led astray by the illusion that simply being on the grassland was enough. In Inner Mongolia, the nostalgic caoyuan is increasingly hard to find. As China’s second-largest coal-producing region, Inner Mongolia is also the main global supplier of rare-earth metals, as well as the site of large natural gas reserves. Unregulated mining and industry have devastated the natural landscape and poisoned the livestock. Additionally, resettlement programs, often justified as protection of the grasslands from over-grazing, have forced most ethnic Mongolian nomads to give up their flocks for meager compensation.

These days, experienced travelers say, it’s only by hiring a trustworthy ethnic Mongolian guide that one can get lucky enough to find an “authentic” homestay—or a nomad family willing to receive paying guests on a wistful search for pastoral beauty.

On the other hand, scams and extortion are not experiences unique to Inner Mongolia or its artificial yurt villages. From the infamous “Snow Village” of Heilongjiang to Yunnan’s lush, tropical Lijiang, China’s domestic tourism industry is riddled with tales of tourists getting fleeced for meals, transportation, or simply taking photos of the great outdoors.

The frequency of such scams leads older travelers to seek safety in package tours, while the younger generation rents cars or campers for a stress-free, DIY travel experience. Yet in isolated and largely technology-free areas like the caoyuan, where police stations are absent and there’s no local economy to speak of, even these intrepid adventurers must rely on goods and services priced at the whim of the locals—who, in turn, have perhaps no other occupation than to milk their industry of escapism for all it’s worth.

Traveling to romanticized places like Inner Mongolia is often done with the hope of fleeing an increasingly materialist society. However, in China, the rural and remote communities can be where one often finds capitalism at its most predatory.

Perhaps ethnic Mongolian musician Tengger put it best, in an interview with Audio World magazine in 1993: “The lushness of the grassland belongs to the past.”

Out of Steppe is a story from our issue, “Curiosities and Quests.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.