Is this the end of Chinese fantasy fiction or a reluctant new beginning?

In the wake of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy and the Harry Potter series, China saw the ascension of new deities: the “Seven Gods.” These gods—lacking in most divine aspects—were bespectacled young men in their 20s who created the bedrock for an entire genre of Chinese literature.

The idea first took root in 2002, when a user with the I.D. “Dajiao” suggested incorporating “Eastern” features in a Western-style fantasy realm. The result was Novoland, or “Jiuzhou” (九州, nine regions): a unique, crowdsourced universe that would provide a generation of writers with a shared setting for fantastic tales that would shape Chinese fantasy into a full-blow literary genre. It would later be revealed that the man behind that “Dajiao” web handle was none other than Pan Haitian—today one of China’s most beloved fantasy and sci-fi authors.

The seven main writers and active forum members became the “Seven Gods” forming a committee to oversee the creation of this new world. “There are countless heroes, dynasties, and millions of stories. It needed to be a product of cooperation,” Pan tells TWOC.

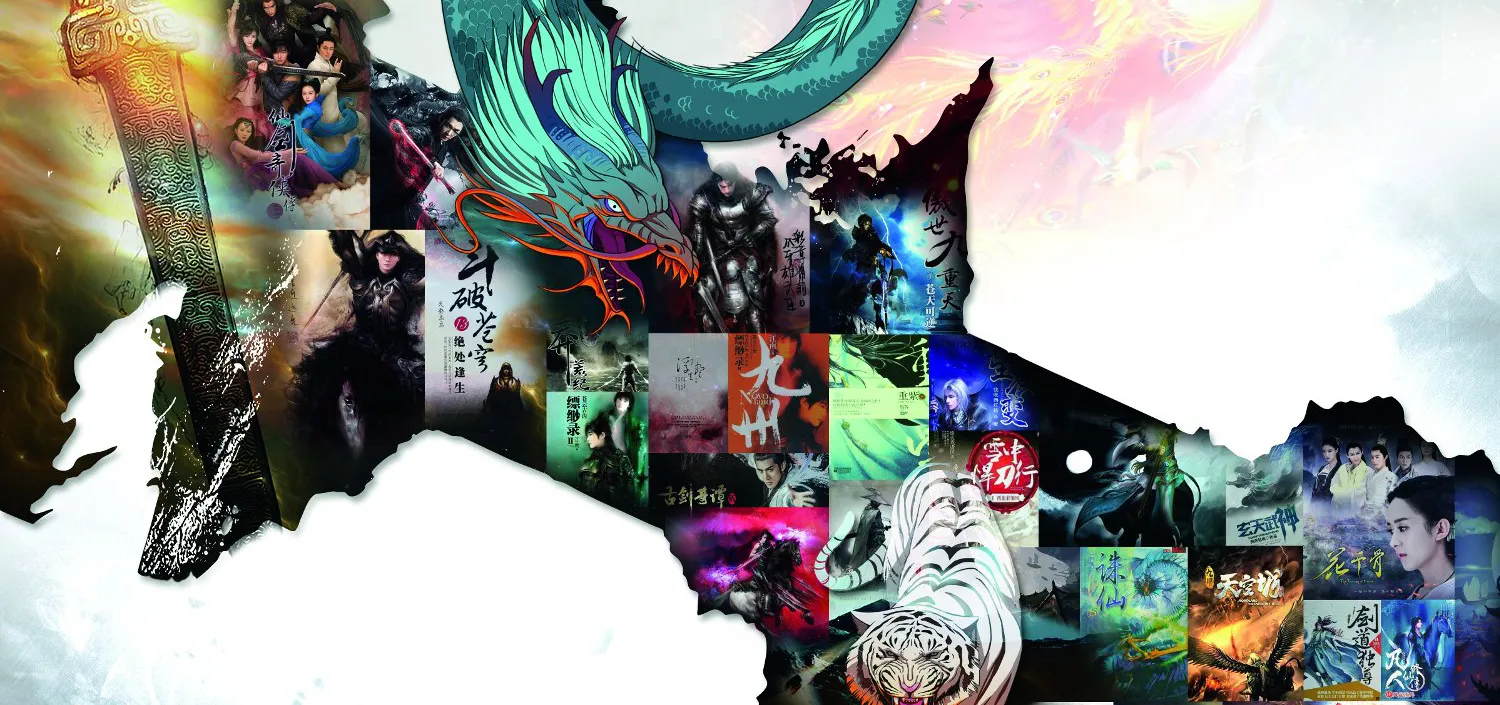

Having materialized into over 40 full-length novels and stories across 100 magazine issues and anthologies in the last 15 years, to say nothing of works released online, Novoland is potentially the most productive fictional universe of all time.

