How verses by an obscure Tang hermit inspired an American countercultural movement

A thousand years after the death of the cave-dwelling poet Hanshan (寒山) in the Tiantai Mountains of east-central China, American writer Gary Snyder came down from a summer repairing trails in Yosemite, cracked open a volume of the Chinese poet’s verses in the library of UC Berkeley, and found a striking mirror of his own disillusionment with modern society.

“Men ask the way to Cold Mountain,” goes one of Hanshan’s poems. “If your heart was like mine, you’d get it and be right here.” In 1958, two decades before Snyder would win the Pulitzer Prize for his own poetry, he published translations of 24 of the reclusive Tang dynasty poet’s works—casting Hanshan into the American imagination, and leading a ragtag group of American writers stumbling along Hanshan’s path.

Although rarely found in collections of Tang poetry, and considered obscure in today’s China, Hanshan is often introduced to American readers through the works of the Beat writer Jack Kerouac. In Kerouac’s thinly-veiled autobiographical novel Dharma Bums, which he dedicated to Hanshan, the protagonist visits his friend Japhy (who represents the real-life Snyder) in a small Berkeley shack, and learns about the poet: “Han Shan you see was a Chinese scholar who got sick of the big city and the world and took off to hide in the mountains.” The protagonist bends over Japhy’s shoulder and watches him read the “big wild crowtracks” of Chinese characters: “Who can leap the world’s ties and sit with me among white clouds?”

Kerouac and Snyder took up Hanshan’s invitation. Like their counterparts in Dharma Bums, they headed to Desolation Peak in the Sierra Nevada in summer of 1956, shadowed by Snyder’s ongoing effort to translate Hanshan’s verses. Choosing poverty and freedom over the trappings of society, they found spiritual elevation in the mountains. Kerouac writes in Dharma Bums, “I’d rather hop freights around the country and cook my food out of tin cans over wood fires, than be rich and have a home or work.” In Tang China, Hanshan had expressed similar sentiments, “I prefer unpolished jade/ you can have your jewels./ I could never join the flock/ of bobbing ducks on waves.”

Little is known about Hanshan; not even exactly which century he lived in, though most scholars place his life between the 7th and 9th centuries. From his poetry, one deduces that Hanshan was well-educated, and perhaps once worked as a petty bureaucrat. Hanshan lamented, likely of the rigid system of imperial examinations, “I labored in vain reciting the Three Histories/ I wasted my time reading the Five Canons/ I’ve grown old checking yellow scrolls.” Kerouac and his Beat cohorts, too, denigrated American universities as “nothing but grooming schools for the middle-class non-identity which usually finds its perfect expression on the outskirts of campus in rows of well-to-do houses with lawns and television sets in each living room with everybody looking at the same thing at the same time.”

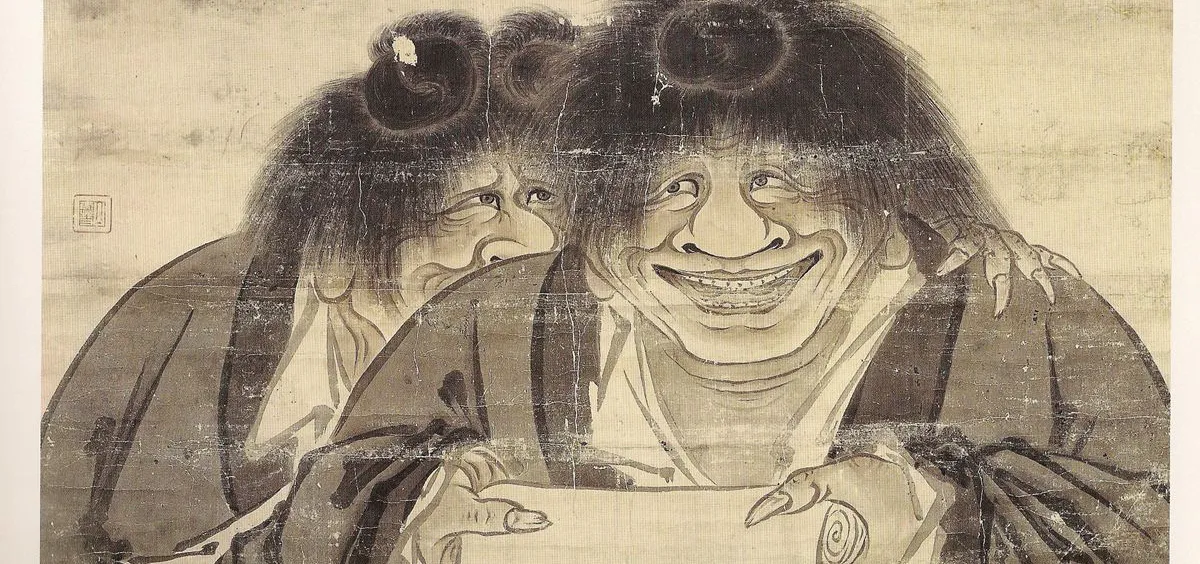

Hanshan is sometimes depicted with a companion, Shide, the kitchen helper Guoqing Temple

Besides acrimony toward the earthly world of “red dust,” Hanshan and Kerouac shared a humble euphoria for life on the mountain. Hanshan wrote with absolute earnestness: “With a vast net of stars, the night is deep/ In my cave, I light a single lamp before the moon sets…hanging in the blue sky, this is my heart.” Alone on his cliff, gathering plants and herbs to boil during the day, and composing poetry by moonlight, Hanshan effused, “Since I escaped to Cold Rock/ I’ve been happy, singing and laughing a long, long time.” Yet in an unexpectedly tender moment, one of Hanshan’s verses expresses longing for someone to share his alpine pursuits: “I discuss the profound principle with the white cloud/ Though the feeling of the wild is in mountains and waters, truly/ I long for a companion of the way.”

