Deep in the mountains of Yunnan, Stefan Schomann joins the local schoolteacher who helped discover a new species of ape

Some 20 years ago, Li Jiahong heard a siren song deep in the forest, and answered it. Whenever local farmers told the schoolteacher that they had heard or even spotted “black monkeys,” he tried to track the creatures down.

It took him eight years before he eventually caught one on camera—a gibbon in the Gaoligong Mountains (高黎贡山) on the border of Myanmar. Slowly, the international research machinery cranked into gear. In May 2017, specialists from four continents published the results: Teacher “Gibbon” Li had discovered an entirely new species of ape.

Of course, he wasn’t alone. The American Journal of Primatology lists 15 anatomists, geneticists, taxonomists, and evolutionary biologists who were involved in the identification of Hoolock tianxing (天行 “Skywalker”) gibbon. A tribute to the I Ching, or Book of Changes, as well as the Jedi hero of Star Wars, the name is an acknowledgement of the gibbon’s mastery of acrobatics.

But the most important part of the name is its inconspicuous appendix, sp. nov, or species nova. Nowadays, most biologists are satisfied to discover an obscure cave moth or a deep-sea jellyfish; China’s discovery of a new ape could likely only be surpassed by finding a yeti or Martian.

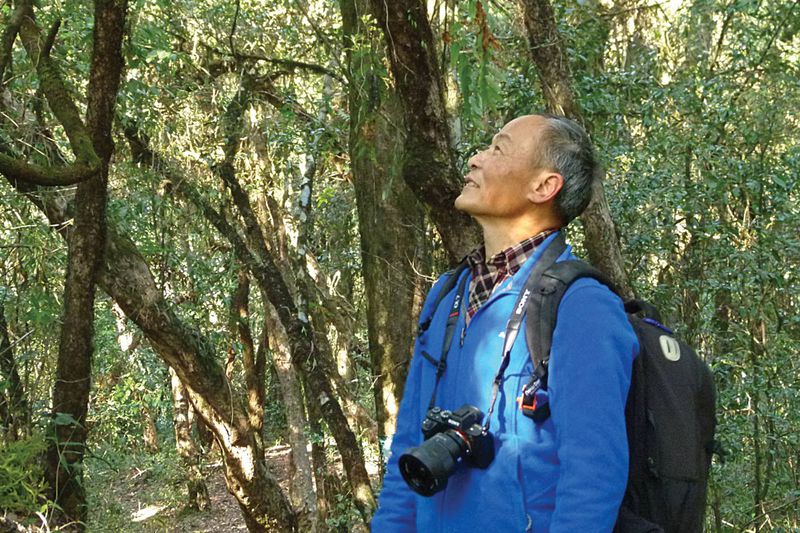

Li Jiahong vividly remembers the first time he saw a Skywalker gibbon (Stefan Schomann)

Li’s pictures had first found their way to Fan Peng-Fei, at the time an aspiring young wildlife biologist at Dali University. Fan tried to match the images to one of the two species of hoolock gibbons already reported in the area, but was unable to find a fit. Could it be a third species? During the lengthy process of examining the circumstantial evidence, Fan mobilized specialists in skulls, furs and teeth, examined excrement, and pulled up comparative examples from zoos in Bangladesh and museums in Philadelphia.

But it all started with Li Jiahong. We arrange to meet him in Baihua village (百花村), one of 11 stations in the Gaoligongshan National Nature Reserve that serve as staging posts for the wardens and fire services, and as contact points for visitors. What are the odds of meeting a Skywalker, I ask him? “That depends on whether the apes are in good humor,” Li replies with a twinkle. “And whether you are lucky.”

On our first day of searching, we are definitely not lucky. But I still enjoy prowling through the bush with “Gibbon” Li, a nature lover and autodidact, easygoing but professional. Li works for the park administration photographing and filming whatever he encounters, from giant squirrels to red pandas. He camps out in the bush several nights a month, explaining, “I am not afraid of the animals, but rather humans.” A teacher by training, he has also been instrumental in developing a “school of nature” for families and groups venturing up the mountains.

