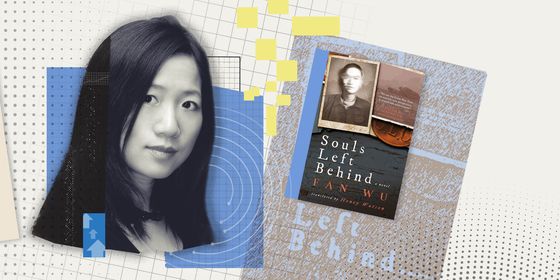

Author Iron Head writes about the lives of youths who’ve grown up at the bottom of society

A giant smokestack stuck straight up into the gray afternoon sky. On this day in late May the only people on the concrete plain were two deaf children who stood facing each other, quietly and carefully kicking about a multi-colored ball on a piece of ground that extended out in the shape of a fan from the factory. Worn down from years of use and speckled with pits and hollows, the ground looked like the skin on the face of a sickly patient on his deathbed.

As three trucks drove by the edge of this terrain, they kicked up bone-colored dust from the rotted earth, a scene that seemingly transformed a visual sensation into a tactile one, that of talc powder. A hunchback suddenly stopped in his tracks, raising his head to look upon the giant arch at the entrance of the factory; the characters had faded, or perhaps his eyesight was failing him. By the time he turned to walk quietly away, the two deaf children had already disappeared from the landscape.

Against a quiet and hazy backdrop reminiscent of a silent dusk upon the desolate outskirts of a city, a bell rang, and the factory gates slowly opened to reveal a group of workers finishing their last day on the job, all laid off. Their faces carried an expression that embodied reticence, with only a few trying to conceal their sense of confusion and despair with exaggerated complaints, belied by the looks of loneliness and desolation in their eyes.

At a time when common people around the country were losing their jobs, Mr. Zhao was just one in a giant crowd.

The cloth sack tied to the back of Zhao’s bike, filled with all kinds of personal objects, bulged in various places; the sound of metal spoons and enamel cups clanging within blended with the dull scraping that the mudguard on his back wheel made whenever it met a pothole.

The workers flowed out like a stream, sticking to the shade of the large poplars on the side of the street, gliding forward in small groups on their bicycles, all with a sack hanging from their handlebars for lunch.

Zhao felt he was just too damn unlucky, the memory of the funeral a few years ago still fresh in his head, his wife’s plump face floating in his mind, as if a hot compress had been applied to his skull. Whenever he had thoughts like this, he would hear a cold whistling in his ears, the sound of a blizzard in northeastern China with a crazy woman lost within. After her death, Zhao would always describe the story of her passing as such:

“She suffered a mental shock, always believing her daughter hadn’t died, always wasting her time trying to get fortune-tellers to reveal her whereabouts.”

The family was originally poor yet happy, but when their schoolgirl daughter disappeared, the previously quiet wife came to suffer from dementia, and froze to death in the snow. Zhao thought about how his son was already in middle school himself, how quickly time passed, and how in a few years he might himself be bedridden, like a cripple unable to take care of himself. How his son only knew how to mess around, and would leave him to die tragically. Whenever Zhao had these kinds of thoughts he became quiet and dispirited. Now that he was laid off, he was an aged single father who still had to take care of a foolish son.

Zhao frequently thought about poisoning himself, about his departed loved ones, about his suffocating life. He truly wanted to drink a bottle of liquor mixed with insecticide—he didn’t lack the balls to kill himself, even though it was admitting he was a loser afraid of life. Death was a great release, but he couldn’t die because he still had a son, Zhao Huajun.

Zhao rode his bike into an alleyway and thought again of the reality of being laid off. He felt lost: What would he do tomorrow? What would he do in the future? This was a difficult situation to be in for a man in his 40s. He pushed his bike into the courtyard and saw his son, Huajun, squatting over an old alarm clock that he was disassembling.

“What are you taking it apart for?” Zhao asked.

“It’s broken anyway,” said Huajun, barely looking at his father, fiddling with a screwdriver in his right hand.

Zhao didn’t have anything to say, and just placed his hands on his hips as he sighed deeply, under the apricots.

“Buy me a bike,” said Huajun as he suddenly raised his head.

“Buy you a bike? Why do you want me to buy you a bike?”

“They all have them.”

“They?”

“Yeah, they all have bikes,” said Huajun impatiently. “My classmates, my friends, Shaojun, all of them have bikes, and they ride them everywhere, and I don’t, so I can’t join in anymore.”