The Chinese fantasy universe began with a fight between the two gods of order and chaos; both perished in the battle but their spirits continue to influence events. The main conflict in Novoland is between a group of Jedi-like warriors who promote order and peace and a group of warlocks that introduce war and chaos.

Caught up in the narrative are the humans, the largest race, as well as a winged tribe gifted at archery, roughly the equivalent of elves (but with super-navigation skills). Also in this world are the Kua Fu, giants inspired by prehistoric Chinese myths living in the cold North; He Luo, dwarfs skilled in various crafts; and Jiao Ren, the mermen who emerge from the sea to trade with people on land, all consistent with Chinese folklore. Finally, there are the Mei, who are purely aetherial beings that can form a tangible form by spiritual cultivation. The inspiration from Chinese history is palpable, the name “Jiuzhou” originally referring to the nine territorial divisions of ancient China.

Despite having been influenced by Western fantasy, Chinese fantasy literature is distinct in both style and substance. “The theme of Western fantasy seems to be how the bright side of humanity overcomes its dark side; man and god become one. In this sense, fantasy can be translated to mohuan (魔幻, roughly, sorcery-fantasy),” observes Professor Zheng Baochun at Central China Normal University, who is also a wuxia fantasy writer under the penname Shu Feilian. “Chinese fantasy emphasizes the cultivation of the soul and flesh, as well as enlightenment through practice. So it’s called xuanhuan (玄幻, mystery-fantasy).”

In fact, there’s an entire subgenre of Chinese fantasy called xiuxian (修仙), which means “cultivating immortality,” or cultivation novels, a reference to Daoist beliefs. Pan has a similar opinion, “It’s personal growth, from loser to hero, which is common everywhere. But there seems to be a clear distinction. In the West, faith makes individuals more humble and obedient. But the implication of our culture seems to be that one practices to become stronger and more powerful.”

But, for all the content, originality, and relative youth of the genre, problems are amassing for this burgeoning fantasy scene.

Winter comes for traditional mediums

Much has changed since the heyday of Novoland. As a five-time winner of China’s highest award for sci-fi, the Galaxy Award, and one of the founding writers of Novoland, there is no writer that so represents the freedom of imagination of the Chinese fantasy genre as Pan Haitian. But these days, he doesn’t really write much; instead, he has turned his hand to screenwriting, investing, and production—from novels to designing toys and planning TV shows.

Novoland is still in his life, but the medium has changed completely. Partnered with Youku, one of China’s largest video websites, Pan’s company is writing a script for a planned seven-season web series depicting the final years of Novoland. “It’s [about] a new period…a time when Novoland is close to its destruction,” he says. “The conflicts during this time will be more severe and the larger ecological system of the world is going through certain changes.”

The same might be said about the literary scene for modern Chinese fantasy. Over the past five years, print fantasy magazines have died out. Their final attempt to evolve met with defeat when the most prominent fantasy magazine, Novoland Fantasy, ceased updating. Pan says that most serious fantasy writers in the industry have changed jobs to become screenwriters, get involved with production, or join other tangential occupations. In the traditional medium, the mantle of fantasy writer is all but abandoned.

“This is not an especially good time if you aim to write something really good, something that can be handed down for posterity,” Pan says. “First, there’s nowhere to get published. Even if you put it online, it’s hard to compete with [other] online fiction. Going into the film and TV industry to write scripts might be a direction you can go.”

Dismal as it sounds, this isn’t the end for Chinese fantasy fiction—quite the opposite if you travel to the online realm where fantasy writers can find both interest and profit. Popular with younger readers, China’s largest online reading and writing platform, Qidian.com, shows there’s life left in this genre; the top four categories of writings are all fantasy genres, adding up to nearly 900,000 pieces of work. A successful fiction series can generate 40 to 60 million hits over a few years. Online fantasy writer is one of the few jobs that can pay big in the Chinese creative industry; those at the very top can make more than the likes of Mo Yan or Liu Cixin.