A female Skywalker gibbon (Li Jiahong)

In recent years, many new species have been discovered in the area, and some that were thought to have become extinct have been spotted anew. “Everywhere species decline,” remarks Li with a smile, “only here they increase.” He says that when the director of Yellowstone National Park visited recently, he confessed that this was the kind of nature he’d always dreamed about.

In the dim mountain forest, first impressions can seem rather confusing though. Everything sprouts, grows, blossoms, and rots simultaneously; you cannot see the trees for the wood. Magnolias and camellias try to outdo one another, laurel and theaceous plants get tangled up. The tree trunks seem to serve merely as a framework for tendrils, lichen, and lianas.

With a healthy dose of respect, Li points out bear scat on the wayside—some of his colleagues have been badly injured by Asian black bears, also known as “moon bears.” Up on the ridge, peasant women gather tea leaves. It was here that Li had his memorable first encounter with a Skywalker on the morning of May 16, 2005. “I heard their calls and ran uphill,” he recalls. “Two apes scrambled about in the treetops.” They fled, with Li in pursuit. When the male called out to his mate, she looked back—and Li shot the first picture of a Skywalker gibbon.

Later, he returned with Fan and his students. At first, the apes were very reclusive, because they were still occasionally hunted. But with Li’s patient tutelage, the animals gradually lost some of their fear of humans. On our trip, we had hoped for a similar leap of faith, but it seemed in vain. Nevertheless, Li is still confident that an encounter can be brought about.

Further west, a local man named Jiang Zi’an combs the forest. “He is one of my best men. I reckon he will find them,” Li tells me. Li recruited Jiang personally during one of his visits to the neighboring communities. He usually asks for “experienced men”—that is to say, experienced hunters, even though hunting has been officially banned in these parts for 20 years now. But having taught some of their children, Li has gained the local farmers’ trust and respect.

As nightfall approaches, we descend to one of the stations. Our accommodation is quite rustic: running water on the balcony, shared toilets in the yard, hard pallets for beds. The wife of one of the park wardens heads up the kitchen, another looks after the rooms. A ranger earns about 1,500 RMB a month, but the job is enhanced by the fact that his relatives might find employment with the park too. The uniform brings further prestige, even though the administration does not have sufficient means to outfit all 200 employees.

A male Skywalker gibbon selects a juicy fruit (Li Jiahong)

The next morning, breakfast seems to be dragging on. Some more noodles? No thanks. How about a papaya? Yes, please. Do you want to talk to some rangers? Maybe later. Would you like to have some time for yourself? No need for that. Finally, Li comes right out with it: “We have lost them.”

So instead, we decide to proceed to Baihualing (百花岭), about a hundred kilometres to the north, on the slopes of the Nu River valley. The village became known nationally after its residents took a high-ranking official to court for illegal logging in the communal forest during the 1990s. The occupants of Baihualing had other plans for their land. The farmers planted trees and bushes that attracted birds; birds attract bird-watchers, and they became the community’s main source of income. There are not too many places on earth where you can spot 40 to 60 different species of bird within a few hours. About 530 have been identified so far, and experts estimate that these forests might host around 600 species altogether—more than all of Europe.