Zhao could hear the sad tone in his son’s voice as his throat choked up, and suddenly felt sorry for him. “Just take mine. I don’t need it anymore; got fuckin’ laid off.”

“I don’t want your bike,” said Huajun as he furrowed his brow, speaking with scorn. “Besides the bell which doesn’t work, every other part squeaks and creaks. I’ll be laughed at, riding a junker like that.”

Well, shit. Hearing his bike mocked by his son, who didn’t even pay attention to the news of him being laid off, made him furious. He pointed at his son’s head: “Well, in the future, we won’t even have food to eat! I get laid off and you want me to buy you a fucking new bike? Tell me, where’s the money going to come from? You can starve, you little jerk!”

“They all have them!” Huajun yelled back, unable to control his anger and pain.

“Well, they can all go to hell!” bellowed Zhao. “Piss off! Get out of here! If you’re up to the task then pay your own way, make some money, buy a bike, buy whatever the hell you want if you can afford it. Buy a fucking tank for all I care. Fucking little Yama Raja up in here! Get out of my sight, giving me shit when I’ve just been laid off…”

Huajun stood up suddenly, very straight, like a sculpture in a park, gripping the screwdriver tightly in his hand, eyes full of rage. He really did appear like some kind of statue, a brave warrior with a red-tasselled spear.

Zhao sat squarely upon a rock underneath the apricot tree, and took out a wrinkled pack of cigarettes, pulling placing one in his mouth, exhaling heavily. Huajun looked sideways at his father, angrily puffing out his cheeks before running out of the courtyard as his father lit the cigarette.

Zhao saw his son running out with the screwdriver and wanted to tell him to leave the tool at home, but suddenly he felt very tired and down, and gave up on the idea. It was just a screwdriver.

As he prepared noodles in the kitchen, Zhao thought about his son, and noticed that it was already dark outside; the news had finished. He placed a big white bowl of food on the couch as he watched TV—the overhead light wasn’t on, and the screen lit up the room in mysterious ways. By the time the second episode of Romance of the Condor Heroes had finished, Zhao was already sprawled diagonally upon the couch, empty bowl and chopsticks sitting ominously upon his chest.

By this time Zhao was dreaming. He rarely dreamt, never more than a hundred dreams in a year, so each dream moved him deeply. This night, he dreamt of his youth, the difficult years when food was in short supply and meat was a luxury. Almost every day he’d sit on the stone roller and zone out, sometimes enjoying the sight of a girl who would pass by, a beauty with two braids named Wang Yan, a few years older than him whom he loved from afar throughout his youth. In his boyhood Zhao would fantasise about her often, spending countless nights having all manner of thoughts, sometimes pure, sometimes dirty, hard to believe, illogical. All manner of unimaginable scenarios played themselves out in his mind, bloomed, and withered.

Li Na stopped as she passed by the window of the student canteen, and turned her head from side to side as she checked herself out. Although it wasn’t a mirror, she could see a fuzzy image of herself in the glass, and only after she checked that her fringe was (or at least seemed to be) set properly was she able to continue walking. She had a bag over her shoulder, maybe expensive, maybe not, and came to a halt at the entrance to the campus—it was clear that she was waiting for someone.

The sky gradually darkened and she became impatient, worried. She furrowed her brow slightly as she observed the students coming and going, sometimes walking in little circles, but her most frequent action was to take out her mobile and check the time. Suddenly, her phone rang, and she hesitated when she saw the name that appeared; she couldn’t help but look about in unease; either way, she couldn’t refuse the call. She heard her boyfriend’s voice jump out anxiously from the speaker:

“Where are we going?”

“Where are we going?” said Li Na. “Nowhere”.

“But today’s a special day.”

“Special day?” asked Li Na. “It’s June 1st, Children’s Day.”

“Yeah, today’s Children’s Day, tomorrow is your birthday. You’re from around here, so you’ll definitely be going home to celebrate, right?”

“Yep.”

“Well then, we can only celebrate your birthday today; where should we go?”

“Oh.” Li Na forced a laugh. “Well then, make it up to me some other time, honey. I can’t go out today, I don’t feel well. I think I might have a fever. I’ve got no energy, I don’t want to leave the room, I need to rest up here as I have to go home tomorrow.”

“Are you sick?” The voice was full of worry. “So sudden! I’ll come straight to campus to find you. Do you need medicine? What do you want to eat? Where are you, are you outside?”