They do this by selling the rights to their work, commonly referred to as IPs. The larger the built-in fan base of the work, the bigger the IP. Tangjia Sanshao, an online fantasy writer, ranked first on the 2015 Writer Rich List with 110 million RMB for his work Douluo Dalu. His fantasy world follows a protagonist’s fight to the top after he is transported to a strange new world in which people are able to wake their “martial arts spirits” in the forms of animals, plants, or objects. However, despite the 60 million hits in his pocket, he told a New York Times journalist that only two to three percent of his earnings came directly from the hits, while movie and game rights brought in the real money. He currently has ambitions to build his work into the next Disney franchise.

The popularity of Chinese fantasy isn’t limited to domestic readers—just go on SPCNET or Wuxiaworld.com to find abundant English translations of the hottest fantasy titles for foreign fans. With the accompanying Chinese idioms and cultural references explained within glossaries, these sites, easily garnering millions of hits a day, may just be China’s most powerful soft power weapon. The Great Ruler, Renegade Immortal, Battle Through the Heavens, a few hot titles on Qidian, all have English translations available on Wuxiaworld. All of these stories begin more of less the same way: the protagonist starts from humble origins (or is humbled by tragedy or betrayal) and the story follows his growth through constant level-ups and challenges until he achieves the ultimate success.

One notable feature of online fantasy fiction is their extraordinary length; works often and easily run to millions of words. For instance, Battle Through the Heavens contains 1,680 chapters and 5.3 million Chinese characters—that’s roughly 26 full-length novels. Updated in daily installments, writers have to crank out roughly 2,000 to 3,000 characters per day to keep their readers interested. Many resort to plagiarism under such pressure; some don’t even have the time to steal other people’s work personally since, with various “writing tools,” one can type in keywords and have entire sentences ready with automatic word algorithms and composition functions. The lack of a gatekeeper role in the process makes E. L. James seem like Shakespeare—at least she was original.

Nonetheless, the popularity of online fantasy hasn’t been hurt one bit by this depreciation in value, because all it promises in the first place is cheap entertainment. One of the earliest successes on Qidian was Dragon Route, which began as an urban fantasy with the protagonist expelled by his school, traveling to London to become a mob boss, and then he leaves earth to visit the realms of the immortal where he meets the ultimate boss battle and defeats the ruler of the universe—you know, that old chestnut. Writer Xuehongzhu knew his story got a little nuts; he put out an online statement: “I knew the story was quite…[wild] to the end. But I couldn’t help it. I wanted to end it on Earth, but my damn publisher forced me to continue.” He was referring to operators of websites like Qidian who are constantly pushing for more web traffic.

Anyone can write these stories, Pan insists, and in this way, Chinese fantasy is exactly like the original mission Novoland. “It’s a growing world, constantly taking on new writers. Those who join later could very well be more outstanding than the original founders. So this world will be an eternal one, and I hope it will grow to be an even grander and more spectacular world than we originally imagined.”

Rise and Apocalypse in Novoland

The fantasy trope of the journey from nobody to powerful being is an apt metaphor for Novoland itself. As an innocent online project, idea-sharing and collective creativity made Novoland one of the most ambitious and thorough writerly resources that ever was. But as the universe expanded in popularity, the Seven Gods started printing their stories in Fantasy World, a publication affiliated with Science Fiction World magazine, before founding their own magazine called Novoland Fantasy.

Among the Seven Gods are writers Jiangnan and Jinhezai, who became the most successful authors of Novoland. The former has published a six-volume series, Novoland: Eagle Flag, the linchpin of all Novoland fiction, focusing on conflicts within the human race; the latter achieved fame with his novels Legend of a Feathered Man, focusing on the winged tribe. In 2007, much like the inevitable end of a boy band, the collective had a public falling-out, each complaining of being excluded by others from strategic and editorial decision-making. Split into two groups, each independently developing Novoland projects since then, there’s still a rivalry today.

