A character to rest against

One morning circa 1046 BCE, the poet Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修) was struck by the sight of people from different walks of life taking different routes up the mist-shrouded Mount Chushan (滁山) in modern-day Anhui province. He immortalized his feelings in the essay, “Account from the Old Drunkard’s Pavilion (《醉翁亭记》)”: “Those carrying burdens sing along the road, while those walking rest under trees (至于负者歌于途,行者休于树 Zhìyú fùzhě gē yú tú, xíngzhě xiū yú shù).”

In both the ancient world and the modern day, much has been written on the importance of rest. Poet Lu You (陆游), who lived in the 12th and 13th centuries, wrote after a long evening of studying by the lamp, “What do I accomplish from working hard? It is better to have used the time to rest (默默何所为?且复自休息 Mòmò hé suǒ wéi? Qiě fù zì xiūxī).” Likewise, Bai Juyi (白居易), a renowned poet of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), wrote, “It is common to see people who are busy suffer from disease, while rare to see healthy people willing to rest (多见忙时已衰病, 少闻健日肯休闲 Duō jiàn mángshí yǐ shuāibìng, shǎo wén jiànrì kěn xiūxián).”

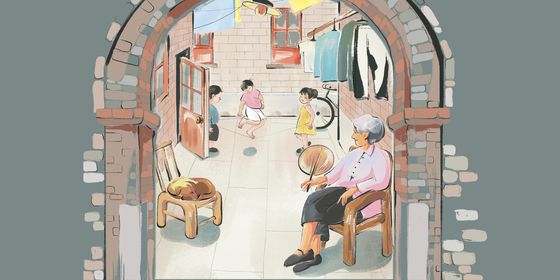

The Chinese character for rest is 休 (xiū). It takes a form which is both simple and self-explanatory: on the left is 亻, the “person,” and on the right is a tree, “木.” Combined, they create a pictorial character resembling a person leaning against a tree. The character has become simplified by retaining its general form from the Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE) to the present.

The earliest meaning of the character is “to rest” or “to halt,” as indicated by the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) linguist Xu Shen (许慎) in the Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》): “休 is the action of rest and stopping (休,息止也 Xiū,xī zhǐ yě).” This meaning persists today, commonly found in terms like 休息 (xiūxi, to take a break) and 休业 (xiūyè, to suspend business).

Breaks are a chance to recharge and regain energy. Thus, 休 later took on the connotation of recovery. For instance, a ceasefire is 休战 (xiūzhàn), and temporary absence from school due to illness or personal reasons is 休学 (xiūxué).

But some breaks are permanent. In the patriarchal world of feudal China, men (and only men) were allowed to end a marriage, divorcing their wife (休妻 xiūqī) using a document called 休书 (xiūshū) if she violated one of seven moral codes, such as by committing adultery and failing to bear children. Divorced women, called 弃妇 (qìfù, discarded wives), faced being insulted by their neighbors and indifference from their family members, and some even committed suicide to redeem their honor.

Today’s overburdened employees often fantasize about the time they can stop working and enjoy 退休 (tuìxiū, retirement). For ancient Chinese literati though, 休 often evoked sorrow, as many were forced into retirement by political exile or the machinations of rivals at court. Du Fu (杜甫), a poet and politician of the Tang dynasty, was full of bitterness in his twilight years after being expelled from the Tang court at Chang’an. He shared his opinion of retirement in a poem that goes, “名岂文章著,官因老病休 (Míng qǐ wénzhāng zhù,guān yīn lǎobìng xiū, I made a name for myself with my poems and articles, but now I have to retire due to my illness and old age)?”

The character 休 also implies “prevention.” For instance, one might warn a rude person in an old-fashioned way, “Do not be impolite (休得无礼 Xiūdé wúlǐ).” A person who makes an unrealistic or insulting proposal to someone else might find themselves rejected with the phrase “Don’t even think about it (休想 xiūxiǎng)!”

A person who rests under a tree is also seeking shelter under its thick foliage. Therefore, 休 has also taken on the connotation of “protection.” Archeologists have found bronzeware dating back to the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 – 771 BCE) engraved with the idiom 对扬王休 (duìyáng wángxiū, gratitude for the protection of the king), signaling the bond between a sovereign and his vassal.

Being taken under the wing of a protector is a blessing, so 休 has also been extended to mean auspiciousness and felicity. As beings sharing this planet and bonded by a common destiny, all humanity 休戚与共 (xiūqī-yǔgòng, shares prosperity as well as woe).

Illustration by Wang Siqi

On the Character: 休 is a story from our issue, “Something Old Something New.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.