With a growing urban-rural gap and lack of social security, China’s first-generation migrant workers are heading back to the workplace

To fool recruiters at Beijing’s Liuliqiao day labor market, 60-year-old Zhao Hua has dyed her gray hair black. On a Tuesday morning in March, Zhao has arrived, as she has every day in the last month, hoping to get a temporary gig on a construction site, event crew, or any other odd job opportunity despite being well past legal retirement age.

When TWOC meets Zhao shortly after 1 p.m., though, she has just been denied an elevator operator job by a recruiter who was diligent enough to check her age, despite the hair dye. “They told me they didn’t want anyone over 50, let alone 60,” she complains. She has been forced to try her luck at Liuliqiao because the regular jobs she used to hold, such as cleaning, also won’t hire seniors like her. “It’s not like I’m not competent enough to do the [elevator] job. I can climb stairs [like they asked for], but they just don’t want anyone over 55.”

“I’ve still got it in me, so why won’t they give me anything?” she asks.

Zhao, who agreed to be interviewed by TWOC under a pseudonym, is part of China’s first generation of migrant workers. In the 1980s, they left their rural hometowns to work on assembly lines, construction sites, and behind the service counters of China’s more economically developed coastal cities after the reforms. They have now reached retirement age: 60 for men, 55 for white-collar women, and 50 for blue-collar women like Zhao.

Yet many are still in limbo, left outside the urban pension system and still burdened by expenses like medical bills or their children’s education, marriage, or housing costs. Rather than enjoying their twilight years at home, some are finding themselves back on the labor market and forced to take temporary jobs, often uncontracted and uninsured, in the short-term labor market, with few prospects of stopping—until death.

Zhao was in her 20s when she first left her hometown of Fuyang in central China’s Anhui province to find work in the nation’s capital, first working as a nanny before changing to menial tasks that offered more flexible hours, like carrying bricks at construction sites, plastering walls, and unloading goods.

At the start of the pandemic, Zhao returned to Fuyang due to a lack of work opportunities in the city, but has returned to Beijing at age 60 in order to find temporary work and reduce the financial burden on her 33-year-old son, who is farming at home and raising his five school-aged children. But so far, she has only earned 200 yuan from one day of plastering for the entire month of March, and was rejected for every other job due to her age.

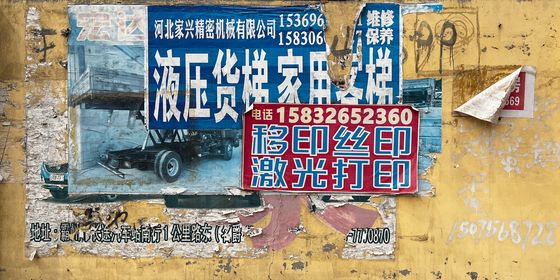

When TWOC finds Zhao, she is sitting among a dozen men in their 50s or older, who are sitting on cloth sacks packed with their belongings and holding cardboard signs advertising their services on a street near Liuliqiao in Beijing’s Fengtai district. This ad hoc labor market outside the Third Ring Road has become a junction for migrants living on a budget in Beijing’s outskirts, who may need to get up at 5 a.m. and spend two hours traveling to this street corner, where they spend the day waiting for recruiters offering temporary jobs such as loading parcels and laying cement.

More often, though, they end up waiting for up to 10 hours and getting no work, chatting and playing cards to kill time before going home and trying again the next day.

The Aging Migrant Workers Who Can’t Afford to Retire is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.