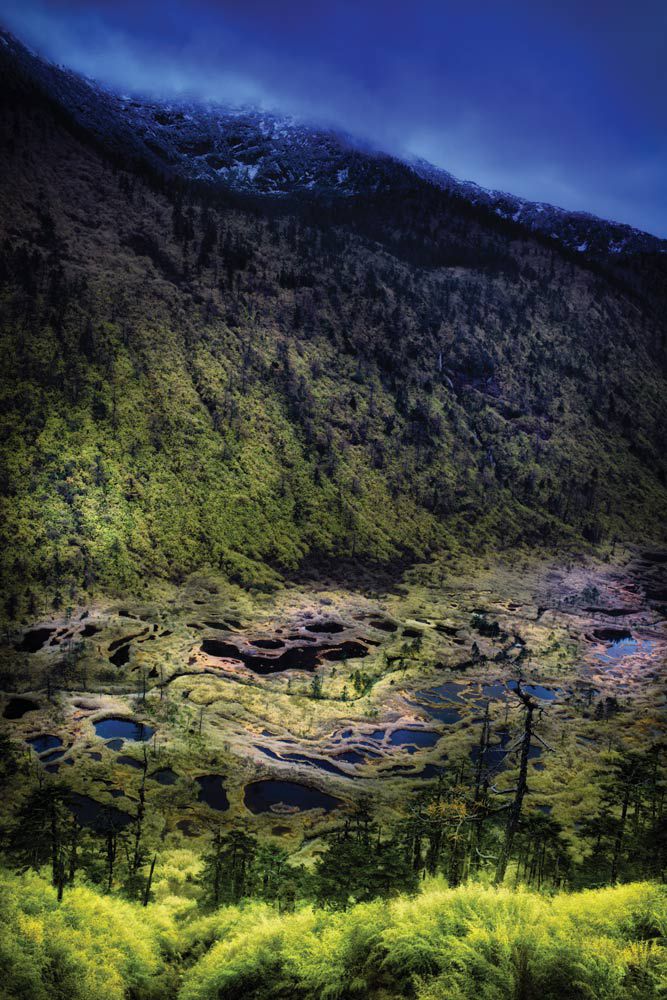

So far, the Gaoligongshan sanctuary only holds the status of a national nature reserve. But its enormous biodiversity, along with Li’s newly discovered species of gibbon, could help turn it into a national park. We roam the romantic forest for two days, but the gibbons here also remain invisible. Eventually we return to Baihua village, disappointed.

The next day, breakfast ends abruptly. “We have found them!” exclaims one of the rangers. We rush to the car, drive a short distance uphill, and hit the bush. In the shadow of a giant ginger plant, Jiang Zi’an is waiting for us. He points out four shapes high up in the treetops. The mother has a baby attached to her chest, while the second infant and its father are moving through the crowns at a leisurely pace. They feast on tender leaves as if every single one is a delicacy, and ignore us entirely. Now, we are lucky indeed.

The landscape of the nature reserve is stunning at dusk (VCG)

The apes scramble through the branches as if gravity does not affect them. We forget the time completely. Jiang returns to the station to grab something to eat. Gamekeepers like Jiang are the true heroes of these mountains: They defy the downpours of monsoon in summer, and hold out in the clammy cabinets of their staging posts during winter. They risk getting stuck in the swamps, or spiked by the bamboo stalks that point up like spears in the brushwood. And all the while, they jealously guard a small pack of apes for paltry pay.

Less than 200 Skywalkers roam the Gaoligong woods. The giant panda, the most high-profile of endangered Chinese wildlife, has a population at least 10 times that. Three-quarters of all ape species in Asia are threatened with extinction, and 95 percent of their habitat is dwindling away. A planet of the ape-less? A March survey by the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences concluded that humanity has “one last opportunity” to save “our closest living biological relatives”.

Jiang returns to take our place. At our farewell, I thank him for his commitment. “That’s OK,” he jokes, “Teacher Li has promised me an extra portion of zhou,” referring to the thick rice porridge that is very popular in the south. Other rangers may ask for extra pay when they have to work overtime; Jiang just regards it as his duty to keep an eye on the animals. I want to express my esteem, but whatever comes to mind seems either pompous or trivial. Whether I am authorized or not, I thank him on behalf of all mankind. He just shrugs his shoulders and goes to follow his protégés deeper into the forest.

Close Encounters with the Third Kind is a story from our issue, “Cloud Country.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.