A new book by historian Yajun Mo reveals the through-lines linking Chinese travelers, past and present

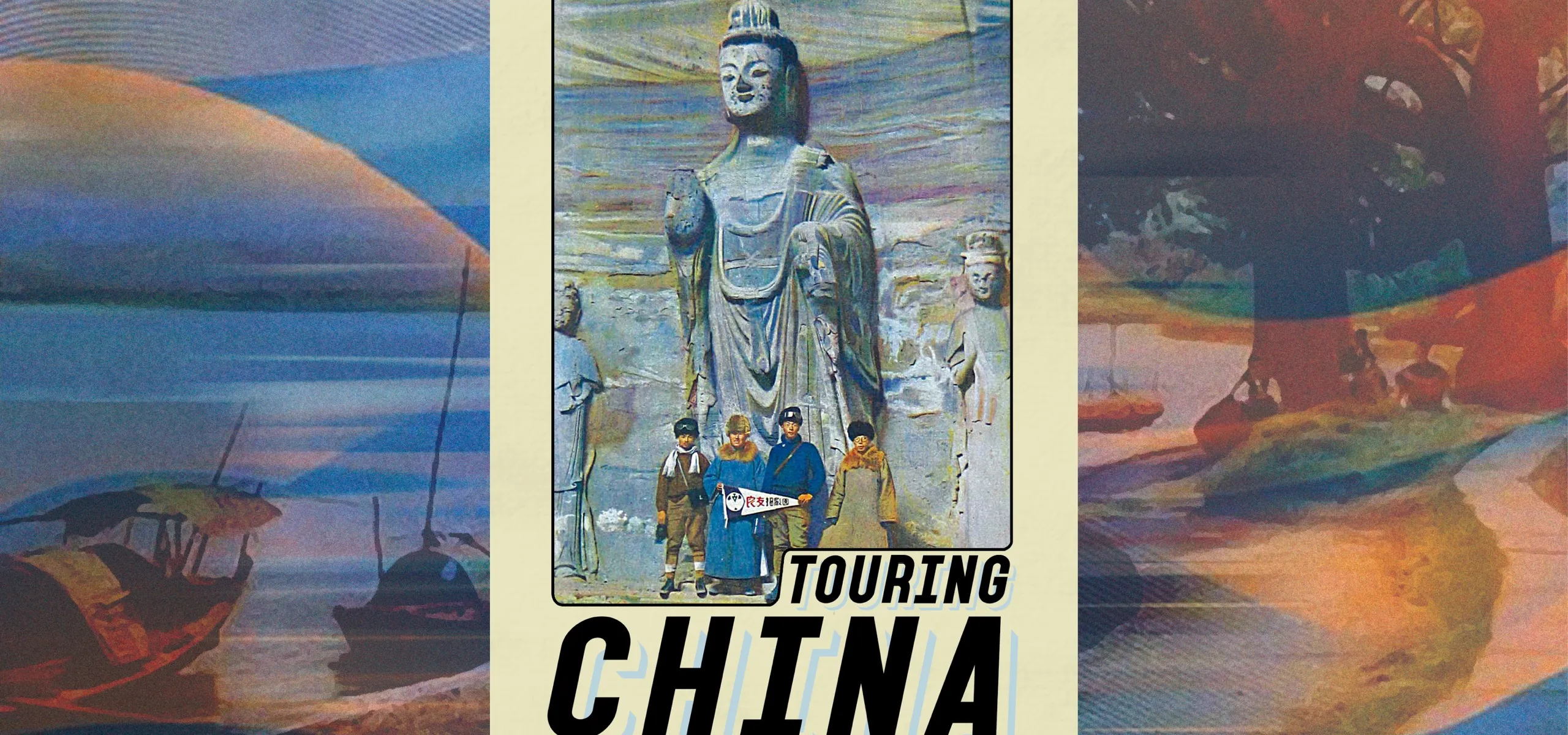

Mass tourism in China is not a new phenomenon. In Touring China: A History of Travel Culture, 1912-1949, historian Yajun Mo explores the development of the travel industry in China in the Republican era, a time when urbanites took to the rails, roads, rivers, and even skies to see the sights of their nation—and eerily prefigures some of the challenges facing China’s tourism industry a century later.

Mo, an associate professor of history at Boston College, describes how tourist activities in the years before 1949 “allowed Chinese citizens to redefine postimperial China in a period of dramatic political change.” Modern transportation allowed tourists to explore once difficult-to-access regions. New business models, including the first major domestic travel agency, the China Travel Service, offered ticket services and tour packages to cater to demand.

The expansion of print media in early 20th-century Chinese cities led to popular specialty magazines like China Travel, whose travel articles and photographs inspired readers to plan their voyages. Mo argues participating in travel and tourism was a novel form of leisure for a burgeoning Chinese urban elite. Travel as recreation was seen as vogue and Western, a way to display wealth and allow travelers to present an image of sophistication and modernity.