There were many interpretations of the incident at the time, but gradually, one narrative became dominant. As a 2014 feature in Blog Weekly magazine put it, “Jiangnan used to be the pioneer of Chinese fantasy literature…by betraying the very culture of this circle, he climbed to the peak of his career…the reason for his route to success is exactly the downturn of Chinese fantasy literature.”

They were speaking of Jiangnan’s acute commercial success and custom-made plots, which, as the old story goes, made him a sell-out and led to the decline of the genre. Jiangnan now makes frequent appearances on the Writer’s Rich List with his best-selling teen novel series Dragon Raja, seemingly with no interest in continuing Novoland anytime soon.

That being said, many pin the problem on something even closer to home. “Novoland is very good, but it’s like filling a Western skeleton with Chinese flesh,” an anonymous user stated on Zhihu.com, the Quora-like question and answer site. “I don’t think it’s an authentic Chinese epic fantasy, in fact, I haven’t read a single authentic Chinese epic fantasy yet.”

From the time of the New Culture Movement in the early 20th century, the spells and magical creatures so prevalent in traditional shenmo (“gods and demons”) works of fiction were seen as superstition and products of a feudal society that hindered modernization. After the founding of the PRC, the Communist Party, officially atheist, encouraged realism in art over supernatural themes and stargazing. There is a satirical saying about the New China’s distaste for the supernatural: “After the founding of PRC, no one was allowed to turn into an immortal.” The end of the Cultural Revolution saw the relaxation of these ideological restraints, though fantasy-related content is even now carefully kept at a healthy “dosage” by regulations from the State Administration of Film and TV.

This half-century of repression of the genre has created profound consequences for creators and audiences of fantasy in the present day, caught up between the selfless project of trying to carve out a distinct imaginary space for Chinese fantasy and the reality of having to make it sustainable and personally worthwhile. These deeper schisms in the fantasy fiction community were behind the fallout between Novoland’s creators, and they are still reverberating.

Ancient history to modern fantasy

When asked to name his ideal Chinese fantasy world, Professor Zheng doesn’t point to any recent work. “My favorite scene is when the Monkey King, the headstrong, self-proclaimed ‘Great Sage Equal to Heaven,’ was despised and lost face in heaven. He then started to behave like a naughty middle school student, stealing peaches, royal wine, and pills of longevity, stirring up trouble in the royal banquet. With his golden cudgel and his ability to change shapes, he fought god after god from heaven to hell, making the entire universe an arena to release his vitality…It’s the eternal ode to youth.”

Unlike others who are bemoaning the quality of fantasy fiction in the age of official restriction, online revelry, and the death of traditional publishing, Li Qiqing (penname Barrel Rider, see page 10) believes we are already seeing authentic Chinese fantasies growing right out of ancient tradition—but also, it doesn’t really matter where our inspiration comes from. “Time-travel, training to become immortals, wuxia, fox spirits, you can say these are all influenced by our literary heritage,” he says. “On the other hand, tomb-robbing stories are not from either Eastern or Western traditions and they are still popular.”

China does have a rich fantasy literary tradition that can be traced back to the Classic of Mountains and Seas (《山海经》) in fourth century BCE, an ancient atlas of mythic geography, strange lands and magical creatures. In the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), chuanqi or “Tales of the Marvelous” was the fashionable form in which to tell extraordinary stories, many with supernatural elements. In the tenth century, the Extensive Records of the Taiping Era (《太平广记》) was compiled, a treasure chest of 7,000 tales of deities, immortals, ghosts and priests, from which Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) author Pu Songling of Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (《聊斋志异》) got his inspiration.

It would seem that today it is almost impossible for writers to create within a single tradition in the global age, but perhaps that’s what fantasy needs to stay imaginative and continue growing.

Regarding the controversy about online fantasy, at least, Li is not concerned. “A few hundred years ago in Ming and Qing dynasties, when novels first appeared, people of the time though they were garbage, too,” he says, “Due to computers and internet, anyone can write nowadays…we should celebrate the fact that more people can take part in writing. There’s no need to worry about too much garbage. A few hundred years from now, our time is surely going to be regarded as a better era for writers, with many classics coming from this age.”

Wildest Fantasy is a story from our issue, “Wildest Fantasy.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.