“No.” Li Na pressed the phone tightly to her face. She turned her back to the road. “I’m in my dorm with the window open, standing next to it; it’s too hot, but there’s no wind. Don’t come, I just want to lie down in bed, there’s nothing you can do and you’ll be bothering me. I have medicine here; if I want to eat something, Linlin can go down and buy it for me, don’t come.”

“No, don’t worry, I can go buy you some fruit. What do you want? I can drop it off downstairs and Linlin can come and get it.”

“Just for fruit? No need to come all the way for that, really, listen to me.”

“Well, it’s not like I’m busy.”

“I told you not to come, so don’t come, no need for all this rubbish.” Li Na became annoyed, but quickly realized that her behavior was inappropriate. She softened her voice, and put on a cutesy tone: “My dear, I just want to sleep. I’m super tired, I can barely open my eyes.”

“Well…all right. Rest up, and call me if you need anything. OK, yeah, bye.” He gave a disappointed laugh.

Li Na hung up and tightly gripped the phone in her hand and then let her arms hang limply as she relaxed, sighing. A feeling of guilt crept over her, entangled her like a growing vine, entering her nerves and the maze-like network of her capillaries. She was struggling against falling into a state of nervousness and unease. She picked up her phone; she had to call the guy. She’d waited too long already, she needed something new to happen, to wipe away her bad emotions. But he didn’t pick up, he turned down the call—the shock filled every pore on her skin like a winter chill.

A car suddenly pulled up. Her eyes frowning down at her phone, Li Na saw the license plate first: LIAO-T8585A. The face of a suave-looking middle-aged man appeared in the window, chuckling at her.

“You missed me,” said the man. “I guess I’m irresistible to you.”

“Why did you take so long?” Li Na put her mobile in her bag, and quickly walked over. “Modesty is a virtue of which you only have a little bit, and, what’s more, I didn’t miss you. I was calling because I’m hungry.”

“What you’re saying is that few men my age are as smooth as me. Good machines require good maintenance.” The man cocked his head slightly to the side as he watched Li Na enter the car, laughing as he put his hand on her shoulder. “You must understand, when I see your number on my screen, I lose myself. You’re so pretty, I just freeze up.”

“Pretty? Damn straight! Honesty is your strong suit,” Li Na said with confidence. “Come on, let’s roll, I’m starving.”

“How’s that boyfriend of yours?”

“Why do you have to bring him up?” asked Li Na, annoyed. “Don’t ruin my mood all the time, okay? Ugh, you always make me feel so guilty, so bad.”

“I’m jealous, you should be happy,” the man laughed as he turned the steering wheel. “A guy like me who’s been through so much, being jealous of you, jealous of a young university student. You should feel good.”

“OK, get off your high horse. I hope he goes off me. I don’t want to dump him, we’re high school classmates, our other classmates would have a field day if they found out. It’d ruin my reputation.”

“You don’t think you might be overthinking this a bit?”

“Either way, it’s not a role I want. He needs to make the move. All I can do now is treat him a bit shitty, make him feel like I’m ignoring him, make him dislike me.”

“This is why guys say ‘mo’ honey, mo’ problems’.”

“Screw you!” Li Na punched the man’s leg. “I’m not your honey, your wife is your honey. I’m a pure little girl.”

“Spare me. We still have to eat.”

Zhao opened his eyes, and reached for the alarm clock, although there was no headboard and no clock there—he was lying on the couch in the sitting room. His upper eye socket ached slightly, and his tongue was dry. He noticed it must be early morning from the color of the sky as he suddenly realized he didn’t need to go to work. Tired, he sat up cross-legged on the couch and saw he forgot to close the curtain on the south-facing window last night. The early-morning light flowed dimly through the window as clear birdsong sounded in the courtyard. Stepping on the backs of his slippers, he walked over to Huajun’s room to see that the bed was empty. He didn’t come home last night, thought Zhao. His mood, already bad from being laid off, turned worse.

Zhao opened the door of the house and stood in the courtyard. The clear air was like ice-covered steel in his lungs. He breathed it in deeply as he felt a deep loneliness. It wasn’t hard to imagine that a few hours later, when the sun was its highest point in the sky, the holiday atmosphere would be in full bloom there. Zhao slowly walked around the giant plaza, looking tired as he held one hand in the other behind his back. A flock of doves flew by smoothly through the rays of sunshine, moving about like a cloud in the empty plaza, as monks hurriedly walked in and out of the temple.

