On the 650th year of this famous dynasty’s founding, a leading historian examines why its legacy endures

This year marks the 651th anniversary of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), founded in 1368 by Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), a monk turned rebel general turned paranoid doomfreak tyrant, and the first commoner in almost 1,500 years to be crowned emperor.

As the Hongwu Emperor, the Ming progenitor’s leadership style made Lord Voldemort look like a member of the Human Potential Movement; but Zhu got the job done. His descendants, however, were a decidedly mixed lot. Despite its uneven roster of rulers, the Ming era saw considerable achievements in the arts, letters, and philosophy. It was also a time of economic and commercial development which, in turn, created new challenges between the state and society.

Michael Szonyi is Professor of Chinese History and Director of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University, and a social historian of late imperial and modern China. His most recent book, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China, published last year by Princeton University Press, looks at how ordinary people interacted with the state during the Ming era through the ways in which families fulfilled their obligation to provide soldiers for the army. TWOC spoke to Dr. Szonyi about all matters Ming, and what those in the modern era can learn from this history.

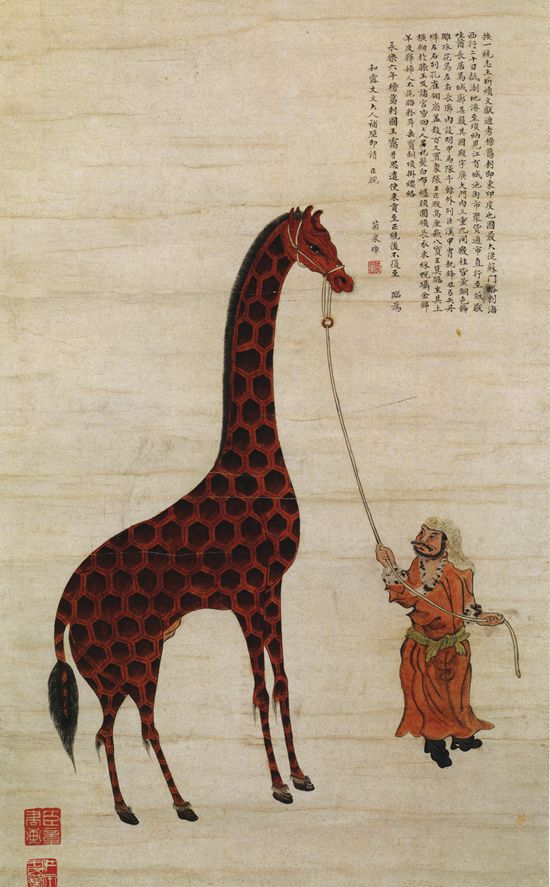

“Tribute of a Giraffe from Bengala,” a Ming dynasty painting later copied during the Qing (VCG)

The Ming dynasty is 650 years old this year, but why should we care? What’s so special about the era?

One reason the Ming matters is that Chinese people think the Ming matters. Today, [they] continue to consume [Ming] history voraciously—in books, movies, and TV serials. One of the bestselling works of history in the last decade is a series of stories about the Ming, Those Happenings of the Ming Dynasty (《明朝那些事儿》a book series penned by Shi Yue), which spawned a host of imitators. I speculate that one of the reasons the Ming is fascinating to Chinese people today is that they perceive parallels with their own time. The Ming also matters today because it is being used to make claims about the present and future.

One of the most celebrated episodes in Ming history was the Zheng He (郑和) voyages. Zheng He has taken on new significance in recent years in light of the Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese leaders cite Admiral Zheng as evidence that Chinese expansionism should not be seen as threatening. If they knew the real history of the voyages, the leadership would not be talking so much about him. Most scholars today see Zheng as commander of a massive military mission, intended to awe other states into submission: He routinely interfered in local domestic affairs, and conducted military action where it suited him—not really the image you want people to think of when they consider a growing Chinese presence in their region.

Moving from popular history and historiography to history itself, I think the Ming is significant as having been one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, with the largest standing army in the world (after the collapse of the Mongols), and a highly sophisticated political apparatus that sought to register and monitor its entire population in ways that look very familiar to us, but without the technological tools that modern states have at their disposal. In the 16th century, China was at the heart of the global economy—it produced the high-tech goods that people throughout Eurasia wanted to have. At the time, China probably accounted for about a third of global GDP—just about the share that China should have later this century.

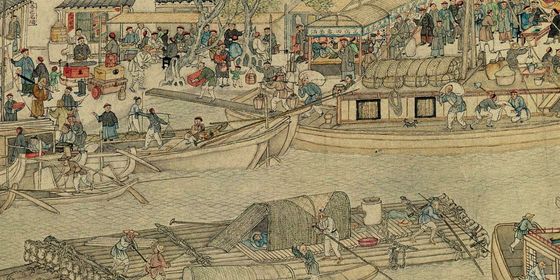

Picture of merchant from the Ryukyu Kingdom arriving in Fuzhou harbor in 1372 (VCG)

In the past few years, overseas scholars have gotten dragged into a “tempest in a Qianlong-era teacup” with some members of Chinese academia, particularly over issues related to ethnicity, frontier studies, and other subjects, all very loosely cobbled under the heading of “New Qing Studies.” What’s the relationship like among foreign and domestic Ming scholars?

My sense is none of the scholars in the New Qing school set out to be deliberately provocative. But their discoveries in the archives, and using Manchu sources, led them to conclusions that turned out to undermine conventional wisdom and to have significant implications for contemporary China. While I am sometimes jealous of the attention these scholars get in the popular media, I’m certainly glad not to bear the brunt of scurrilous attacks in the state media.

There are big debates in Ming history, but they tend to be more academic and less heated. For example, there was clearly a big economic downturn in the 14th century in China. Was it caused by the disruption of the Mongols and their Yuan dynasty, or by the autarkic policies of the early Ming? Chinese nationalists would like it to be the former, but there’s a lot of evidence it was the latter. Some scholars see in the public debates of the late Ming the emergence of a proto-civil society; their opponents think this is wishful thinking. In a sense, this is a debate about whether the late Ming can be described as liberal.

Another big debate is about demography. We used to think that there was a population explosion in the early-to-mid-Qing, and this was a big factor in the domestic turmoil of the 19th century. Some demographic historians now believe that late Ming population data was systematically under-reported. This would suggest that the demographic increase began under the Ming and was therefore much slower in coming. If you accept this, then it calls into question the conventional wisdom about Qing decline.

One of your students comes to you and says: “I want to be a scholar of the Ming era! Point me toward the cutting edge of research currently being done in Ming studies.” What would you tell them?

Well, I hope it won’t come across as immodest, but the first thing to read would be my new book, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China. What I am proudest of in the book is that I am able to show how ordinary people in Ming times were able to devise amazingly complex and sophisticated strategies to deal with their obligations to the Ming state.

Two other wonderful historians I recommend reading are Sarah Schneewind and David Robinson. Both also have forthcoming books. Sarah’s is a study of living shrines—shrines to worship men who were still living. She uses this subject to explore the idea of political participation in Ming; supporting and worshiping at these shrines, she argues, was a way people could make their political views known.

David sets the Ming in the larger Eurasian context, exploring its relations with the Mongols, Korea, and other states. He shows how Ming foreign policy may have been largely isolationist, but this did not mean the Ming was isolated.

Ming Matters is a story from our issue, “Modern Family.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.