According to Mo, Chinese travelers were also part of a zeitgeist, to build a coherent and unified nation from the ruins of the Qing Empire. Scholars and researchers—as well as more adventurous tourists—traveled into the frontiers of the new nation.

Tourism in China’s southwestern regions after the Republic of China moved its capital to Chongqing in 1937, and to Taiwan after the war against Japan ended in 1945, allowed patriotic tourists to symbolically claim sovereignty over contested areas. As Mo argues, “These diverse forms of modern travel contributed to the imagination of China as a congruent national space.”

Tourism was not only a way for Chinese to define the boundaries of their own nation, but to reclaim their country after nearly a century of foreign imperialism. Early 20th-century Chinese travelers described by Mo shared their transportation and destinations with foreign tourists and expatriate residents, the latter seeking to re-create Western-style tourism spaces inside China.

Particularly galling for Chinese travelers, writes Mo, were policies of racial segregation for accommodation and transport, creating “racial boundaries that differentiated Western-style tourism spaces from the rest of China.”

Colonialism and colonialist attitudes have long played a part in the evolution of the travel industry. As early as the 18th century, Thomas Cook promised his clients the means to see the magical sights of the British Empire while assuring they would be protected from being ripped off or robbed by ungrateful locals. Even today, colonial nostalgia continues to play a role in attracting visitors to Asia—the official website of the Astor in Tianjin lauds how the historic hotel “evokes the romance of a bygone era.”

Chinese travelers were not immune to some of these same colonialist attitudes. Mo describes how the Chinese academic Liu Bannong, who journeyed to northwestern China with the Swedish geographer Sven Hedin in the 1920s, complained about Hedin’s use of the term “expedition” (translated as 远征) to refer to their mission. Expeditions, as Liu Bannong and his Chinese colleagues understood them, “were carried out among the ‘blacks and savages,’ and it would be insulting to use the term in China, a country with an ancient culture,” Mo writes.

Yet Hedin and Liu shared an attitude toward the regions through which they were traveling. The European explorer and the Chinese scholar considered the frontiers of the old Qing Empire as places to be explored. Liu and the other Chinese scholars on the trip “had no qualm about considering the non-Han peoples in the Northwest as less civilized,” writes Mo.

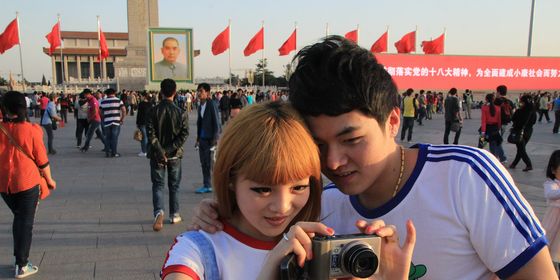

While the book does not cover the post-1949 period, Mo’s research suggests some interesting continuities between tourism in China in the early 20th century and today. There were over 3.43 billion domestic trips in China last year, a 19 percent increase over 2020. The China Tourism Academy expects that trend to continue in 2022, estimating domestic tourism will be at about 70 percent of pre-pandemic totals this year.

Many of the trends that drove the rise of tourism in an earlier era are part of the 21st-century expansion, including greater disposable wealth, increasingly sophisticated media, and significant infrastructure improvements that make travel easier and destinations more accessible. While overt racial segregation is no longer an issue between foreign and Chinese tourists traveling in China, similar conflicts over issues of sovereignty, representation, and travel culture persist into the 21st century.

On modern international travel websites like Trip Advisor, non-Chinese travelers to popular destinations like Lijiang Old Town in Yunnan province, and the karst mountains surrounding Yangshuo in Guangxi, lament “hordes” of Chinese tourists or offer wistful reminisces of these places before they were “discovered” by domestic travelers. International travel guides to China warn about the creeping influence of commercialization and a lack of “authenticity.”

At the same time, portrayals of western China and non-Han nationalities in contemporary Chinese travel literature reveal a similar fixation on the sensual and the exotic. Domestic travel agencies advertise excursions to ethnic minority regions in Yunnan and other parts of China using colorful photos of women in traditional clothing, emphasizing the people’s singing, dancing, and handicrafts.

This is also not a new phenomenon. Mo’s book examines how representation of non-Han people in Republican-era print culture often emphasized frontier regions’ unusual, colorful, and sensual attractions. This production of knowledge about frontier regions helped bind those areas to the center while also implicitly reinforcing the idea that the nation would come to be defined by Han sensibilities.

Traveling to new places is a magical experience, but it is not a politically inert act. Whether it’s Anthony Bourdain eating pig anus in Africa, or ordinary travelers looking for that perfect selfie to put on Instagram or WeChat, how people travel, where they go, and how they interact, interpret, and represent what they have seen shape and reinforce perceptions of those places. Mo’s book carries a reminder of the powerful influence travel has on our world, and the people we leave behind when we pack our suitcases and head back home.

On the Road in Republican China is a story from our issue, “Sports for All.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.