The fountains hadn’t been turned on yet, and Zhao sat on the cement steps, noticing a woman next to the brown benches carrying a vegetable basket. On the morning of Children’s Day, it wasn’t unexpected to see Wang Yan, now a woman a few years his senior, since they both lived in Tongcheng; it made sense they’d run into each other from time to time. He’d just been dreaming of her as a young girl, head low, walking out from behind a wall covered in vines after the rain. She walked towards him with heavy steps, basket in hand, mind seemingly elsewhere.

“Ms. Wang!” Zhao stood up straight, and raised his arm.

“Little Zhao.” Wang Yan laughed clearly, and she picked up her pace: “What are you doing here alone?”

“Oh, just taking a walk,” said Zhao. “How are you?”

“Doing okay.” Wang Yan shifted the basket to her other hand. “You’re not working?”

“Got laid off.” Zhao answered here with fake levity, noticing at the same time the pieces of scallion in her basket. “How’s Old Li doing at the factory?”

“Not good,” Wang Yan shook her head earnestly. “Also laid off, recently. He managed to find another gig, it’s easy, but the salary’s low. It’s OK, though. We only have one daughter, we have enough for her dowry. The rest is enough for us to live on.”

“Well, yeah, that’s how it goes these days.” Zhao thought for a bit. “Isn’t Li Na graduating soon?”

“No, she still has two years.”

“Oh, I thought she was almost there.”

“No, two more years, and tomorrow’s her birthday. She’ll be 22,” Wang Yan spoke happily. “Time really goes by quickly. Before I know it my daughter’s already this old. When we were young…forget it, it’s crazy. So fast.”

“Yeah, if my daughter were still alive, she’d be older too—about the same age as your daughter.” Zhao looked at Wang Yan, seeking agreement.

“That’s true.” Wang Yan nodded her head. “Ah, it’s been so many years, in just a flash; so fast. Well, I should get going, I need to make breakfast. Old Li’s almost off work. If you have time, you should come over , have a few drinks with him.”

“Sure!” Zhao answered.

Huajun appeared at Wang Xiaozhu’s house, when a group of kids were watching cartoons in a cramped room inside. In the northernmost corner of the room was a drunken middle-aged man snoring as he slept. There were a number of flies on the curtains, covered in dust—it wasn’t clear if they were dead or alive. Yellowed newspapers were pasted on the uneven walls, and a black-and-white photo in which only a waving hand was visible.

Huajun stood behind some other boys’ shoulders, and happily watched the cartoon. When it ended, the others turned to each other and started discussing the show loudly; nobody had noticed that Huajun was there. They asked him when he’d come there, and why he had a screwdriver in his hand.

“I’m gonna mess up Xiaohai.” Huajun puffed up his cheeks as he answered them.

“Quit with your bullshit,” said Zhu Liang. “You run your mouth when he’s not around, but if Xiaohai heard what you said, you’d be in trouble.”

“It’s already dark, you’re not going home?” Through the window, Huajun could see the rest of the children hopping onto their bikes and drifting away.

“I’ll go back, but I still haven’t eaten,” Zhu Liang rubbed his nose. “I can’t go with them. I don’t have a bike. Gotta take the long walk home.”

“Me too,” Huajun groaned, depressed. “Fuck, my dad won’t buy me one, he even suggested I ride his fuckin’ junker.”

“We can make some money together, and go and buy new bikes for ourselves.” Zhu Liang and Huajun walked shoulder to shoulder into the dark alley.

“How?”

“Selling iron,” Zhu Liang said. “Xiaohai and the others did it, go to the old machine factory in the north. At night there’s only one guy on guard duty, we can be a good team.”

“Ah, I get it, I get it.” Huajun nodded, looking at his own feet. His brain was turning over in his head.

“Each of us can have our own bike, ride it to wherever we want, it’ll be awesome.”

“Will this really work?” Huajun could already feel the beauty of the potential outcome, but he didn’t feel good about stealing.

“It’ll be fine, Xiaohai and the others have done it. The factory has nobody looking after it; it’s practically deserted.”

When he started this job, Old Li used to patrol every corner of the factory each night with his torch, but now he was far too lazy to do so. There wasn’t even anyone here anymore, so there was no need to worry so much. His old radio was there at the head of the bed, playing the tales told by Shan Tianfang.

