Demand for sperm banks is rising, but young men struggle to meet tough technical and societal standards to donate

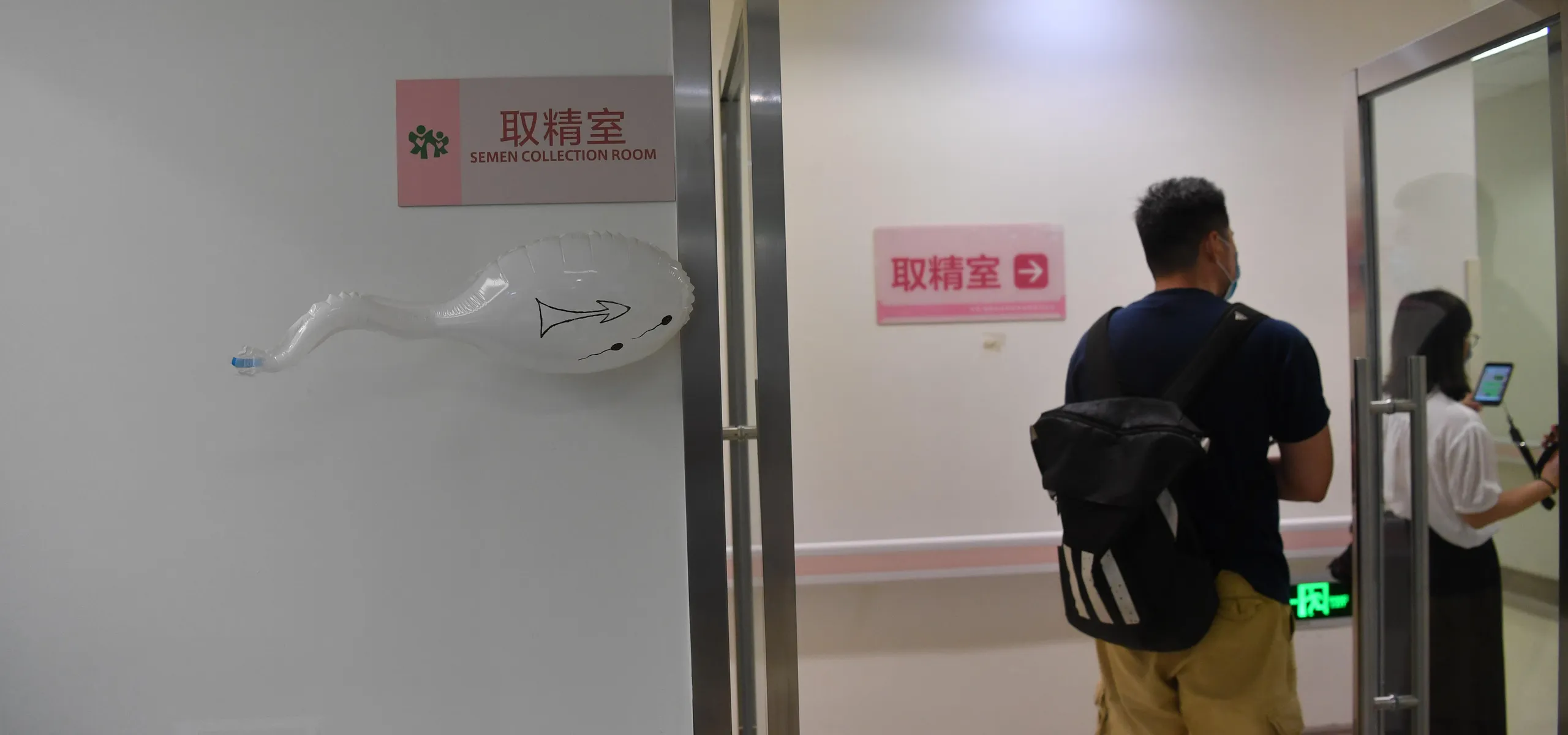

In February 2022, with lingering embarrassment induced by a doctor feeling him up for a testicular exam, Gao Hua entered a poky room in Shanghai Renji Sperm Bank with a wall decorated with faded portraits of women in bikinis or lingerie, early 2000s style. He sat on the small bed and flipped through the channels on the TV, but there was nothing available. “I was expecting to see a porn film,” he tells TWOC.

When Gao, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym, stepped out of the sperm bank 20 minutes later, he was a little disappointed. He had only a medical certificate and a consolation prize of 50 yuan in hand, far from the 7,500 yuan, as Renji had advertised for successful donors, that he had hoped for. His sperm had failed to meet the donation standards.

Reproduction issues have captured public attention in China recently as the country’s population shrinks for the first time in over 60 years. With the number of births falling below 10 million in 2022, a first since 1950, several cities are trying to boost birth rates by giving out cash to new parents, scrapping limits on the number of births, and including assisted reproductive technology in health care coverage. Meanwhile, China’s infertility rate is on the rise: from 12 percent in 2007 to 18 percent in 2020, according to a 2021 report on China’s national reproductive health led by Qiao Jie, a doctor and biologist at Peking University Third Hospital.

The 27 human sperm banks in China are therefore in hot demand from would-be parents. Guangdong Human Sperm Bank, the only one in the province, seems to be more or less self-sufficient with the 10,000 samples it collects from 400 volunteers each year, which covers the needs of the more than 1,000 families who apply to use donated sperm. However, many other facilities around the country have waiting lists of one to two years to access donated sperm, wrote the sperm banks in Hainan and Jiangxi provinces in a plea for donations published on their WeChat accounts this February. Many young men are answering the call to donate, but factors like the strict standards and sometimes social stigma have kept most of them, like Gao, away from the finish line.

In 1981, Lu Guangxiu, a professor at what is now Central South University, established the first sperm bank in China in Changsha, Hunan province, under the request of a patient who had failed to get his wife pregnant. Following two decades of strong unregulated growth of the assisted reproduction industry, in 2001, China’s Ministry of Health came out with regulations on sperm banks and assisted reproduction, forbidding the commercialization of sperm banks and limiting the number of facilities in each province, as well as stipulating that only five women can get pregnant from one donor’s sperm samples.

This year, sperm banks in provinces such as Yunnan, Shaanxi, and Shandong have put out a wave of public calls for donors, many even turning to Weibo for recruitment. The volunteer benefits are attractive: Typically, those who complete multiple donations over a six-month period will receive cash after each donation, which can sometimes accumulate up to more than 7,000 yuan depending on the place.

“Sperm donation is a noble, public service volunteer activity that can elevate personal values, save families, and even help a nation prosper and society harmonize,” writes the sperm bank affiliated with Peking University Third Hospital in an initiative on its public WeChat account.