A growing number of monasteries allow serious students to ascend to spiritual nirvana—even if only temporarily

Deep down, there are those of us who believe that, if we only lived without the modern scourges of globalization, urbanization and social media, we might become enlightened students of Aristotle or Buddha. We would become one with our “true self,” and close to the ultimate truth of the universe.

It’s only our decadent lifestyle that prevents us from having that choice. Or so the fantasy goes.

In recent years, the prevalence of meditation courses in China have meant that people no longer have to give up all earthy pleasures for a crack at attaining this kind of inner peace. Most of the modern courses are held in monasteries on scenic mountains, where you can wake up to the sound of ringing bells and birds chirping, and fall asleep to the soothing rhythm of cicadas. You can enjoy a minimalist life as envisaged in Henry Thoreau’s Walden, and still have access to tap water, electricity, and two or three good meals a day.

Most importantly, participants will not only be free from foul, loud urban lifestyles, but also the tyranny of the smartphone—turning in telecommunications devices is usually mandatory at the start of every course. (How can you get back to nature and experience any enlightment without a complete break from the hypnotized state of phone addiction?)

There are many kinds of course, and it’s better to know the differences before you pick one for yourself. Most in China fall into two genres: Buddhist and Daoist. The Daoist courses typically includes a unique fasting method called pigu (辟谷), literally “avoiding grains,” which, perhaps because of the potential risk to its student’s physical condition, are seldom offered to the general public, at least by Daoist monasteries. Most meditation courses featuring pigu are instead conducted by commercial enterprises “connected” with TCM and Daoist culture, and are therefore not recommended—with few exceptions, it’s very likely both your wallet and your body will pay a price.

If you are seriously into pigu, though, find a reliable, experienced master, preferably in a Daoist monastery in Mount Wudang or Mount Qingcheng, who might be willing to instruct, and remember to never push your body to extremes.

The Buddhist meditation courses mainly fall into the Chinese Buddhist and Vipassana forms of meditation. Although many take place in monastic surroundings, few are distinctly religious, but rather intended to cultivate a peaceful, observant, introspective mind.

For beginners, a weekend meditation course in the suburbs might suffice. Beijing’s reputable Longquan Monastery (龙泉寺) is one of the several that offer meditation courses during the year, conveniently concentrated on weekends, holidays, and throughout the summer. The duration varies from two days to a whole week.

“To enhance your ability to stay centered, concentrated, and calm, you are required to fill up a table daily that records how many footsteps you took from your dorm to the major prayer hall, and how many bites you took at breakfast,” Guo Ran, a regular attendant at the meditation retreat of Longquan Monastery, tells TWOC. “It is extremely beneficial to the samadhi [a state of union with the divine] of your mind. You need to follow the routine of the monastery and have conversations with well-learned monks. No matter the backgrounds of the attendants, everyone feel tremendously inspired and enlightened. When the course was over, I really missed it and didn’t want my phone back.”

However, such courses are not for those who desire more stern conditions. For most, the experience at Longquan Monastery is quite pampered, with organic vegetarian meals (sometimes featuring pizza and dessert), tea, calligraphy, and the company of friends with the same spiritual aspirations, while the dazuo (meditation done with legs folded) sessions will not be too demanding on stiff knees.

For those whose souls crave more solitude, there are places that can readily take loneliness to a whole new level. Monasteries that claim a strict lineage from ancient Zen masters fall into this genre: They not only forbid any phones, but usually any conversation throughout the course, even reading and writing. Unlike at Longquan Monastery, there will not be monks willing to discuss life and the universe. The students’ only task is to pay attention to their breathing and body, and try to find tranquility. These sessions usually last around 10 days, and require proper commitment, as leaving halfway through is usually enough to get one blackballed from future courses. Places that offer these courses include Erzu Chan Monastery (二祖禅寺), a monastery in Handan, Hebei province, that prides itself on being founded by the second master of the Chinese Chan sect, and Gu Guanyin Chan Monastery (古观音禅寺) at the foot of Mount Zhongnan.

The latter is most famous for a giant, 1,400-year-old gingko tree that takes on a golden hue in December and makes for a spectacular sight. However, it should be better known for its stern meditation courses. Following the peculiar Chinese Chan tradition, those who lose their upright posture during dazuo—an indication of absent-mindedness—will receive a heavy slap of the xiangban (香板, a long, thin board) on their shoulder, bringing their minds back to task.

Finally, for those who seek still more challenging conditions to rediscover their true self, Vipassana meditation (内观禅修) centers are the latest trend in fashionable meditation. The method claims to have ancient Indian roots, thousands of years older than Buddhism itself, but the most important canon it draws on is Buddhaghosa’s “Path of Purification,” a fifth-century work of Theravada Buddhism doctrine.

Most Vipassana meditation is known for its stern schedule, with stints on the meditation mat of up to eight hours a day, and a path to continuous concentration on the inner world full of physical and mental agony. For an authentic experience, meditation centers established by modern Vipassana teacher S. N. Goenka are recommended. Here, the surroundings and techniques are not distinctly Buddhist, but purport to eradicate mental impurities and cultivate self-awareness. However, Goenka’s centers in China are currently only open to those of Chinese nationality.

To get a Theravada experience, Dhammavihārī Forest Monaster (法住禅林), in the depth of the Xishuangbanna rainforest, is certainly an alternative.

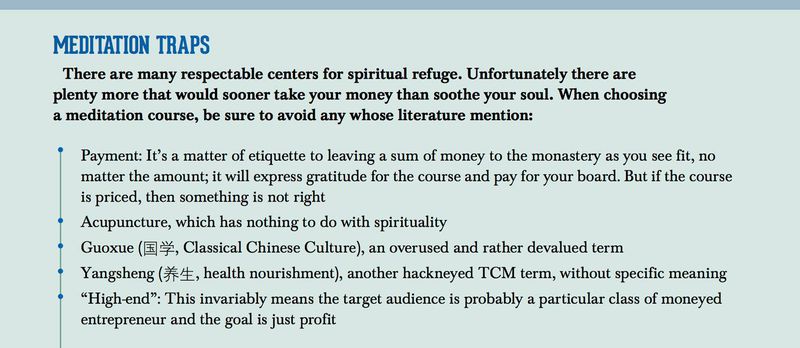

At their core, all these courses offer the same thing: a period of time in which each participant is compelled to do nothing but quietly sit with him or herself. It might seem a lot of trouble to go to just in order to stop hiding from oneself, but then again, that’s essentially what hermits want.

Into the Heavens is a story from our issue, “Down to Earth.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.