Old Li sat with his back against the bed with a cup of liquor in his hand; an open window was next to his right ear; it was quiet outside, just the sound of crickets. He would drink for five or six hours, with only the radio and liquor to keep him company through the long night. He spent a lot of time thinking about the past, a time shrouded in gold mist, the savage memories already unclear. In his memories, Li wasn’t a watchman but a worker, a young man full of energy, sometimes playing with a slingshot shooting sparrows.

Li, full of emotion, took a sip of liquor and put his two hands on his knees. Before him he’d set up a little table with two plates and a large bowl upon it. The bowl was full of fried peanuts that had already gone soft, and one plate was covered in pickled radish, while the other had some shallots. Noticing the tale was already over, Old Li took the radio and twisted the knob to look for a station, static mixing with random noise.

The sound of metal falling gave Li a start, causing him to sit up straight and listen carefully. He made out footsteps and hushed voices. He picked up the iron bar leant against the bed, and jumped into the night outside.

“Who’s there?” Li ran southwards as he yelled.

Two people were scrambling to climb over the wall.

“Don’t move!” Li raised the iron bar as he quickly approached them. After a few failed attempts, he saw them give up and turn around slowly, their faces clear—they were two boys of maybe 15 or 16 years of age.

“Who are your parents?” Li yelled. “You fucking dare to come and steal?”

The boys hung their heads, saying nothing.

“Real tough, huh.” Li reached out and grabbed one of the boys’ arms. “You two are coming with me, let’s go! Police station time.”

“No!” The boy struggled to stay in place, begging him. “Please, please.”

“No dice! Let’s go!” Li pulled forcefully at the boy’s arm, having already raised the iron bar with his right hand. He threatened the child: “You don’t think I’ll bash your head in? Come the fuck on, let’s go.”

“Fuck you, man!” The other youth rushed forward and screamed sharply as he jabbed something into Li’s chest.

“Argh!” Li suddenly felt a sharp pain as if lightning had struck him there. He threw down the iron bar, released his grip on the boy’s arm, and pressed his two hands to his chest. He knelt down, moaning in pain.

“Run quickly!” The boy whose arm has been pulled dragged the other boy; they ran away.

Li sat down squarely, moaning continuously like a wild boar as his strength gave out and he slowly relaxed. He closed his eyes as he laid down, mumbling hurriedly. Soon, he ceased moving entirely, as if sleeping peacefully under the clear moonlight—except for the fact that there was a screwdriver protruding from his chest.

To the north of the plaza was the tall red wall of the temple, under which Zhao sat on a white stone, spacing out. He saw the young parents leading their children, and underneath the giant arch, a few men with cameras carefully directing their wives and children to pose.

The fountain was already in full force, sending columns of water shooting high in the air, making the children cry out with joy. The water reflected the sunlight and sent sparkles flying everywhere. More and more people came about, with complete, happy families milling about like ants; their happiness seemed to spread like fire, around the old men with long beards waiting under the wall to read people’s fortunes.

Zhao threw another cigarette butt to the ground. He’d already seen the plaza go from deserted to packed, and thought over all the relatively major events in his life in detail, especially those who had died—relatives, friends, his wife, his daughter, people from the factory. He thought about their expressions at various moments, smiling, contrite, disappointed, sad, lonesome, pained. This was how life went—he wasn’t extremely old but he wasn’t young, didn’t have a shot at prospering, what did he hope for in life? What did he hope for his child? He thought about Huajun again—where was that little fucker?

Zhao still hadn’t eaten, but he wasn’t hungry. He felt like his stomach was full of cigarette smoke, pushing against the walls of his stomach like air in a balloon. By the time the streetlights lit up, Zhao felt that it was time for him to get a move on, go get something to eat. He felt apprehensive for a second—he’d spent the entire day at the plaza, observing the purity of the children and happiness of the families.

Zhao went to the Pig Head Diner to drink a bit, and eat a bit of pig’s cheek and trotter. This restaurant was opened by people from out of town—supposedly from Heilongjiang—who’d given their restaurant a rather unusual name: Pig Head Diner. This name was quickly engraved into the minds of the people of Tongcheng: walking past the plaza towards the train station, one could quickly discover this restaurant, looking like a guesthouse from a movie of antiquity, its interior populated with dark wooden tables and large vats of liquor in the corners. Zhao knew the restaurant was quite popular, and on holidays would be packed with diners enticed by the smell of pig’s head from across the street. People came to drink, eat, and chat about their hardships over the continual din inside.

The restaurant wasn’t expensive, and it had character—very much an everyman’s restaurant. Before he was laid off, Zhao would frequently come here with his colleagues to drink after work.

