Contemporary art battles to find a place to grow in the face of regulations and rising property prices

About an hour’s drive to the east of Beijing, the village of Beisizhuang bears little resemblance to the bustling skyscrapers of the city. Tangles of cables hang low across narrow alleyways of gray brick walls, and there is little sound aside from swallows chirping and bees browsing plots of vegetables.

But this, and several other villages in the township of Songzhuang, are the site of a last stand. Located on Beijing’s far eastern outskirts, adjacent to the province of Hebei, the township was at one time part of a proud tradition of avant-garde artist communes—places where contemporary artists could find cheap accommodation and develop their creative niches in social freedom and rebellion. But as regulation and gentrification have tamed China’s wider contemporary art world, so are these communities becoming tamed too.

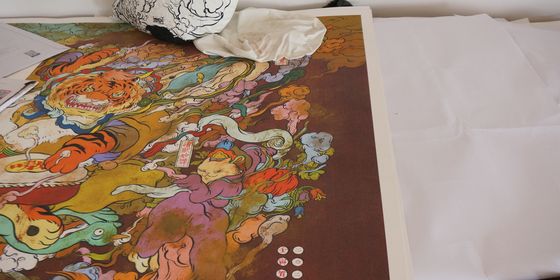

That the village will be redeveloped is “everyone’s biggest worry right now,” artist Song Yonghong, a veteran painter and a former art teacher, tells TWOC in his high-ceilinged studio within Beisizhuang. In 2015, Beijing’s municipal government announced it would relocate to Tongzhou district, about five kilometers away from Beisizhuang. The move officially began in January 2019.

Song had arrived in Beisizhuang as a refugee of urban development, with “nowhere else to go,” in June 2017. The municipal government had demolished another village he was living in to the northwest of Beijing, part of a city-wide clean-up of shabby migrant settlements.

The bulldozers also came in the same month for Heiqiao, the legendary artist commune in Chaoyang district, forcing residents like Yang Song to flee. “Songzhuang is the last place [in Beijing] where there are many artists gathering,” he tells TWOC.

They aren’t the only ones who were given no choice. In 2010, there were over 20 artist communes in the city, with populations ranging from a handful to tens of thousands. Dozens dotted around the 798 Art District (an industrial compound revamped into a high-end collection of galleries and boutiques) were cleared in 2010, as well as the so-called “iron ring” (Huantie) to the city’s northeast.

But if these are refugees, they’re certainly well-treated ones. Both Song and Yang rent big, well-heated new lofts that stand out from the smaller bungalows of their local neighbors. For one veteran Beijing gallerist, who wished to remain anonymous, the community has grown indulgent. Though he believes Songzhuang still harbors some talent, it is also “a piece of incest, as the artists rather tell each other how good they are and drink together, instead of criticizing each other and pushing each other to grow…So whatever opinion comes out of Songzhuang, I do not take it seriously.”

There is a certain prestige to Songzhuang, given its heritage in contemporary art history. Communities like the Xiamen Dada and the “Southern Artists Salon” in Guangzhou through the 1980s, or Beijing’s Yuanmingyuan commune of the 1990s, were the origins of Chinese contemporary art, representing “the inner desire of people for freedom in artistic creation,” according to Song.

What’s Next for China’s Once-Thriving Artist Communes? is a story from our issue, “Call of the Wild.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.