When the Harlem Renaissance briefly flourished in Shanghai

Amid the swirl of people, carts, and humidity on Shanghai’s Bund, American poet Langston Hughes scanned the streets for a free rickshaw. But no sooner had he secured a ride than he stood up in his seat and yelled out at a passing vehicle, “Hey, man!”

“What ya sayin’?” the passenger in the other rickshaw shouted back. Across the world from his home in New York City, Hughes had recognized a fellow African American, and more precisely, another resident of the neighborhood of Harlem making their way through one of Asia’s most exciting and vibrant cities on this sweltering July day in 1933.

In the 1930s, Shanghai was the fifth largest city in the world. Thousands of Jews fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe and Russians escaping the Soviet Union arrived by boat and train, often without passports or much money. Thousands more Chinese came escaping the poverty and instability of a country suffering from the global economic depression and the encroaching Japanese imperial armies.

By the time Hughes arrived in Shanghai, the city was divided into zones controlled by different governments, warlords, and foreign powers including the Japanese, British, and French. In this political no-man’s land, Shanghai became a crossroads where people from all continents met on the banks of the Huangpu River. Hughes, on his way home after an extended sojourn in the Soviet Union, was one of many intellectuals and artists attracted to the city.

But Shanghai was also a colonial outpost fractured along lines of race and class. The color lines that so appalled Hughes in the US had followed him across the sea to Asia. In his memoir, I Wonder as I Wander, Hughes recalled that none of the leading hotels in the International Settlement accepted Asian or Black guests. Many of the city’s clubs had official—or unofficial—restrictions for non-whites.

“I was constantly amazed in Shanghai,” wrote Hughes, “at the impudence of the white foreigners in drawing a color line against the Chinese in China itself.”

Yet as he explored more of the city, Hughes found the color line didn’t always extend to the Chinese sections of Shanghai. “To tell the truth,” Hughes recalled, “I was more afraid of going into the world famous Cathay Hotel than I was of going into any public place in the Chinese quarters…beyond the gates of the International Settlement, color was no barrier. I could go anywhere.”

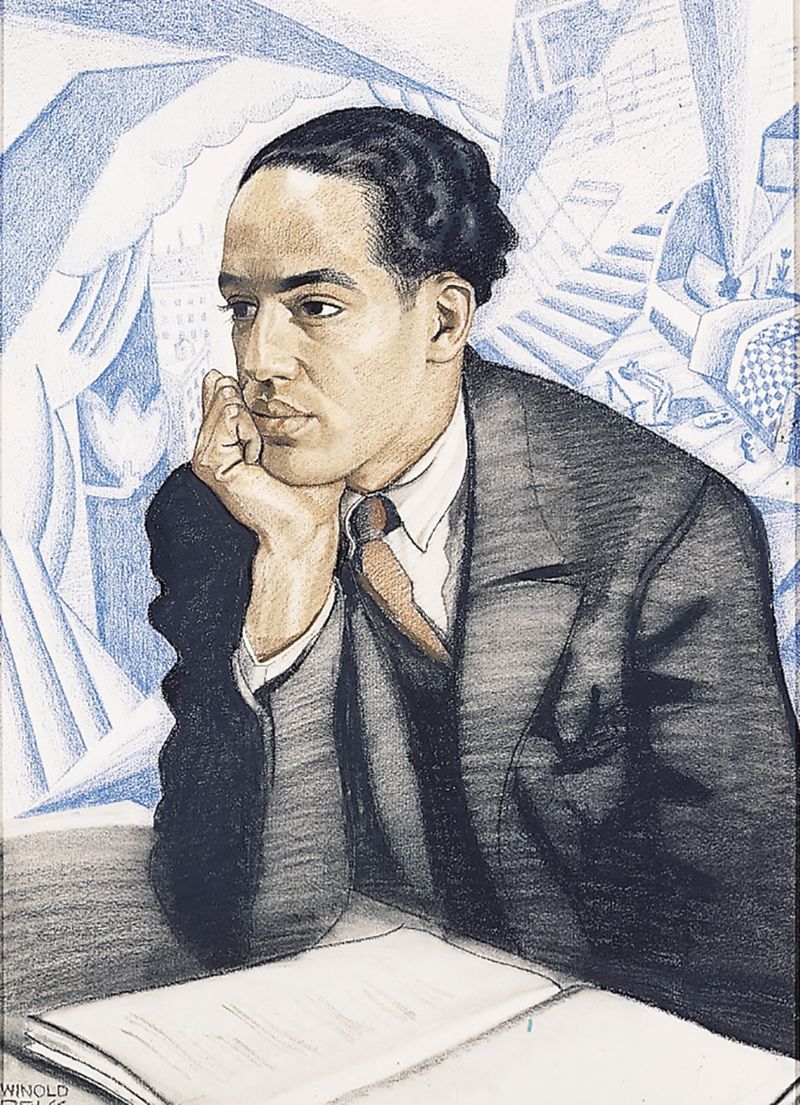

Hughes later maintained a residence in Harlem, but wandered the world as a young writer

Hughes was one of the most celebrated literary figures of the Harlem Renaissance, a flowering of Black intellectual and artistic culture in American cities beginning in the 1920s. He honored Black life and culture in his poetry and was one of the first African American writers to earn a living from his craft. Hughes traveled around the US and the world reading his poetry, meeting likeminded intellectuals and activists, and seeking inspiration.

In the 1930s, his journeys took him to Haiti and Cuba, and eventually to the USSR and East Asia. Hughes wanted to break into the movies, but opportunities for Black screenwriters were limited in Hollywood at the time. When the chance came to be part of a propaganda film being made in the Soviet Union, Hughes canceled his US speaking engagements and headed for Moscow.

