How a low-ranking Han dynasty courtier came to be known as the founder of the Silk Road

One of China’s most ancient historical figures is now in the spotlight after thousands of years. Zhang Qian (张骞), a Chinese diplomat from the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), is regularly name-dropped as the “founder of the Silk Road,” with President Xi Jinping calling him a “friendly emissary” on a “mission of peace” at the 2017 Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. It is thanks to Zhang, Chinese sources say, that an “open, inclusive and mutually beneficial modern Silk Road” is being built by Chinese trade initiatives.

How did a minor Han dynasty historical figure reach this position of public and international prominence? Though Zhang is presented as an ancient figure of trade and peace, his real story is much more complicated. Following the myth of Zhang Qian through history reveals a complex web of Chinese folk culture, religious movements, European influence, and PRC diplomacy.

Zhang Qian originally appeared in the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), a history of ancient China completed by historian Sima Qian sometime around 94 BCE. At this time in Chinese history, the Han dynasty was locked in a struggle with the Xiongnu, a powerful confederation of northwestern nomads. The militarily superior Xiongnu were a constant drain on the Han military and court treasuries. Finally, Emperor Wu of Han decided to handle the problem by forming an alliance with other tribes or kingdoms in the “western regions,” modern-day Xinjiang and Central Asia.

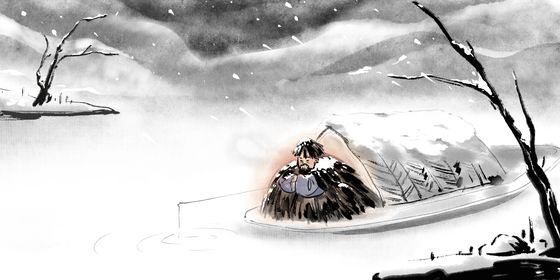

In 138 BCE, the emperor dispatched a low-ranking courtier named Zhang Qian into these unknown lands to seek a military alliance. This marks the first recorded official contact between a Chinese dynasty and the western regions. But unfortunately for the emperor’s military aspirations, Zhang did not complete his mission. He was captured twice by the Xiongnu and, after escaping them, discovered the western kingdoms weren’t interested in allying with the Han after all.

Yet the historical record remembers his journey differently. Zhang redeemed himself to the emperor by providing intelligence on the peoples of the western regions: their kingdoms, geographies, and economies. This intelligence led Emperor Wu to mount a direct campaign against the Xiongnu, eventually extending Han power into modern-day Gansu province. Zhang was remembered in the Records as a key part of the Han’s diplomacy and military strategy.

In later dynasties, Zhang’s famous journey west began to take on a life of its own in the Chinese cultural imagination. The Mogao Caves in the northwestern city of Dunhuang, one of ancient China's frontiers on the western regions, contain a mural of Zhang dating back to the early Tang dynasty (618 – 907). The wall of Cave 323 depicts Zhang, Emperor Wu, and the Xiongnu exchanging and worshiping Buddha statues. The myth that Zhang helped introduce Buddhism to China from the west was popular in this period, showing that his story was already being used to explain all sorts of exchange between China and the western lands.