The Pig Head Diner was full of customers. Zhao couldn’t find a table, so when a young man let him, he sat down across from him. Zhao liked this kind of atmosphere: not high-class, just a relaxed environment in which one could sit down, enjoy, and drink. Everyone was unrestrained, speaking in loud voices as to be heard by their companions over the roil of others’. Zhao gnawed on a trotter and enjoyed his drink, satisfied, suddenly feeling quite happy, having already drunk a good deal, just like the young man across from him. He could see something troubling was on the man’s mind, that he was drowning his sorrows in liquor. Zhao didn’t speak, even though he’d been sitting across from him for an hour and a half.

Finally, the young man was drunk. Looking at him, Zhao thought he must know he was drunk. The young man suddenly returned his gaze, eyes shining, filling with tears, and spoke: “I was planning to do them.”

Zhao looked up at the young man, but didn’t say anything.

“Really, I was planning to do them.” The young man took a folding dagger out from his pocket, and tapped it on the table, avoiding Zhao’s gaze, looking at his little weapon, tongue quivering. “I mean, of course I knew; I’m not stupid. I’m poor, what can I do?” Besides castigate himself, what could he do?

“So you’re a university student?” Zhao finally spoke.

“She shouldn’t have lied to me.” The young man spoke, hurt and angry. “I’m not stupid, how could I not know? I made a call, talked to Linlin, everything was easy to figure out. I’m 20-something, I’m educated, am I that easy to fool? I’m not an idiot, I know everything, but what could I do? I’m not brave, I can’t be ‘hard core,’ so I’m not a mover or shaker. I’m too nice, no; too much of a pussy, and I’m broke, so how the fuck can I live with myself? I can’t die, there’s nothing, nothing I can do, I mean, what can I do, really? What can I do?”

Zhao didn’t pay attention to him, and instead looked elsewhere at the middle-aged men, faces beet-red from the alcohol, talking loudly as they smoked and drank. The youth’s voice blurred, became simply a buzz in his ear. Shortly after, he turned to look at the young man, head on the table, silent.

It was already quite late, yet people were still walking in small groups outside the train station, carrying luggage as they scurried about under the pale white light of the streetlights. When Zhao left the Pig Head Diner, the young man was still lying at the table, not making any noise, like a wearied traveler in deep sleep. Zhao knew it was very late, and that he should go home, as he staggered out of the door of the restaurant to see pedestrians in the distance, only dark outlines to him.

A group of youths, cigarettes in their mouths, walked by, full of energy, bouncing about, talking and laughing. Zhao focused to see if Huajun was among them, but was met with disappointment; he didn’t know if his son had returned home yet.

Approaching the intersection in front of the stock exchange, he saw a group crowding around something: a traffic accident. Two prominent-looking police cars were parked over there, the vehicle involved surrounded by policemen and a few middle-aged men and women speaking loudly. He couldn’t see much of the accident, only the vehicle’s rear plates—LIAO-T85 something—so he drew nearer. Elbowing his way forward. Zhao was surprised to suddenly see his son, Huajun.

“Zhao Huajun!” Zhao ran forward, and waved his hands as he cried out.

“Dad!” As Huajun stood by the police officers, he turned to face Zhao.

“Where did you go? What were you doing?” Zhao pointed at his son’s nose as he scolded him.

“Zhu Liang was hit by a car.” Huajun pointed to a body, prostrate upon the ground.

“He was hit?” Zhao walked a couple paces closer, and strained to see.

“Dad…” Huajun stuck his hand out and tugged at his shirt.

“Yeah?” Zhao turned his head to look at Huajun.

“I’m hungry.” Huajun spoke, his small Adam’s apple shaking.

Author’s Note: “The Pig Head Diner” was completed in 2009 when I first started writing, and I enjoyed writing about the life I was familiar with. Northeast China used to be the PRC’s cradle of industrialization, filled with factories, while factory workers had high social status. In the late 1990s, when massive layoffs hit, these once-glorious factories closed down. Workers all lost their jobs. The entire Dongbei region quickly declined. Those unusual times led to unusual lives and stories, values, and social environment: The desperation of the older generation, the losses and desires of the new generation, the impulsive yet fragile youths, all affected by the industrial decline. In this story, I wrote realistically about the people around me. They are only ordinary, but when putting their ordinary life into words, cruelty manifests.

The Pig Head Diner is a story from our issue, “Wheel Life China.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.