While politically sympathetic and appreciative of the Soviet concern for the plight of African Americans, Hughes found working within the system challenging. The movie they were supposed to make was written by a famous Russian writer and directed by a young German filmmaker, neither of whom had ever been to the US or had ever met a Black person. Filming eventually shut down for political reasons, and Hughes was glad to be finally heading home in the summer of 1933.

It was on his way back to the United States nearly a year later that Hughes visited China, Korea, and Japan. In Shanghai, Hughes had lunch with Soong Ching-ling, the widow of the statesman Sun Yat-sen, who asked Hughes about mutual acquaintances living in Moscow. He also met the renowned author Lu Xun.

At the time, Shanghai was experiencing an intellectual and artistic moment of its own. Shanghai-based historian Andrew Field points to the parallel development of new forms of what it meant to be modern in both Harlem and Shanghai. “You had writers such as Mu Shiying and Liu Na’ou who were writing very linguistically creative stories about modern life in Shanghai,” says Field.

“They were influenced by the global modernist literary movement and by writers such as Paul Morand, as well as by Japanese writers from that period…There were all sorts of parallel trends about exploring the human condition and modern urban life and nightlife through art and literature.”

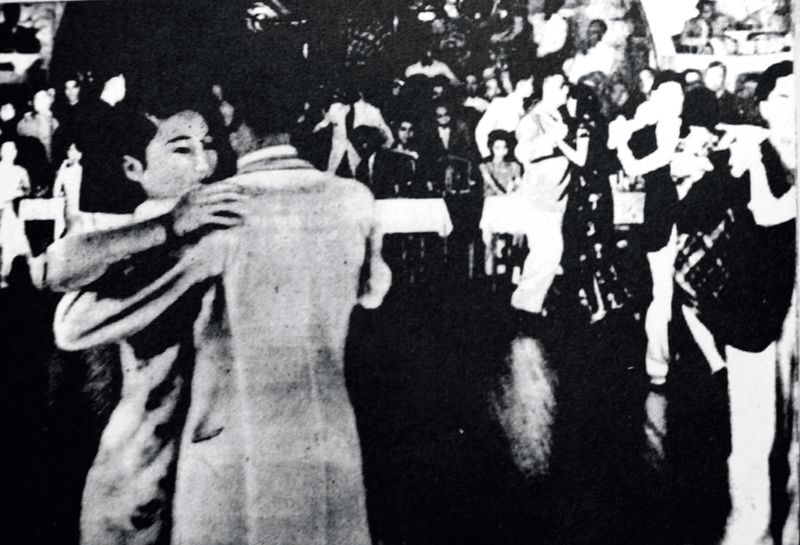

While the literary relationship between Shanghai and Harlem was less direct and thematic, Hughes discovered a more robust connection as he experienced the city’s vibrant nightlife. Shanghai after dark was a polyglot world of cabarets, dance halls, theaters, and nightclubs.

Shanghai was famous for its cosmopolitan nightlife featuring musicians and other performers from around the world

Americans, Russians, Chinese, Brits, Japanese, and a host of other nations’ peoples contributed to the boisterous world of Shanghai’s nighttime entertainment. The city was full of jazz bands and combos who could all play the latest popular numbers from America and Europe, although many of the musicians were from the Philippines. There was a less savory side to Shanghai after dark as well: Prostitution was common, with women, men, and in some cases even children available to satisfy the sexual proclivities of revelers.

One of the more popular bands in Shanghai was Buck Clayton and the Harlem Gentleman. The name of the group was a trick of marketing: Buck was originally from Kansas, and the band had never played in Harlem, but as Field notes, “The name had cachet, and they were all African Americans.”

While in Shanghai, Hughes spent evenings at the Canidrome Ballroom, part of the enormous entertainment complex and greyhound racetrack that was one of Shanghai’s main playgrounds for residents and visitors alike. He listened to American expatriate Teddy Weatherford and his band, who played a regular circuit that took them to ports of call throughout Asia from Mumbai to Manila. Hughes also met the famous singer Nora Holt, who was one of many Black artists performing in Shanghai that summer. Hughes’ friendship with band leader Weatherford nearly caused the poet to miss his departure.

Hughes had a ticket on a Japanese ship sailing for San Francisco via Yokohama. On the morning of his departure, Weatherford surprised Hughes at his hotel, arriving straight after closing time at the Canidrome after being up all night. Before Hughes had even packed or checked out, Weatherford bundled the American writer into his car and drove him out to his house on the edges of the city. There, the musicians and their families cooked up a feast right out of the Soul Food kitchens of the American South: biscuits, gravy, and fried chicken. Hughes enjoyed the hospitality—and the food—but only barely made his boat.

Hughes’ time in China lasted only a few weeks, but in 1938 he published the poem “Roar, China!” in which he condemned the colonial system and the export of American “Jim Crow” regulations abroad. Like many 20th century African American writers and activists, Hughes’ denunciations of racism also contained trenchant critiques of colonialism and capitalism.

Hughes would later distance himself from Soviet-style Communism, but he remained an outspoken and influential voice against racial and social injustice until his death in 1967. In the final stanzas of “Roar, China!” Hughes wrote:

Smash the iron gates of the Concessions!

Smash the pious doors of the missionary houses!

Smash the revolving doors of the Jim Crow YMCAs.

Crush the enemies of land and bread and freedom!

Stand up and roar, China!

You know what you want!

The only way to get it is

To take it!

Roar, China!

The Jazz Age is a story from our issue, “Disaster Warning.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.