More educated, autonomous, and aware of their rights than the previous generation, China’s newest migrant workers are ditching factory work for the digital economy

This is the second part of our series on the future of migrant work in China. Read Part 1 here.

Xiao Ying is only 23 years old and already belongs to a dying breed. “A girl born in the 2000s working in a garment factory, do other people my age find this embarrassing?” the Jiangxi province native asks in the title of one of her vlogs on the Chinese video platform Bilibili.

The question might seem absurd to the millions of migrant workers who have filled China’s factory assembly lines since the 1980s, leaving their hometowns in search of work and opportunity in urban areas and manufacturing hubs. But Xiao Ying’s generation, known in China as linglinghou (零零后) or “the post-00s”—more educated, independent, and ambitious than their parents—are different, and fewer and fewer of them are drawn to factory work now.

The regimented work of the assembly line is partly to blame. As Xiao Ying, who dropped out of middle school at 14, explains in her videos, every day at the factory is the same. She gets up shortly before 8 a.m. in her dorm room in central Jiangxi’s Ganzhou city. The sides of her bed frame are covered with thick blankets to create the tiniest of private spaces and shield her from the view of her coworkers who occupy other beds like this in the same room. It only takes Xiao Ying a few minutes to get to work across the street in the garment factory where she will sit at her workstation and repeat the same motion hundreds of times over the course of the next 12 hours.

By 9.30 p.m. when her workday ends, she will have sewn sleeves onto hundreds of shirts before passing them along the assembly line. Eventually, the shirts will be sold for 129 yuan on e-commerce platform Taobao. To earn that amount of money, Xiao Ying has to process about 280 shirts, earning less than half a yuan per piece. “My life is the same every single day, the sewing machine never stops,” she says in one of her vlogs.

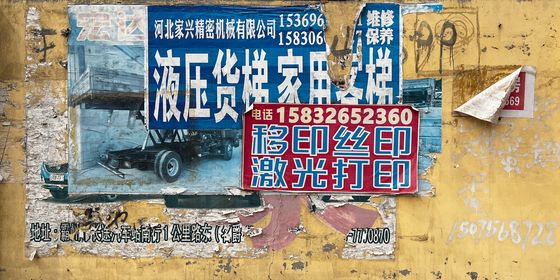

China now has nearly 4.6 million migrant workers born after 2000, according to a 2020 report by the National Bureau of Statistics. Instead of Xiao Ying’s humdrum routine, many prefer working in the digital platform economy and other new gig-based opportunities for the promise of more autonomy and flexibility. According to domestic media, some factories in south China’s Pearl River Delta, the powerhouse of light manufacturing, are even reported to be struggling to staff assembly lines. Where once young people lined up out the door to apply to assemble clothing and electronics, bosses now go out on the street holding recruitment placards promising flexible hours and tasty meals.

Why China’s Gen Z Migrant Workers Are Leaving the Assembly Line is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.