Kerouac, too, wished to “go prowling in the wilderness to hear the voice crying in the wilderness, to find the ecstasy of the stars, to find the dark mysterious secret of the origin of faceless wonderless crapulous civilization.” He was “Happy. Just in my swim shorts, barefooted, wild-haired, in the red fire dark, singing, swigging wine, spitting, jumping, running—that’s the way to live.” On his 55th day on Desolation Peak, Kerouac wrote, “I called Han Shan in the mountains: there was no answer. I called Han Shan in the morning fog: silence, it said.” Page after page, Dharma Bums is a novel-length response to Hanshan’s life, a modern American’s search for Cold Mountain’s shadow in the snowy Sierra, and other cliffs and caves in the heart.

The efforts of Snyder, Kerouac, and other early Hanshan translators roused a chorus of response from an entire generation of American admirers. In 1974 in Greenfield, Massachussetts, a bookshop owner placed Burton Watson’s 1962 translation of 100 Hanshan poems into the hands of James Lenfestey. The young poet “fell in love with that voice, like that of an older brother,” he recounts in Seeking the Cave: A Pilgrimage to Cold Mountain, published in 2016.

Lenfestey began writing poems in response to his so-called “mysterious poet friend.” A poem by Hanshan reads, “Here we languish, a bunch of poor scholars…our only joy is poetry…We could inscribe our poems on biscuits/ And the homeless dogs wouldn’t deign to nibble.” Lenfestey responds, tongue firmly in cheek: “I languish in a car with battered friends…young people won’t listen to us, and old ones mock our shaggy hair/ In despair, we read Hanshan’s poems as we drive…we devour these thousand-year-old biscuits/ like homeless dogs!”

The same year, 1974, Hanshan’s verses found their way into the hands of Bill Porter, an American graduate- school dropout living in a monastery in Taiwan. By the time he left the monastery, Porter had translated nearly 100 of Hanshan’s poems, and, after moving into a converted farm shed near a lake, completed 150. Porter would eventually present a translation of 300 of Hanshan’s poems in The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain, published in 1983 under a pen name he borrowed from a Daoist legend, Red Pine.

For the past half century, Hanshan has been a patron saint of anti-materialism among freewheeling American literati. Early translations cast Hanshan as a stoic and unflappable recluse. As his entire corpus of 312 surviving poems (out of 600 he claimed to have written) were finally translated and published in English by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Peter Levitt in 2018, a fuller portrait of the poet has emerged. “He was a flesh-and-blood sage, not a bronze or porcelain image,” wrote John Blofield in the introduction to Bill Porter’s Collected Songs.

Hanshan was not without his private sufferings, and some of his verses are openly vulnerable, even confessional. One night, he wrote that he dreamt that he saw his wife cast in moonlight at the loom, but she did not recognize him with his white hair. Observing the passage of years, he wrote, “Who would guess that under my wisteria hat/ there is a sadness this old?” In his 60s, after 30 years on Cold Mountain, Hanshan recounted visiting close friends whose “lives burned out like candles/ they drifted off like water in a stream./ This morning I faced my solitary shadow—before I knew it, two threads of tears came streaming down.”

Moved by the luminosity of Hanshan’s poetry, scholars have searched for clues to his real identity. All based on sparse evidence, some conjectured Hanshan may have been a pen name of the official Lu Qiuyin; Porter suggests Hanshan was a nobleman who fled the capital to evade punishment for involvement in the An Lushan Rebellion; Tanahashi and Levitt propose there was not one but three Hanshans, writing in successive centuries, based on “linguistic analysis” of inconsistent rhyme schemes and use of historical terms (Porter disagreed, retorting that Hanshan may have simply spoken a regional dialect). There is even bickering as to how the poet died—a Tang official wrote that he hopped, laughing gleefully, into the crack of a rock that closed behind him.

Corpse aside, the corpus thrives; the poet is shrouded in mystery even as his myth climbs into the crevices of readers’ hearts. In 2017, Christopher Nugent wrote in The Poetry of Hanshan, Shide and Fenggan, “Western readers of Hanshan…put the emphasis on his identity as a charismatic dissident. Snyder’s championing of the poems resulted in Hanshan becoming a sort of countercultural hero, whose personality was an essential part of his appeal.” Living his values in the midst of an intricately hypocritical world, Hanshan represented a purity of lifestyle that many yearned for but would never achieve, whether in Tang China or 1950s America.

Like a Shakespearean madman whose stark ravings contain the most lucid, burning truths, the wild-eyed Hanshan became the prophet in rags that Americans yearned for, and resurrected in their time of deep spiritual thirst. Porter muses in his travel memoir Finding them Gone, “There was something about [Hanshan’s] craziness that impressed others, something that wasn’t crazy at all, which made people see the craziness going on in their own lives and in their own times.” In Hanshan’s own words:

When men see Han-shan,

They all say he’s crazy

And not much to look at –

Dressed in rags and hides,

They don’t get what I say

If I don’t talk their language,

All I can say to those I meet:

“Try and make it to Cold Mountain.”

Translations of Hanshan from:

Cold Mountain Poems, translated by Gary Snyder, Counterpoint Press, 2013 edition.

Cold Mountain: 100 Poems by the Tang Poet Han-Shan, translated by Burton Watson, Columbia University Press, 1970.

The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain, translated by Red Pine, Copper Canyon Press, 1983.

The Complete Cold Mountain, translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Pever Levitt, Shambala Press, 2018.

Poet’s Peak is a story from our issue, “Tuning Up.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.